This review was published in ‘The D.H. Lawrence Newsletter’ no. 89, Spring/Summer 2011, 12-18, and is made available here with the kind permission of the editor, David Brock.

Lawrence’s ‘Women in Love’ on the Small Screen

Summary

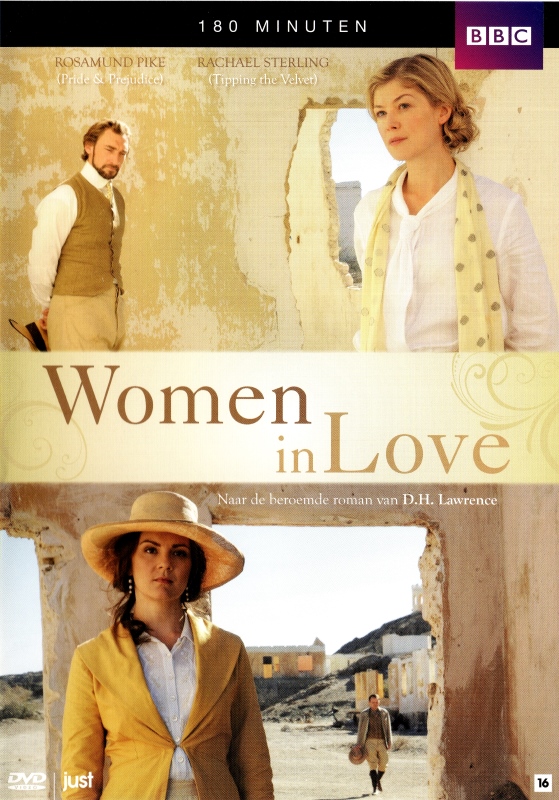

BBC4, March 2011, two episodes of 90 minutes, written by William Ivory, directed by Miranda Bowen: Rory Kinnear (Rupert), Joseph Mawle (Gerald), Rosamund Pike (Gudrun), Rachael Stirling (Ursula)

This adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s The Rainbow and Women in Love aimed at deep rather than superficial fidelity to the novels, and only very partially succeeded; this is not the startling work of expressionist cinema which Lawrence’s works (despite his own hostility to the cinema) one day deserve.

BBC4, March 2011, two episodes of 90 minutes, written by William Ivory, directed by Miranda Bowen: Rory Kinnear (Rupert), Joseph Mawle (Gerald), Rosamund Pike (Gudrun), Rachael Stirling (Ursula). Pages references below are to the 1987 Cambridge University Press edition of Women in Love edited by David Farmer, John Worthen, and Lindeth Vasey.

In terms of superficial fidelity to its original, the ambitions of the recent Ivory/Bowen television adaptation of Women in Love (and parts of The Trespasser and the second and third generations of The Rainbow) were limited. It gave to Gudrun a married lover and a holiday to the Isle of Wight, to Gerald a lover amongst his servants and a death in the South African desert, and to Birkin an actress-cousin resembling the Pussum and an early interest in defending God from Darwin. Its ambitions with regard to profound connection to the novels were greater, and that it fulfilled them to any degree was impressive, given the difficulties of adapting this of all novels. Its title and Lawrence’s British reputation create inappropriate expectations in audiences; it repeatedly proffers and subverts an impression of social and psychological realism; its speeches are long; its ideas hard to grasp; its ideals hard to accept.

Yet not everything was working against Ivory and Bowen. Women in Love is, for example, episodic – dominated not by description but by scenes between characters who are already known to the reader and who rearrange themselves frictionlessly and without important leaps in time or space (before the ending). Transitions are unobtrusively effected by narrative ellipsis (‘For a week or two he was ill’, p. 108) or by chapter endings; in film every change of shot gives the opportunity for a paratactic change of scene. By the same token, it offers the temptations of montage – and this is one to which many adaptations of novels yield when they impose sharper, more obviously meaningful scene transitions on their originals. The Ivory/Bowen adaptation does so on occasion. Whereas Women in Love rarely uses adjacent scenes to juxtapose, let alone liken or contrast, individuals, the women and the men, or the two couples, there is a section towards the end of the adaptation’s first episode in which Birkin is rejected and abused by a potential male lover on a train; this is immediately followed by Gerald having joyless sex with a servant, Gudrun crying after being denounced in public by her former lover’s wife, and Mr Crich dying slowly, terribly slowly. Noone is getting it right; they are all in it together, simultaneously getting something wrong – but only the viewers can see this. This is a privileged perspective of sympathetic but slightly ironic overview which the reader never possesses in the novel; its scenes are long, the meanings which inhere in their juxtapositions often minor or obscure, and the reader is as unsure as any of the characters as to what, in this world, constitutes good or bad living.

Such a modification of the novel’s modes was avoidable. With regard to depictions of nakedness, however, Women in Love presents peculiar problems to adapters. Of course, words can be as arousing as images: in an invented scene of the film in which Hermione taunts Birkin with his failure to get an erection, then purports to see a slight tumescence, she cries: ‘See! I knew you’d need words!’ (in the context of Lawrence’s own reaching towards and distrust of words, this is a plangent observation). However, the real sight of naked strangers retains a distinct power to arrest the attention of anyone to whom such sights are not common; this power is at its lowest in nudist colonies or porn films, where it is expected, but far higher in costume dramas, with their connotations of literariness, history, and therefore of sexual inhibition: the costumes in such dramas are meant to be kept on. For this reason, although nudity and sexual activity are commonplace in mainstream films, a scene in which Colin Firth as Mr Darcy in the 1995 BBC Pride and Prejudice (dir. Simon Langton) renders his nipples slightly visible through his shirt by swimming in a lake has become one of the most famous scenes in British television history. Ken Russell’s 1969 Women in Love is still remembered principally for its scenes of nude wrestling between Oliver Reed and Alan Bates, and of Glenda Jackson naked. Critics of the latest adaptation have made much of the amount of nudity which it contains: on my count there are four sex scenes, three bathing scenes, and one wrestling scene, constituting in total only a small fraction of the running time. Of course, the reaction to nudity is far stronger in Lawrence’s and the BBC’s home country than in that of Frieda, which also generates Gudrun’s and Ursula’s names. German audiences of the recent adaptation would be unlikely to remark on the scene in which Rosamund Pike and Rachael Stirling swim naked at the water party for the simple reason that, had the party been held in Germany, they would probably not have been the only ones. The problem is that this scene in the novel is not meant to produce embarrassment or titillation in its readers, as its filming does to an English audience even now. Moreover, I think it highly probable that Lawrence would have disapproved of audiences watching naked actors, would have classified their acceptance of money in order to appear naked as literal and metaphorical prostitution, and would have classified the interaction between them and an absent film audience as an ersatz connection bearing a similar relationship to real physical encounter as First World War warfare to hand-to-hand combat. Of course, he presented naked bodies abundantly to the eye in his paintings, but these remain firmly within the artistic sphere of the imitative, as the nudity of an actor does not. Moreover, in Women in Love bodies are rarely seen naked, and when they are they are seen neither in detail nor (with the exception of Birkin in the undergrowth) in sexual situations; that is, Gerald diving, Gudrun and Ursula swimming, and Gerald and Birkin wrestling. During one of the novel’s most important sexual scenes, we see only that Gerald ‘pulled off his jacket, pulled loose his black tie, and was unfastening his studs’, and know that Gudrun is wearing a night dress (p. 344). During the rapture of Birkin and Ursula in the inn at Southwell, they are both fully clothed; Ursula ‘traced with her hands the line of his loins and thighs, at the back, and a living fire ran through her, from him, darkly’ (p. 313). Critical uncertainty over the precise part of the male body denoted by Lawrence’s loins is apt, since they are as much a psychological as a physiological concept. There is no equivalent scene in the adaptation to this scene in the inn – not surprisingly. The fact that the novel’s most successful sexual connection in the novel takes place in a fully-clothed encounter indicates its determination to reach beyond conventional sexuality. As Birkin tells Ursula: ‘I don’t want to see you […] I want a woman I don’t see’ (p. 147); in this novel sex is not in the eye but the soul (or, a sceptic might want to say, as Birkin does of Hermione, the ‘head’: p. 41). The result is that with the adaptation’s excision of the novel’s narrative voice – which plays its most important roles in such scenes – much of their meaning is lost.

What the adaptation unfortunately does show is precisely conventional sexuality. In only one scene is sex shown as spiritually destructive: after Anton knocks Ursula down on a beach after she breaks with him he bends to her, kisses her, and has sex with her. But this is merely exploitative, angry, common-or-garden near-rape. The adaptation does not, during Gerald and Gudrun’s first sex, attempt to render the impression that ‘Into her he poured all his pent-up darkness and corrosive death’ (p. 344); indeed, the experience is presented as positive for both partners. Rather, it uses the conventional Hollywood cinematic language of sexuality, which misleadingly pretends to realism but is in fact euphemistically graceful. We see Gudrun and Gerald naked facing one another, with Gerald not even partially erect. Their naked bodies are probably more than Lawrence would want us to see, but if we are to see them, we cannot attribute the absence of an erection to artistic licence, but to a lack of licence in English television: why, then, show the nudity in the first place? The adaptation reproduces a number of clichés of film-sex: unrealistically brief fumbling with Edwardian clothes before penetration (Anton and Ursula), the near-painless loss of virginity (Ursula), and painless withdrawal. Also lacking in credibility, but more significantly, is Gudrun’s affair with her married art master. No matter that Gudrun is reinterpreted as a Bohemian libertine before her encounter with Gerald; such a character is unlikely to be attracted to a physically unprepossessing, nervous man who gets past his nervousness on occasions to deliver improbably profound lines. Women in Love is not a realist novel, but none of the sexual or spiritual attraction presented within it is similarly unlikely. Sex in the adaptation is best shown when least shown: the shot of the back of Gerald’s car rocking as he bounces one of his servants up and down on his cock brilliantly captures the impersonal, mechanical, slightly absurd nature of the congress. The mutual arousal of Gerald and the passive-predatory Pussum might easily have been translated to film, but the arousal, of which we see much in the novel, is replaced by the congress, of which we see nothing – and the uncultured Pussum is replaced by an educated actress-cousin of Birkin’s, in order to swell from three to four the number of the film’s eloquent, sexually-demanding women, and thereby to reinforce its feminist perspective. The adaptation’s best representation of nakedness is that of Gerald and Birkin’s wrestling. The shift from the fireside of the novel to a beach was felicitous: it rhymed with the location of Ursula’s near-rape and the sand of Gerald’s death, and turned the waves, land, and sea into metaphors of liminality, danger, nature, and infinitude, as they fight in earnest over Birkin’s claim that Gerald knows only lust, not love. This scene is long enough for the effect of the actors’ nakedness to wear off on the audience, and leave the impression of two bare, forked animals on the vastness of sea and earth, disputing the extent to which they are anything more than animal.

Here landscape is used to symbolic effect, as it is also when Gerald dies in the desert. In general, however, the adaptation clings to the surface naturalism which only intermittently and ambiguously characterizes the novel itself. That is, the former falls convincingly within the tradition of meticulously-historicist, English costume dramas, despite the restraints of filming throughout in South Africa. Naturally, the costumes, which are so important to this novel, are well attended to. At one point Gudrun appears even more radically dressed than in the novel, in shirt, tie, gilet, and trousers. But this dress is merely given to her as a metonymic indication of her character; it is not dwelt upon, as in the novel, in a manner which exceeds the bounds of naturalism and becomes expressionism. The novel, however, was written during a high point of expressionism in visual art, and on the threshold of its introduction to cinema. Arguably what the novel needs is treatment by the modes of the latter. In the novel, for example, a rabbit is let out of its cage – and all hell is let loose. In the adaptation, it merely inflicts some deep scratches; F.W. Murnau or Luis Buñuel would have rendered this to the sound of screaming strings, with extreme close-ups on the eyes of the rabbit, of the man, of the woman, on the wounds, on the trails of blood, the sky, the muscles peddling the air, the bloodied grass – and finally, an abrupt change of mode, and Bismarck nibbling the lawn.

One scene in the adaptation has this kind of mesmeric quality, and it is not taken from any of the novels. Hermione and Birkin are in her bedroom; she is dressed more in jewels than clothes; he is in just a shirt; the room is white with sun; and she accuses and mocks him like a malevolent goddess. That is, she is transformed from the hypersensitive, patronizing, eccentric, cultured, desperate woman of the novel, into a sexy, evil persecutor. What this scene achieves is to unite speech with spiritual oppression, as the novel – which is after all unified through its single medium of words – does not. In the novel people say things which hurt and anger one another, but inflict their profoundest harm in other ways, such as destructive sex (Gerald with Gudrun), bullying a horse (Gerald with both sisters), or absence (Birkin to Hermione in the church). This scene in the adaptation combines speech with expressionist camerawork in a manner which conveys the profundity of influence of one person over another as none of the other scenes do. Yet it is a flashback, interposed to explain Birkin’s hasty departure when Hermione arrives unexpectedly at Shortlands. As such, the hallucinogenic quality of her behaviour is attributable to the distortions effected by Birkin’s memory and vulnerability to her attack, rather than the truth to two people of their interaction in real time. The profundity of the connection between Ursula and Birkin might, for example, have been conveyed through scenes as dreamlike as the other is nightmarish. Even Russell, whose gift for expressionism is apparent in his adaptation of a work by Lawrence’s last best friend, Aldous Huxley (The Devils, 1971), had failed to apply this gift to Women in Love two years earlier. Indeed, such a translation to a visual medium would not always require much manipulation of the surface of the action: the strangeness of Birkin’s experience with the vegetation would have survived a fairly straightforward representation. The novel attributes great spiritual importance to animals – rabbits, cats, dogs, horses – which could have been retained through the temporary concentration on them by the camera, from unusual angles, at the temporary expense of plot. Some of the novel’s meaningful details are altered without reason. Hermione biffs Birkin with a lapis lazuli paperweight not only because Lady Ottoline Morrell once gave Lawrence such an object, and because it is the kind of gorgeous, expensive, Oriental object which characterizes her, and because it is stone, and as such metonymic and metaphoric of the physical world, which almost kills Birkin physiologically but cannot permanently injure him spiritually. In the adaptation it is replaced by a brass bell-like ornament, without any apparent meaning. Finally, cinematic expressionism relies heavily on music, and the music accompanying this adaptation might have been far more modernist – contemporary with the novel itself – and discordant – consistent with much of its spiritual action – than the unremarkable piano music which connected this adaptation to many another adaptations of novels vastly different to Lawrence’s. The most noteworthy use of music was Bach’s Well-Tempered Klavier as Gerald walks into the desert and dies: this represented the connection with human civilization, empathy, patience, Christianity, and the ‘eternal creative mystery’ which Gerald is beyond the reach of, and therefore dies utterly (p. 478).

In the adaptation, as in the novel, Birkin appears as a sequence of shifting propositions – what the Contessa calls ‘a changer’ (p. 92) – but whereas in the latter he is confident in each in turn, in the adaptation he is exposed as grasping towards truth, and as far more aware of his own contradictions (these shifts are also more apparent because they occur over ninety minutes rather than five hundred pages). The result is that he is less likely to offend viewers, but at the expense of becoming a somewhat pathetic figure. His body is not consumed by spiritual intensity and consumption, but made inadequate by indecision and podginess. That is, his character and his body correspond – at which point it may be noted that a somewhat overweight actor can today be accepted as a male lead, whereas the equivalent would not be true of an actress: both Stirling and Pike are lean. However, it is Hermione and the Pussum who are described as ‘slender’ – not a positive feminine quality for Lawrence throughout his oeuvre – and although this is not specified, it is likely that Ursula and the ‘soft-skinned, soft-limbed’ (p. 8) Gudrun are fuller than the actresses who play them.

Like many critical interpretations of the novel, the adaptation differentiates the central characters more sharply than the novel. In his review of Women in Love John Middleton Murry complained that to Lawrence the central characters are apparently ‘utterly and profoundly different; to us they are all the same […] We should have thought that we should be able to distinguish between male and female, at least. But no! Remove the names, remove the sedulous catalogues of unnecessary clothing – a new element and a significant one, this, in our author’s work – and man and woman are indistinguishable as octopods in an aquarium tank’ (Colin Clarke, D.H. Lawrence: ‘The Rainbow’ and ‘Women in Love’, London: MacMillan, 1969, pp. 68, 70) Similarly, a Miss Macaulay, in her review for the Westminster Gazette of 2 July 1921, found ‘Ursula and Gudrun […] as indistinguishable in character and conversation as they are in their amours and their clothing’ (Women in Love, p. liii). Many subsequent critics have exaggerated the differences between the sisters, the men, and the couples, in order to make sense of, and justify, the deviation of their fates; Russell’s and Bowen’s adaptations do likewise. In the latter Birkin, for example, has the repressed heterosexuality which he lost in a discarded draft of the novel (see the ‘Prologue’ chapter, Women in Love pp. 489-506). Gudrun is turned into a somewhat cold Bohemian, and Ursula into a conservative who rebukes her for her long stays away from home: at times they come close to resembling the Sophia and Constance Baines of Arnold Bennett’s The Old Wives’ Tale (1908). London’s Bohemia is more explicitly debauched than in the novel, being represented by a large, lavish bar-lounge in which couples kiss openly. Of course, the social differences between the Pompadour and the classroom at Willey Green or the dining room at Shortlands are great – but Lawrence is not greatly interested in them. Women in Love is far less concerned with social differences in England than with the Arctic-African axis of humanity as a whole, and is not sufficiently interested in Bohemia to depict it as long or as negatively as does the adaptation. The latter introduces a class dimension to the Schuhplattern in the inn, since the girl with whom Gerald dances becomes the daughter of one of the greatest families in Bavaria, and Gudrun feels threatened by her. In any case, the adaptation’s attempts to stress class are limited by shooting in South Africa; there are few outside shots of Shortlands or Breadalby, for example, to help establish Gerald’s and Hermione’s wealth; Beldover is never seen by day dark with coal dust.

On the other hand, some of the differentials around which the novel is orientated are softened or even reversed in the adaptation. Although in the novel Birkin at times affects a superficial conventionality, that of Gerald is more consistent and profound, and it is Birkin who is Gerald’s guide in Bohemia. In the adaptation it is Birkin who appears conventional whereas Gerald resembles a highly-sexed Christ; it is the latter who wears a beard (although this carries the benefit that his meaninglessness is emphasised: he is a Christ-like figure without a mission or faith). Gudrun is made colder but less malicious than in the novel – she never tries to crush Gerald, even towards the end, and after his death mourns him and claims to have loved him, making their relationship ultimately less different to that of Birkin and Ursula than in the novel. It is Ursula who dances naked, but Gudrun who chases the cattle – whereas in the novel both actions belong to Gudrun. Most importantly, the differences of mode between The Rainbow and Women in Love are effaced. At first thought, adapting parts of both novels in two episodes makes some sense; the two novels were originally conceived under one title. However, much of the material of Women in Love appears in the first as well as the second episode, and both episodes use the same cinematic modes. As has often been noted, the third generation of The Rainbow introduces a shift towards modernity which Women in Love completes, at the expense of flattening Will and Anna Brangwen into charicature. That is, Lawrence does not take Will and Anna’s relationship, and those of Ursula and Gudrun, seriously at the same time. Unlike The Rainbow, Women in Love is not a generational story – it exists in a fixed and ahistoric present. Admittedly, Gerald’s parents are serious characters – especially the father. The adaptation does not develop his character, but his obsolescent Christianity is attributed to Birkin, whom we witness in the process of abandoning it. The First World War, which did indeed have some effect on the shift of mode between the two novels which Lawrence wrote over its course, is acknowledged as a historical fact by the adaptation – both Gerald and Birkin fight in it at the beginning of the second episode. But it is a false dividing point; these characters are not obviously altered by the experience, and nor is the adaptation’s mode of presentation.

The novel’s most emphasized polarity – between the African and the Artic – is lost. Rather there is only Africa – and that with a less profound presence than in Women in Love. In a brief glimpse of Gudrun’s art exhibition we see paintings of naked figures (like Lawrence’s), and African-style sculptures (like Halliday’s Fetish). Gerald, who is brown-haired rather than blonde, buys a mine in South Africa, and takes his lover and two friends with him there on holiday (now the shooting location can finally reveal itself). Having Gerald die in the desert, however, does not merely reverse his association with the Arctic. He does not die a death ‘controlled by the burning death-abstraction of the Sahara, […] fulfilled in sun-destruction, the putrescent mystery of sun-rays’ (p. 254); Africa is not presented as disintegratively sensual. Nor, on the other hand – despite their shared undulating emptiness – does the desert signify the ‘ice-destructive knowledge, snow-abstract annihilation’ (p. 254) of Lawrence’s Tyrol. It is closer to representing the ‘vacancy’ which Shelley hypothetically attributes to Mont Blanc at the end of his poem of that name; it is simply that – a desert. It is therefore appropriate that the adaptation gives its last words to Gerald: ‘I want to go to sleep’.

Overall, however, the adaptation is far less disturbing, and less strange, than the novel. Its incorporation of elements of The Rainbow and The Trespasser only exacerbates this. The adaptation is overwhelmingly concerned with the relationship between love and lust in a changing society; the novel is concerned with how humanity can survive and whether it deserves to. The disturbing elements are softened in several ways in addition to those already mentioned; Loerke is not a paedophilic bisexual sadist but a smooth-talker with a striking resemblance to Oliver Reed; Winifred is not detached and uncannily ironic, merely a hearty, unkempt child. And yet, from this adaptation we do take the sense that Women in Love is a profoundly serious work, by a serious author, which does not even purport to have solved the problems and questions that it raises. And for this it should be welcomed, even if it is not the startling work of avant-garde cinema which Lawrence’s writing one day deserves.