Report of the Seventh Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

The Married Man – A Play Reading

Friday 24th April 2020

By Zoom (during period of Coronavirus lockdown; the March meeting was cancelled)

6.30-8.50 pm

ATTENDERS

Catherine Brown, in Kilburn, London

Lara Feigel, in Gloucestershire

Pat Hopewell, in Ladbrook Grove, London

Alex Korda, in Ladbrook Grove, London

James Morgan, in Camarthen

Jane Nichols, in Kent

Iris Orwin, in Bakewell

Hugh Stevens, in Tottenham, London

Brenda Sumner, in Swepstone, Leicestershire

Nahla Torbey, in Wimbledon

Colin Yeates, in Muswell Hill, London

[The Married Man is Lawrence’s fourth play. Written in 1912, it followed A Collier’s Friday Night (1909), The Widowing of Mrs Holroyd (1910), and The Merry-Go-Round (1912) – and preceded The Fight for Barbara (1912), The Daughter-in-Law (1913), Touch and Go (1919) and David (1926), as well as the fragments Altitude (1924) and Noah’s Flood (1925).

It belongs to that short and excited period in Lawrence’s life between his meeting of Frieda Weekley in March 1912, and his elopement with her at the beginning of May 1912. Like The Fight for Barbara it contains a character who resembles her (Elsa Smith), but unlike Barbara she appears late in the play and has a relatively minor role, as fits the fact that Frieda was not yet central in Lawrence’s life.

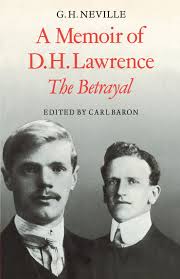

Rather, the play is more occupied by one of Lawrence’s close male friends of his adolescence and College years, George Henry Neville. Like Lawrence, Neville was of a mining family and won a scholarship to Nottingham High School. He and Lawrence holidayed together in Blackpool in 1910, and (together with Ada Lawrence and Louie Burrows) in Prestatyn, North Wales, in 1911. Soon after meeting Frieda Lawrence found out that Neville, ‘my very old friend, the Don Juanish fellow’, had clandestinely married and now had a son (1L 373); six years earlier he had made a different girl pregnant. His wife and child were living in Stourbridge, West Midlands, whilst he worked as a Head Teacher in Bradnop, Staffordshire. In Eastwood Lawrence – who was still recovering from the bout of pneumonia that had made him leave his Croydon teaching position – missed the company of his friend and decided to visit him. His visit to Staffordshire lasted from 25th – 31st March 1912. Lawrence describes the visit in the following, somewhat rakeish, terms: ‘Diddler and I dodge about at evening’; ‘In the evening Diddler took me a tat-tah, and of course got lost’; [to May Holbrook he writes he will come over] ‘on Sunday. I suppose J[essie] will be at the cottage … I said nothing to Mrs Weekley about coming over’ (1L 377 ff).

On returning to Eastwood he combined elements of his own and Neville’s situations in The Married Man, with himself (roughly) in the character of William (Billy) Brentnall, and Neville in Dr George Grainger. He had finished it by 23rdApril and called it ‘a comedy – middling good’ (1L 386). He had received a particular impetus to write a play just before his visit to Neville, as some of his play scripts that gone missing had reappeared and been sent to him by Edward Garnett. In addition, on 9th April he had been given, and read, Chekhov’s The Seagull and The Cherry Orchard. However, after finishing this play neither this nor his previous plays were performed, and at that stage he was in any case rapidly more interested in eloping with Frieda Weekley than in promoting or working on his plays (Plays 1 xxxi-xxxii).

The play received nine performances by RADA students in London in October 1997, and a Zoom reading by the members of this group on 24th April 2020. I am not aware of any other performance.]

THE READING

Lawrence would doubtless have hated Zoom for the same reasons that he disliked cinema: fake contact, no touch. But we were at least ‘live’, and the session was not recorded. Serendipity is harder to achieve online, and, unlike with The Widowing of Mrs Holroyd at our reading in December 2019, we did not pull names of parts out of a hat, but rather cast ourselves as volunteers: Colin Yeates as Grainger, James Morgan as Brentnall, Jane Nichols as Mrs Plum, Hugh Stevens as Jack Magneer, Nahla Torbey as Sally Magneer, Alex Korda as Mr Magneer, Lara Feigel as Annie Calladine, Jane Nichols as Emily Calladine, Pat Hopewell as Ada Calladine, Catherine Brown as Elsa Smith, Jane Nichols as Gladys, Alex Korda as Tom, and Lara Feigel as Ethel Grainger.

The play, it turns out, is difficult to keep track of when not visualised. It consists largely of rapidly-shifting constellations of heterosexual couples, until the neglected wife Ethel’s appearance at the end simplifies the play to a tense and unresolved negotiation between her and husband, with Brentnall and his friend Elsa offering a chorus of respectively Lawrence- and Frieda-like voices.

The play has some similarities to The Daughter-in-Law which followed it the following year – Ethel has £70 of her own money to Minnie’s £100; the recently-married couple spends much of the play apart; at the end they are together, though more tensely so in The Married Man. Over the course of the shifting constellations – often manifested as couples ‘spooning’ behind newspapers, though Mr Noon’s keyword is not actually used in the play – Grainger is variously connected to Annie, Ada, Sally and Ethel, and Brentnall is connected to Sally, Ada and Elsa. The fugue-like variations are even more complex and rapid than are those of The Merry-Go-Round, and they anticipate those of John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, which it turns out is not only in debt to The Fight for Barbara amongst Lawrence’s plays (though the debt to the later play is particularly obvious). The sexual freedom also anticipates the Bohemianism depicted in Aaron’s Rod (1922). Although the women are in the majority, as they are in most of Lawrence’s non-Biblical plays (and as is reflected in their titles), this does not work to their advantage. Even before the War decimated the young male population, Iris Orwin posited, decent husbands were in short supply.

We agreed that the play demonstrates Lawrence’s considerable gift for stage writing, notably in the rapid-fire dialogues. Hugh Stevens proposed that Lawrence wrote the play at great speed, and had not necessarily thought through precisely how the complex scenes involving the couples behind newspapers would be blocked. Nor had he necessarily anticipated whether the play would pass the Lord Chamberlain’s censorship; it is certainly the most risqué of his plays. That aspect does not, however, pertain to the scenes in which Grainger and Brentnall are seen sharing a room and dressing, even sharing a bed; Iris Orwin and James Morgan reminded us of the Morecombe and Wise sketches (of the 1940s-80s) in which the comedy duo appear in bed together without any connotation of sexuality. We have collectively forgotten the non-sexual bed-sharing that used to be commonplace. That said, Brentnall is aware of Grainger’s attractiveness; he says: ‘There’s something fascinating about George. He can’t help it. The women melt like wax before him. They’re all over him. It’s not his beauty, it’s his manliness. He can’t help it’(1 Plays 224). John Worthen, in his biography of Lawrence’s earliest years, describes the attractiveness that his ‘athletic and not particularly intellectual’ friends Alan Chambers and George Neville had for Lawrence (D. H. Lawrence: The Early Years, 50, 156).

With regard to Elsa’s breezy disregard of technical sexual fidelity, Colin Yeates helpfully posited that distinction between loyalty and fidelity on which so many Bloomsbury marriages, as well as later twentieth-century ‘open’ marriages (now apparently less in fashion), seem to have been predicated. Those marriages were distinctly bourgeois, but have their parallel in the countless working-class and peasant marriages across time and space which have been durable whilst accommodating the exchange of sexual partners.

The question of class in this play, however, is a complex one. In general the class trajectory of characters in Lawrence’s first plays seems to move upwards from A Collier’s Friday Night to The Widowing of Mrs Holroyd (with its engineer) to The Merry-Go-Round (with its German vicar) to The Married Man (where Elsa appears as ‘A lady in a motor cloak and wrap’ [1 Plays 216]) to The Fight for Barbara (where most of the characters are bourgeois or higher). However, many of the characters in The Married Man seem of indeterminate class; as we discussed, being a doctor in 1912 was not such a definite middle-class marker as it is today, and Grainger pronounces himself willing to move anywhere for a job. In some respects, as James Morgan said, the main characters seem lower-middle class; yet Brentnall has rooms in London. This indeterminacy belongs perhaps less to vagueness on Lawrence’s part than to the greater class-fluidity of his period – facilitated in large part by the recent extension of free education to working class men and women. This is commented upon explicitly in Women in Love (where two daughters of a carpenter become friends with an aristocrat), and it was of course experienced in Lawrence’s own life, through the education that gained him entry to Nottingham University, to a teaching job in Croydon, and thence to London’s literary world.

Lawrence’s play may not have reached many people, but it cheered us, and brought us together, during a pandemic that is unprecedented in England since that of a century before – which Lawrence lived through, and will, together with our current pandemic, be discussed at our meeting in May.

Dr. Catherine Brown