This review appeared in Standpoint in December/January 2016/17

John Stubbs, Jonathan Swift: The Reluctant Rebel (Penguin/Viking, 2016), 716 pp., £25

‘Swift was obsessed by shit’, opined my best friend in his undergraduate essay on the Dean. ‘So, it seems, are you’, shot back our supervisor in his marginal annotation. Dr. Colin Burrow, who echoed Swift in his wit and directness, would later supervise Stubbs’s doctoral work. But although Stubbs would likewise dismiss the view of Swift as shit-obsessed, he is not one of those authors drawn to write about those whom he resembles (unlike, say, John Carey, who like Stubbs has written on Donne).

From his base in Slovenia, where he is also a school-teacher, copy-editor and translator, Stubbs has produced a magisterial biography which is strikingly unlike its subject: consistently moderate, undemonstrative, even-tempered, open-minded, and tactful. Not that he presents his subject as the opposite of all these things; that would not be moderate or open-minded of him. He is sufficiently responsive to the disparate moral claims of Irish peasants, women, and Swift himself, to calibrate precisely how far the latter was responsive to the formers’ interests, and to state his findings without moralism: ‘Like most if not all of us, Swift’s personality was surely made up of many parts. One of these parts sympathised with the victims of his society; another concealed pain and insecurities in the language and attitudes of an oppressor.’ The book is laden with controversy – between Catholics and Protestants, Anglicans and Dissenters, English and Irish, Whigs and Tories – but if there is anything controversial in its presentation of Swift’s positions on these matters, a reader would not know it from its tone. If it appears fractionally more sympathetic to the High Anglican Tory position than any other, it feels that this is only because it must focus on Swift.

Despite Stubbs’s disciplinary background, the biography is far more historical than literary. There are no extended passages of criticism; he does not rip Swift’s works out of the history into which they are stitched. As a result, individual works are discussed briefly and repeatedly, whenever they become relevant to the history being described (in what – after an introduction starting in media res in 1710 – is a broadly chronological book). Yet Stubbs’s style also reveals a literary flair for compression: A Tale of a Tub ‘shocked all who weren’t entirely confused by it’; Swift ‘bonded with personalities that recognised and in their own ways equaled his unusualness as a person’; ‘There is much innuendo in the Swift-Vanessa letters, but innuendo rarely refers to a consummated urge’; and, concerning the ‘freedom’ that Swift professed to champion: ‘Freedom is only meaningful in a world of restricted options. The strict limits Swift himself abided by were the preconditions of his audacity in literature and politics.’ If Augustan poetry can be prolix, it can also be felicitously compressed. This may have rubbed off on Stubbs.

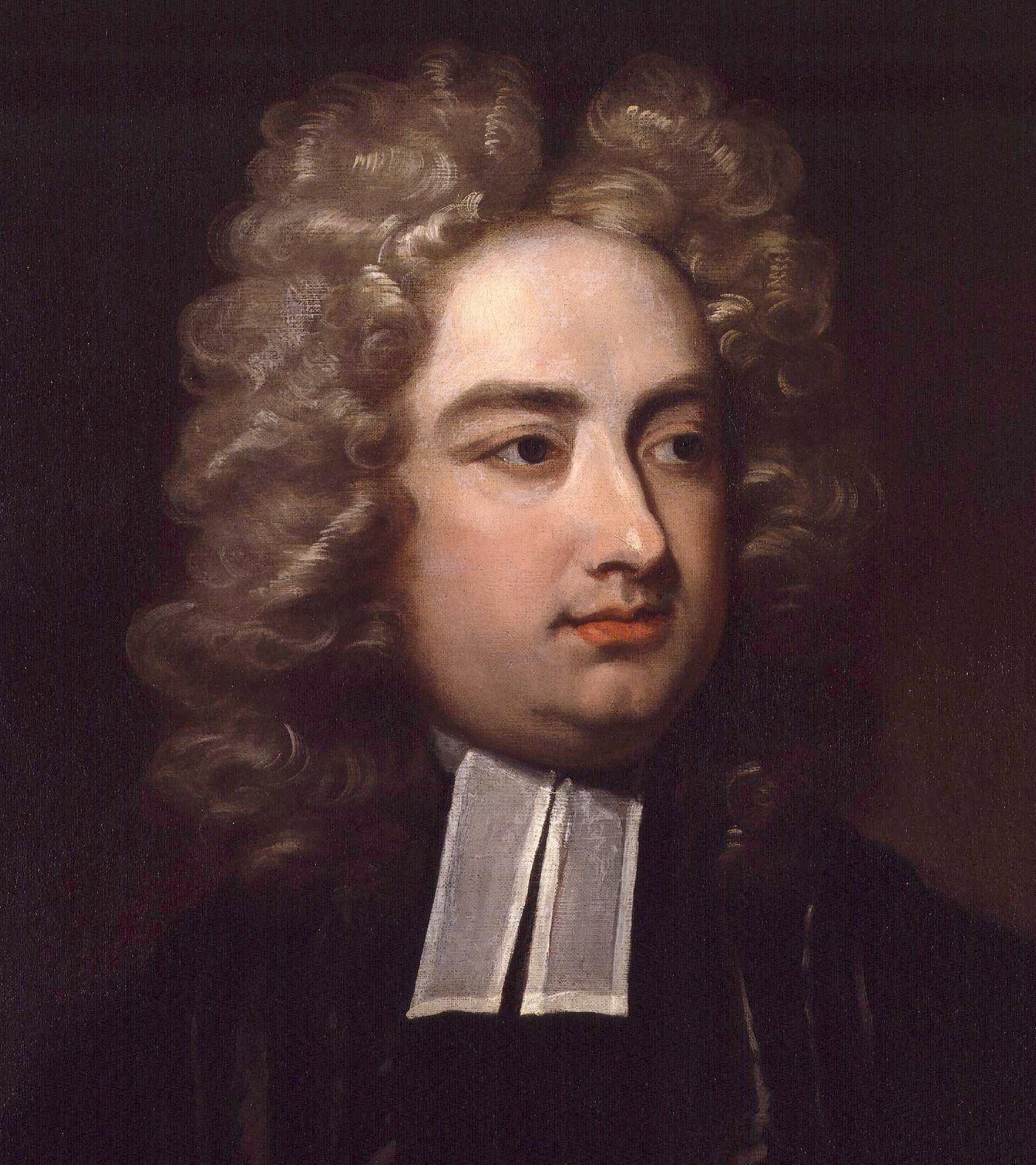

Stubbs also has a taste for architecture, and has clearly visited many of the places that Swift knew. ‘The Regal interiors Gulliver visits […] are never described at length’ is the observation of someone who would have made such a description, had he been Gulliver. Being a historicist biographer, he also tries to give a sense of what St. Patrick’s Cathedral, or its Deanery, or a London coffee house, would have looked, felt, sounded and smelt like in Swift’s own time. He not only describes the portrait made by the young Charles Jervas of Swift, but what the room in which Swift’s sittings took place must have looked like.

Broadly speaking, Stubbs defends Swift from charges both contemporary (of Jacobitism and irreverence) and subsequent (of misanthropy and madness). He reminds us that Swift’s reputation sank, fast from a peak of popularity, after his death – and was kept down by subsequent comments from W.M. Thackeray, D.H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley and George Orwell. He argues convincingly not only that Swift’s High Anglicanism wavered towards neither Catholicism nor Dissent, but that his promotion to the Deanery of St. Patrick’s (and no higher) was retarded in part precisely by his loyalty, whereas the loyalty of others was bought by their faster promotion. He dispels the image of Swift as a loner with detailed accounts of his friendships, for example with Sheridan. He stresses Swift’s aptitude as a scholar of Greek and Latin at his school and University, rather than the fractiousness that earned him a BA ‘by special grace’. On the vexed question of whether he ever had affairs or married, Stubbs concludes that he never married, probably never had an affair, and if he did it was more likely with Esther Vanhomrigh than with his greater soul-mate Esther Johnson. He rebuts the theory that he was asexual, and highlights Swift’s own comment that he would be very hard to please in the matter of a wife.

On the question of Swift’s alleged misogyny, Stubbs is clear that he was often misogynistic in the abstract, but not the concrete. His relationship with Esther Johnson showed that he sought in a woman an intellectual equal. He was a good son, movingly grieving for his mother in what may well serve as a cut-out-and-keep-quote for use at funerals: ‘I have now lost my barrier between me and death; God grant I may live to be as well prepared for it, as I confidently believe her to have been! If the way to heaven be through piety, truth, justice, and the charity, she is there.’ Swift proved himself to be ahead of his time on the question of rape, arguing about a rape trial in 1711 that: ‘Tis true, the fellow had a lain with her a hundred times before; but what care I for that?’ Stubbs argues, less convincingly, that in Swift’s poems evincing disgust at ageing females’ toilette, he is in part satirising men’s willingness to accept female deception for the sake of their own sexual gratification. If true, this opens up a further set of questions as to whether ‘making the best of oneself’ – albeit using the grimly lead-compounded methods of the age – is deception; as to what is more deceitful about an older than a younger woman’s toilette, given the period’s anti-natural fashions; and as to what on earth is wrong with lust for older women, be they deceivers or otherwise.

On the question of whether Swift was a Conservative or a rebel, part of Stubbs’s thesis is summed up by his subtitle ‘The Reluctant Rebel’. He was, Stubbs argues, instinctively conformist, but driven to protest by what he perceived as the outrageous behaviour of – for example – the English towards the Irish, and the Whigs towards the fabric of society itself. But he goes beyond, and somewhat contradicts, this thesis with his idea of Swift’s split personality: ‘At one and the same time he was a stern authoritarian and a daring cultural bandit. Managing as he could the torsion these tendencies created would make up a large part of the business of his life’. Stubbs adds ‘a marauding unholy ghost’ to make up his trinity: his attacks of what is now thought to be Ménière’s Disease, which combines tinnitus and vertigo, and which Swift endured with spirit.

Stubbs draws tellingly on Swift’s scholastic education, which had taught him to argue on both sides of a question. If he later satirised this practice, it at least gave him the training to inhabit a different persona on which his satire so heavily drew. The Puritan children’s literature with which he would have had contact as a child left its imprint on his ethics, and gave him a model for both his sincere, and his faux, didacticism. Taking us as far back as Swift’s grandparents’ generation, Stubbs shows him to be the product of the High Church on his paternal side, and Dissent on his maternal side. Although his conscious allegiance was to the former, his moral rigour, and insistence on physical and mental cleanliness, bears the impression of the latter.

The book does well at clarifying the desperately convoluted politics of the period, in which Irish Protestants found themselves split between supporting the Catholic Confederacy for the sake of their monarchism, and supporting regicides for the sake of their Protestantism; in which the pre-Reformation English in Ireland were split between loyalty to their original country, and to their religion; in which Swift’s maternal grandfather moved to Ireland because Dissenters were more tolerated there than in England; and in which the Scots sacrificed their Parliament for the sake of union with England, whereas the Irish, who retained their Parliament, found that they now had fewer privileges than the Scots. There is madness in this method, which Swift, with his intuitive understanding of madness, was well placed to point out – thus revealing how supposed lunacy might show greater sanity and humanity than Philistine propriety.

Stubbs is rightly concerned to gives a sense of the roughness of the time in which Swift lived. I was reminded of Barry Hines’s A Kestrel for a Knave, which the back cover of its Penguin edition describes as: ‘as real as a slap in the face to those who think that orange juice and comprehensive schools have taken the meanness out of life in the raw working towns’. This biography is as real as a slap in the face to those who think that the Glorious Revolution and coffee houses took the violence out of life in eighteenth-century England. ‘Late, very late, correctness grew our care/ When the tired nation breathed from civil war’ claimed Pope. But by the mid-1730s, when he wrote this, we still had some way to go. When Anne died and the Whigs gained the ascendancy under George I, Tories might expect to loose their liberty or even their lives. For a while Swift lived in fear of the Mohacks, a marauding band of young Whig aristocrats who terrorised London’s Tories, cutting off noses, ears and fingers. Swift diffused a bomb, which was sent to the Lord Chancellor, and was forced off the road by Whig hoodlums outside Dublin. Britain’s most spectacularly tortuous form of execution, hanging, drawing and quartering, was applied throughout Swift’s lifetime.

Yet Swift, and therefore this book, are also relevant to the present – as my iPhone’s auto-correction of the adjective ‘Brobdingnagian’ suggests. Twenty-first century Britain feels its connection to Swift more than to most other people of his century – albeit not to those aspects of Swift which Stubbs chooses to stress. He predicted the end of Anglicanism as the established Church in Ireland, and, if anything, would be surprised to hear that at the futuristic date of 2016 his beloved Anglican Church, and its state, remain united. He anticipated modern discontents with what is now known as crony capitalism, and his sympathies would have been with the Occupy Movement, if not with the presence of tents on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral. He would have supported, at least to a degree, the anti-consumerist movement, anti-makeup feminism, and animal rights. He was ahead of his time in personal hygiene (he changed his underwear daily), but also anticipated his fellow Dubliner James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence, and Sigmund Freud, in his explicit acknowledgment of bodily functions. Perhaps where he differs most from that majority of people today, who would not in fact have been happier had they lived in the eighteenth century, is in his veneration for those ideals which reality does not match. In his falsification of Augustan idealism lies: ‘a large part of his lasting appeal to a more modern readership that accept decay, mess and sometimes downright chaos as all but unavoidable – and in some cases a source of vibrancy and excitement. This is not to say, either, that Swift would not have preferred the Augustan version to be true. He very clearly would.’