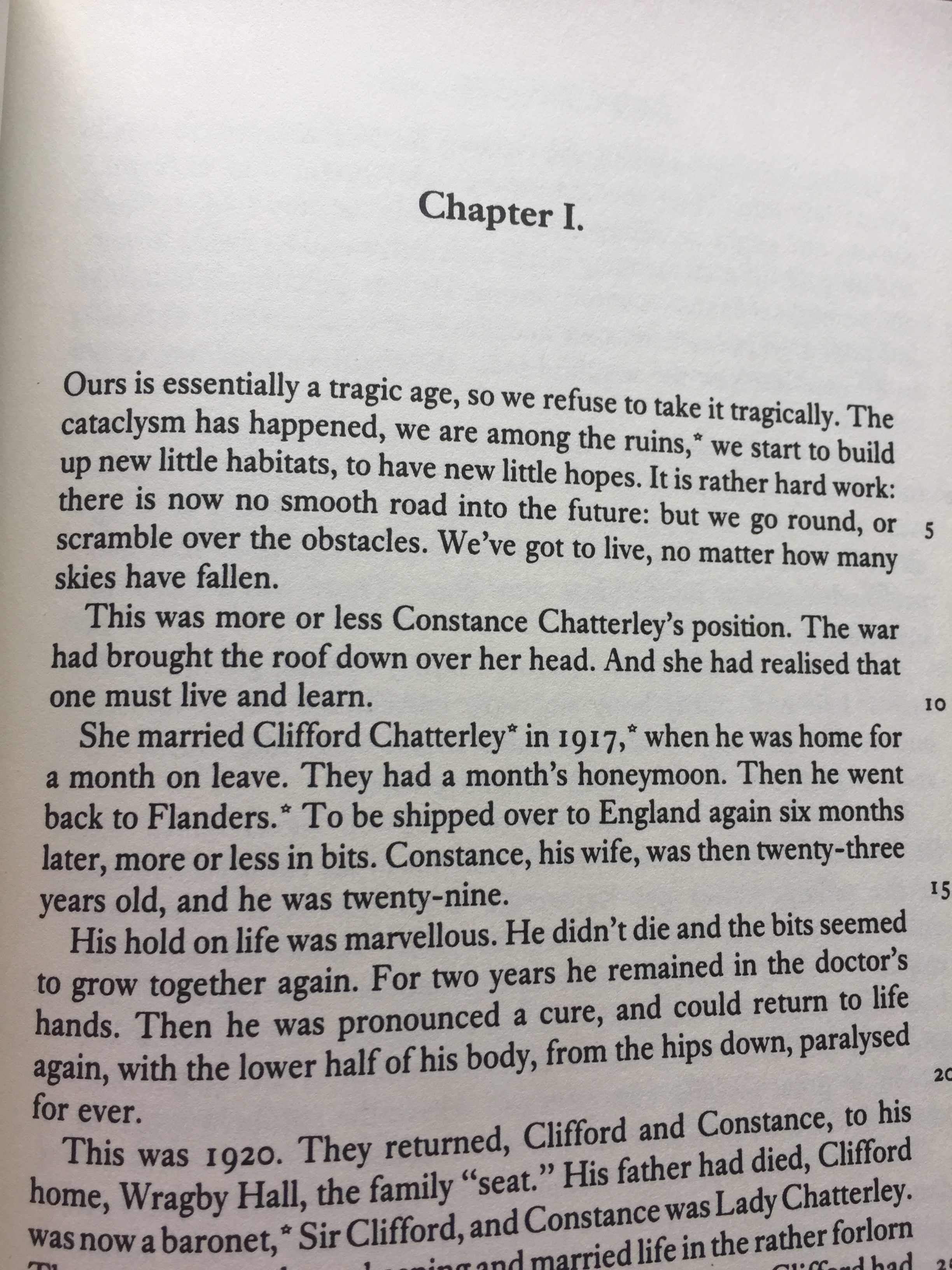

The opening of Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928)

This report was written for the D.H. Lawrence Society Newsletter, forthcoming Winter 2018/19. It appears here in pre-edited form.

International D.H. Lawrence Conference, Thursday 29th– Saturday 31stMarch 2018

University of Nanterre, Paris

Ginette Roy, who has been organising Anglophone international D.H. Lawrence Conferences at the University of Nanterre ever since the nineteen-eighties, issued the following Call for Papers for the thirty-second of these conferences:

RESISTING TRAGEDY

The theme of this conference has been prompted by the first line of Lady Chatterley’s Lover: ‘Ours is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically.’

The statement invites reflection on the literary means and devices that were adopted by Lawrence in order to resist tragedy, both here and elsewhere in his writings. The strategies of resistance include various arts of distanciation through which the tragic can be warded off. They can be linguistic, poetic, rhetorical, or can involve the interplay between a variety of perspectives, tonal shifts, humour, satire, romance, poetic licence, the refusal of seriousness etc.

The focus of the 2018 Conference should not be exclusively or too explicitly on WW1 and its consequences. If the opening to Lady Chatterley’s Lover offers an explicit reference to the war and, in the second sentence, an explanation of its origin and a hypothesis regarding the responses that it arouses, ‘the cataclysm has happened, we are among the ruins, we start to build up new little habitats, to have new little hopes’, the focus of the conference is to be less on the specific nature of the ‘cataclysms’ than on the nature and the substance of these ‘little habitats’ and ‘little hopes’ that are devised, conjured up, as if the immensity of ‘cataclysm’, apocalypse, were unable to put an end to an irrepressible individual and collective inventiveness. The resistance to tragedy thus appears to be the condition or cost exacted of a society or of a social agent who is to survive or outlive the ‘cataclysm’, a ‘cataclysm’ which is both historical, epochal, but also, perhaps, existential or anthropological. Lawrence asserts: ‘Tragedy looks to me like man/ in love with his own defeat’ (Pansies). We may then suggest further lines of reflection on the following themes: resistance or non-resistance to tragedy whether personal, social or political, heroism or escapism, the denunciation of Hamletizing, the temptation of oblivion, the refusal of sacrifice or self-annihilation, resilience and creative destruction. This list is of course not exhaustive.

Perennially a good topic, this – as perennial as tragedy, or at least as the modern debate about its perenniality, in which Lawrence himself was vigorously engaged. At times, like Nietzsche, Lawrence wrote positively about tragedy: ‘If it were a profound struggle for something that was coming to life in us, a struggle we were convinced would bring us to a new freedom, a new life, then it would be a creative activity in which death is a climax in the progression towards new being. And this is tragedy. […] If men are not more than implements, it is nontragic and merely disastrous’ (‘Preface’ to Touch and Go). At other times, and often more memorably, he writes about tragedy dismissively: ‘Tragedy looks to me like a man in love with his own defeat/ Which is only a sloppy way of being in love with oneself’ (‘Tragedy’ in Pansies).

This variability is not, or is not only, the result of Lawrence’s habitual flux and implied Whitmanesque stance of ‘Very well, then I contradict myself/ (I am large, I contain multitudes)’. Tragedy spoke to Lawrence sufficiently seriously, as a category which might be applied to both art and life, as to apply considerable thought to it, therefore and to typologise it. He first does this in The Study of Thomas Hardy, in which he cuts Hardy’s tragedies down to size as ‘lesser’, society-related tragedies in comparison to the the ‘greater’ ones, in which the largest morality is deliberately transgressed. He also identifies the ‘little’ tragedy of characters failing – as most of us do – to fulfil themselves. Such distinctions do much to alleviate the apparent contradictions between his statements about tragedy.

Accordingly, several of the twenty-four papers concerned themselves with Lawrence’s – and earlier authors’ – distinctions and definitions of tragedy. Marie Géraldine Rademacher read Sons and Lovers through the prism of Aristotle; Nick Ceramella noted Lawrence’s preference for Italian over German opera (‘Damn Wagner and his bellowings at fate and death’ – a flat contradiction of Nietzsche’s advocacy of modern, Nordic tragic opera over its lifelessly trivial and un-tragic Italian predecessor); Benjamin Bouche described Lawrence’s concern with ‘le tragique de banalité’ (recalling Gudrun’s description of Gerald’s as a ‘barren tragedy’); Masashi Asai traced how the word ‘tragedy’ (and ‘triumph’ and ‘oblivion’) changed its meaning throughout Lawrence’s last works; whilst Michael Bell concentrated on Nietzsche’s affirmation of tragedy-as-art over tragedy-as-life, in the context of the larger relationship between tragedy as a genre and as a world-view – a dichotomy which Lawrence less than most writers recognised, yet which was de facto a context for all our discussions.

Theorists of tragedy were not the only writers to be brought into relationship with Lawrence. Lawrence’s most immediate tragic predecessor, Thomas Hardy, was discussed by Fiona Fleming, who contrasted his pessimism to Lawrence’s responsive optimism. I made the same comparison and the same conclusion, in relation to both writers’ responses to Darwin. Sue Reid traced a line of resistance to tragedy running from Nietzsche, through Lawrence, to Anthony Burgess. Adam Parkes explored Lawrence and Huxley’s critical and satirical responses to each other’s utopian and dystopian visions, focusing particularly on ‘The Man Who Died’ and Eyeless in Gaza. Richard Kaye found parallels between the modes of resistance to tragedy of Lawrence and George Gissing. Michael Bell quoted Yeats’s poem ‘Lapis Lazuli’ – giving the adverb ‘by heart’ its full meaning – in order to exhibit its practical meditation on the relationship between art and life.

In accordance with this range, the Lawrencian texts studied went well beyond the obvious candidates for this topic: ‘The Ladybird’ (Margaret Storch), The Lost Girl (Richard Kaye), Touch and Go (Ayca Vurmay), Aaron’s Rod (Stewart Smith), ‘The Blind Man’ (Marina Ragachevskaya), Sea and Sardinia (Jane Costin), ‘New Heaven and Earth’ (Theresa Mae Thompson) and Studies in Classic American Literature(Claude Barbre, who opened his paper with an anecdote about meeting Robert Lowell – who had just escaped from his psychiatric institution – at the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum in 1976. He had, it seems, made these marbles a second home. He flapped his arms like wings running across the gallery to greet Barbre. Three months later, he died in the back of a New York taxi, his arms outstretched like wings. I confess that I didn’t quite follow the relevance of this anecdote to the discussion of Lawrence’s responses to the American sublime which followed – but it was the best conference-paper-opener I’ve experienced).

All of the contributors variously rose to Ginette Roy’s brief of writing about resistance to, or overcoming of, tragedy (which Michael Bell, with typical acuity, reminded us are two very different things). Several presenters used the term ‘tragicomedy’ in the sense of a situation that had seemed potentially tragic, but which is redeemed as a comedy. Thus Marina Ragachevskaya stressed the ultimate happiness of the eponymous protagonist of ‘The Blind Man’, and Richard Kaye argued that The Lost Girl(which starts: ‘However it be, it is a tragedy. Or perhaps it is not’) permits comedy to its protagonist by allowing her to enter a counter-cultural world. Gaskell and Gissing had done likewise before him, in refusing to allow a tragic fate to the old maids of Cranford and The Odd Women. Howard Booth adduced the phoenix, particularly in relation to violence (for example, Baxter and Paul’s fight in Sons and Lovers, which initiates intimacy between them). Stewart Smith mentioned the phoenix in his exploration of Aaron’s Rod’s awareness of the individual’s absolute expenditure in death, alongside its belief in individuals’ ability to create their own, new meaning.

Holly Laird likewise pursued the path of working through, rather than resisting or refusing, tragedy. She did this in relation to Ursula’s suicidal depression on Sunday morning in Women in Love– a novel by a degeneratively ill author, which envisions the world’s terminal illness, yet which also offers a path out of tragedy by means of meditative self-knowledge. This path is one which Hardy’s protagonists, according to Lawrence, tragically missed.

Other presenters focused on the connection between the comic and comedic, and adduced Lawrence’s rich sense of humour (exemplified by Jonathan Long in his survey of Lawrence’s letters, which exhibted wit even in the dark days of 1917), and how he used it to ward off the tragic (as in his writing of The Merry-Go-Round whilst his mother was dying, as Jane Costin argued). Marie-Géraldine focused on the intersection of the comic with the tragic at Mrs Morel’s death, as the children laugh at the suggestion of matricide; Elise Brault-Dreux also noted the comedic potential of morphine. Marie-Géraldine noted that Sons and Lovers’ ending is comedic, even though Mirian personally suffers a tragic ending; for Paul, self-love is the way out of tragedy. Ayca Vurmay explored Touch and Go’s thoroughly-mixed tragi-comedy, which ultimately tends towards Nietzschian life-affirmation in its presentation of the touch-and-go collision of labour and capital. Brigitte Macadré-Nguyên argued, in relation to non-tragic deaths in ‘The Fox’, The Rainbowand Women in Love that ‘the question is not so much resisting tragedy as coming to terms with it by approaching it with derision and macabre carnivalesque laughter, thus refusing to give it a “tragic” quality.’ Sue Reid argued that Nietzsche’s Ecce Homoprovided a model of anti-tragic self-satire which Lawrence had followed in Mr Noon,and Burgess in his Enderby Novels.

That the most comedy-orientated of the papers appeared in the conference’s last panel was fitting not just as a segue to the prosecco reception which followed, but with the fact that this was Easter Saturday, and that the phoenix was, indeed, about to rise. Earlier papers had been heard through Maundy Thursday and Good Friday – but we had come through.

I spent the few hours between the end of papers on the Friday, and the conference dinner, showing Ayca Vurmay of Mustafa Kemal University touristically around the Opéra and Galeries Lafayette. I learned that her university is in Hatay, close to the Syrian border, which therefore currently hosts many refugees. She is a Forsterian, which is why I had not seen her at a Lawrence conference before. I admired her fearlessness – not just in living as close to a war zone as she does with such apparent equanimity, but in travelling, alone, to a country she had never visited before, to be with scholars whom she had never met before. Lawrence would have made her the heroine of a short story.

For me, the conference was a comfort. I had had a personal blow just before setting off for Paris, and arrived with thoughts of tragedy pressing more-than-usually-strongly in my mind. Hence, staying up late over my paper on the night of Maundy Thursday, I decided to end it this way: ‘That is Women in Love the work of art, which contains particular emotional burdens, as our lives so often do. But in the very openness of the ending in an unresolved argument, the novel refuses to separate itself from life as a tragedy implying a tragic universe. There is a way out – if not for us then for others – out of the mountains, out of England, out the war, one might find it – indeed to believe this is to have found it – time has not ended, the game is never up.’

The conference was not just a celebration of Lawrence’s resistance to and transcendence of tragedy, but a comedy of friendship, and of the continuity of friendship. I felt this particularly at the conference dinner. Michael Bell recited his tribute to Ginette Roy, whose birthday it happened to be:

La femme qui a vécu

What can we say of her? Her name is King

Which rightly says authority. Yet is she woman

And mother to us all. In my country

The four great reigns were all of queens.

And so we find it here. Yet no monarchist she,

A soixante-huiter to the core:

All for the re public, the public thing,

The people’s good. Joined in this by Roger,

That amiable man, she was his

Pearl without price; Roger’s thesaurus,

So to speak. Call her priestess of Isis,

Honouring dark gods among the Cartesians

As academic concrete spreads

Her annual ritual finds la terre in Non-terre,

And tirelessly waters the seed.

So, as Lawrencian generations sprout,

I say, long may she rain.