Report of the Twenty-Seventh Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Maria Thanassa

Sardonic Paganism: D. H. Lawrence and the Figure of Pan

Friday 22nd November 2019

New College of the Humanities, 19 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3HH

6.30-8.30 pm

ATTENDERS

Catherine Brown

Jane Costin

Patricia Hopewell

Alex Korda

Dudley Nichols

Jane Nichols

Anthony Pacitto

Susan Reid

Lara Taylor

Maria Thanassa

Nahla Torbey

Aleksander Vasilkov

[Lawrence wrote the short story ‘The Last Laugh’ February-April 1924, the short story ‘The Overtone’ in April 1924, the essay ‘Pan in America’ May-June 1924, the novella St. Mawr in June-September 1924, and the novel The Plumed Serpent in 1923-5. During nearly all of the period in which he wrote these works he was living in New Mexico and Mexico; only briefly at the beginning and end was he in England and/or Italy. The first three of the works named above focus on Pan; in the last two Pan is not central but features significantly. In all of them he is presented positively – but variously, as Maria Thanassa explored.]

Maria started with an account of the history of her engagement with Lawrence. Initially enthusiastic whilst undertaking her undergraduate and postgraduate studies, she stopped reading him for some time after finding the destructive masculinity she encountered in The Plumed Serpent unsettling. Her interest in Lawrence was re-kindled during the last phase of her doctoral studies, and she has since given a number of presentations on Lawrence.

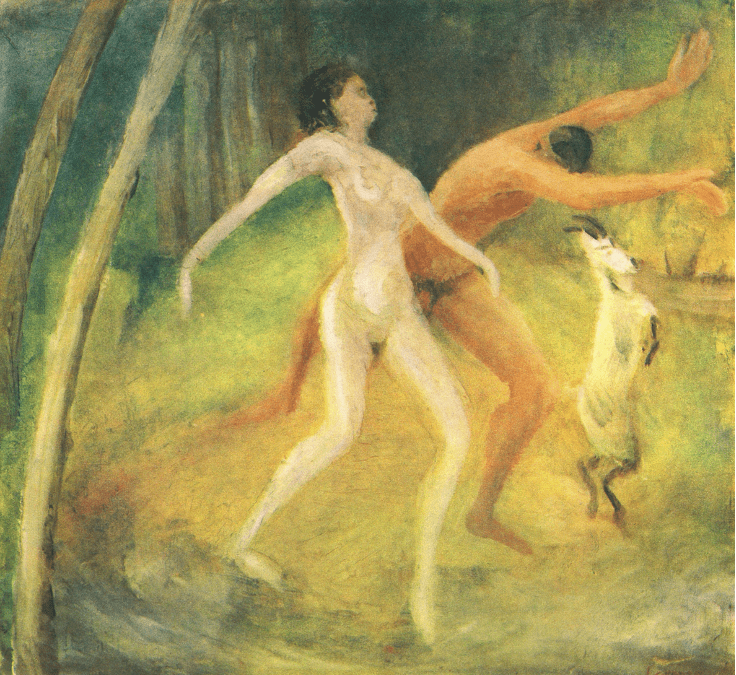

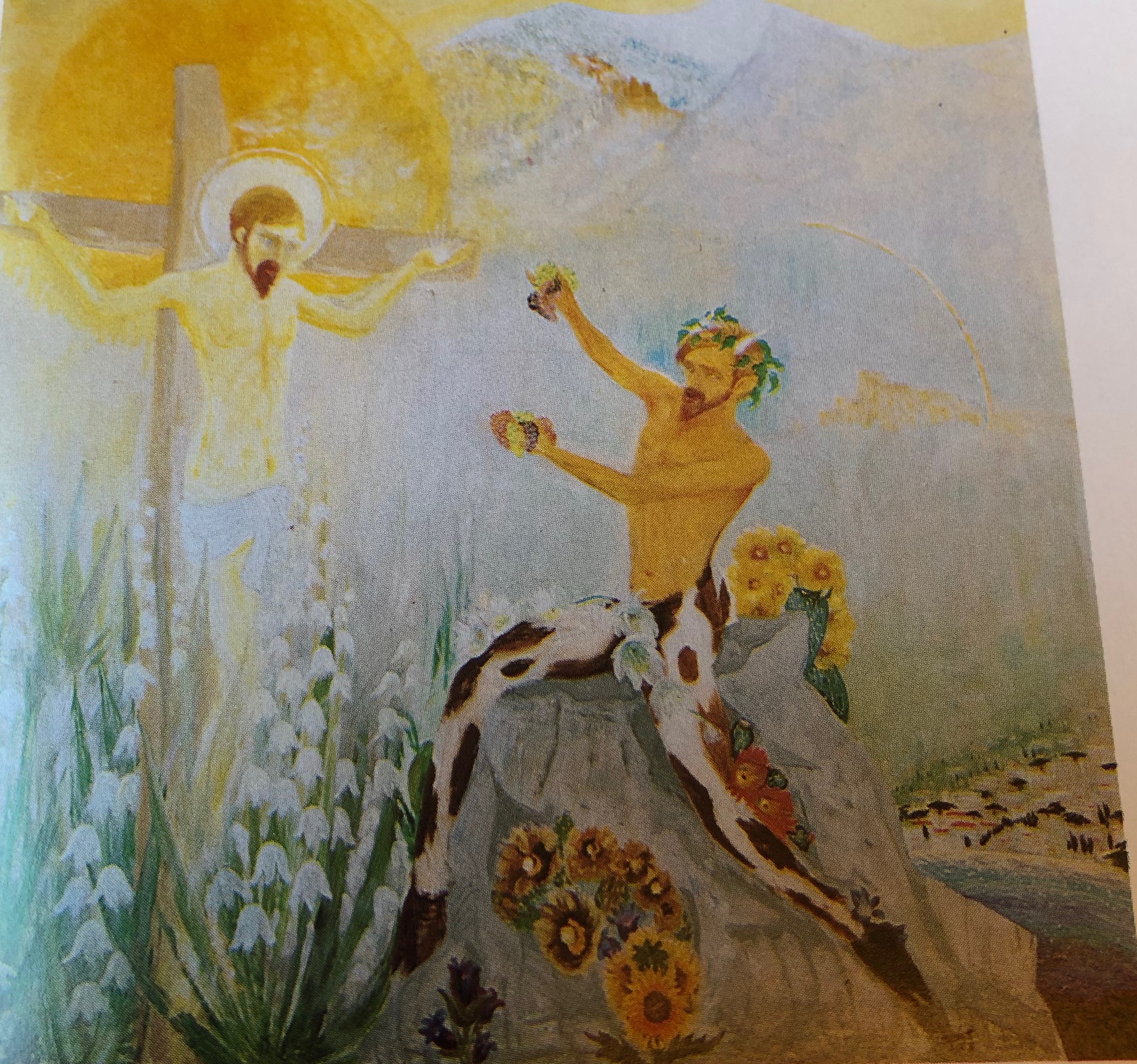

She gave a summary of how Pan is presented in each of the works she had chosen for discussion, which Patricia Merrivale collectively denotes as ‘The Pan Cluster’. ‘Pan in America’ makes a distinction between an original ‘Pan’, which encompasses ‘all’ and is worshipped through contact with the circumambient universe (even today, in part, by those Native Americans who have a sense of the fierce, bristling life force in nature), and the horned caricature of incontinent lust into which he degenerated when Christianity aligned him with the devil. Either way, for Lawrence he is not aligned with a far-reaching humanistic benevolence, as he is for Wordsworth or Emerson. ‘The Overtone’, however, focuses not on the mutual opposition of Christ and Pan, but how they can work in harmony, as the young woman Elsa seeks a man in whom she can honour both; Christ honoured women in his dying, but she needs a Pan for the night time; ‘Pan will give me my children and joy, and Christ will give me my pride’. ‘The Last Laugh’, by contrast, presents Christ and Pan in their enmity – Pan destroys a Church – yet he also elevates a woman in her chastity, and degrades or destroys the men around her, with what Stephen Alexander in his blog post on the story calls ‘sardonic paganism’. In ‘St Mawr’ Pan reverts to alignment with masculinity (this time in the form of a ‘super-sexy stallion’ not a goat, and the American South West not Greece), and in The Plumed Serpent he is associated with an aggressive, destructive masculinity. Cipriano, who has a tuft of goat’s beard, also stabs prisoners. Finally, at the ending of Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928), Mellors recommends Pan as a god for the masses – non-violent, but rendering the masses nymph-like and passively-feminised.

Sue Reid asked Maria to say a little more about the history of Pan. Maria clarified that he was originally an Arcadian wood spirit, older than the Olympian Pantheon, in which he has no place (therefore he is not found in the higher mythology of Hessiod and Homer). Ignored by cultivated Greeks, he was not represented in Greek art until the beginning of the 5thC BC. The tradition of his death at the birth of Christ was started by Plutarch in his Moralia. On this last point, Catherine pointed out that Nietzsche articulates a similar idea to that of ‘Pan in America’ in the epigraph in his 1886 Beyond Good and Evil: ‘Das Christentum gab dem Eros Gift zu trinken – er starb zwar nicht daran, aber entartete, zum Laster’ [‘Christianity gave Eros poison to drink; it did not die, but descended into vice’].

Several of the women present argued that The Plumed Serpent is in fact far more feminist than Maria felt. Sue noted that it turns its heroine Kate ‘into a goddess, which is better than Christianity has managed’. Jane Costin argued that Kate’s role has generally been underrated: she first rejects Western society’s repressive treatment of women, then rejects the other form of female oppression that she finds in the neo-Aztec society. Like Lawrence she has a dual relationship to Pan, of attraction alongside withdrawal, and it is left ambiguous at the end of the novel as to whether Kate will return to Europe or remain. Nahla Torbey agreed that overall it was the woman that was being elevated. Maria remained skeptical.

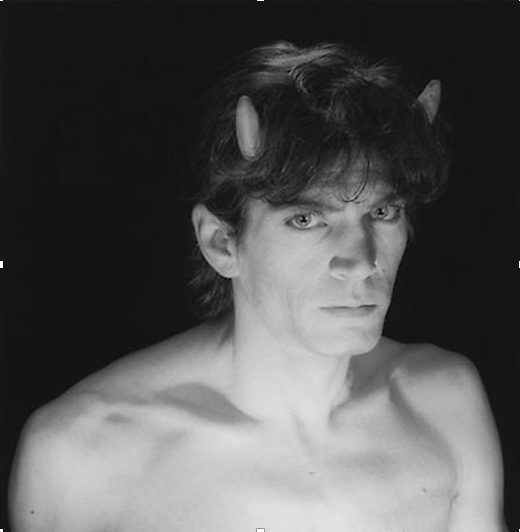

Lara Taylor expressed interest in the fact that Lawrence understands gods as co-existing rather than following one another in succession, as Milton tried to kill off the Classical pantheon in his Paradise Lost. Catherine responded that Lawrence historicises gods – sees Pan as older than Christ and the god of fishes (in his poem ‘Fish’) as older than either, but that they indeed co-exist, though at a given moment in history one of them may be in eclipse for a given portion of humanity. Regarding the co-worshipping of Christ and Pan that is expressed with particular clarity in ‘The Overtone’, she noted that this may shed light on Bulgakov’s 1930s novel The Master and Margarita, which presents both Christ and Woland (who is Satan) as positive characters. She also drew the group’s attention to the double portrait of Lawrence as Christ and Pan made in 1926 and reconstructed (after its destruction by the artist) in 1963:

The artist is in fact Dorothy Brett, model for the character in ‘The Last Laugh’ who is filled by the spirit of Pan (the painting being two years later than the story).

Returning to discussion of that story, we were undecided as to whether the Jewish-looking woman is indeed a prostitute (though Maria considered that her high heels, and invitation of Marchbanks inside for the night, indicated this). Anthony Pacitto suggested that the mention of her Jewish looks was made to align her with the Judeo-Christian tradition which Pan was that night to out destroy (thus the following morning he kills her assumed lover). It was recalled that the Greek god Pan had a tradition of striking people down dead if they saw him in daylight.

Catherine Brown

Maria Thanassa

is an independent scholar and translator. She studied Greek and English Language and Literature at the University of Athens, Greece. She holds an MA in English Literature from Queen Mary College, University of London and a PhD in English Literature from King’s College, University of London. She has taught English and Modern Greek. Her academic interests lie in English and Comparative Literature, Reception Studies, Literary Translation, Greek and European Cinema, and the Arts.

Abstract

In this short paper, I would like to discuss Lawrence’s 1924 essay ‘Pan in America’, before seeing how his unique model of pantheism is played out in his fiction from this period, beginning with ‘The Last Laugh’ and ‘The Overtone’ and ending with selected passages from St. Mawr and The Plumed Serpent.

I shall suggest that the figure of Pan, as imagined by Lawrence, is problematic for feminists and for all women who aren’t interested in playing the subordinate role of nymph – and that what starts as a sardonic form of paganism quickly becomes an apologetic for what some might term phallotoxic masculinity that revels in demonic violence.

Suggested reading:

D. H. Lawrence, ‘Pan in America’, in Mornings in Mexico and Other Essays, ed. Virginia Crosswhite Hyde, (Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 153-164

D. H. Lawrence, ‘The Last Laugh’, in The Woman Who Rode Away and Other Stories, ed. Dieter Mehl and Christa Jansohn, (Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 122-137.

D. H. Lawrence, ‘The Overtone’, in St. Mawr and Other Stories, ed. Brian Finney, (Cambridge University Press, 1983), pp. 3-17

D. H. Lawrence, St. Mawr, in St. Mawr and Other Stories, ed. Brian Finney, (Cambridge University Press, 1983). See the remarks on Pan on pp. 64-67

D. H. Lawrence, The Plumed Serpent, ed. L. D. Clark, (Cambridge University Press, 1987). See pp. 310-12 on Kate’s demon lover, Don Cipriano, with his Pan face and phallic mystery.