Report of the Twenty-Seventh Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Jim Phelps

‘Whether or Not?’

Thursday, 23rd March 2023

By Zoom

18.30-20.00 UK time

ATTENDERS

24 people attended, including, from outside of England, Jim Phelps, Geoff Haresnape and Val in Cape Town, Shirley Bricout in Brittany, John Worthen in Germany, Kathleen Vella in Malta, Muzumal at Gomal University in Pakistan, Shanee Stepakoff in Essex Connecticut, Phil in West Virginia, Keith Cushman in North Carolina, Tina Ferris in South Carolina, and Aaron in the Bronx.

INTRODUCTION

Jim focused on the two versions of Lawrence’s Nottinghamshire dialect ballad ‘Whether or Not’, from autumn 1911 and November 1927 respectively, arguing that their plot dynamics and outcomes act as pointers to outcomes in Lawrence’s narratives more generally. In the 10-section first version, Lizzie Stainwright is engaged to a 25-year-old policeman Timothy Merfin who lodges with a 45-year-old widow Mrs Naylor. Timmy gets Mrs Naylor pregnant, claiming to Lizzie (when challenged) that he acted out of frustration after unconsummated but sensual contact with her. Lizzie confronts Mrs Naylor, and they argue, inconclusively. Finally, Lizzie resolves to marry Timmy, suggesting that he give Mrs Naylor his money, and that they themselves bring up the latter’s child. The 11-section second version largely resembles the former except that at the end Timmy rejects Lizzie, accusing her of having shown him less generosity than the widow has shown, and of being ‘too much i’ th’ right for me’, but also declaring that he will not marry the widow; rather he will go away.

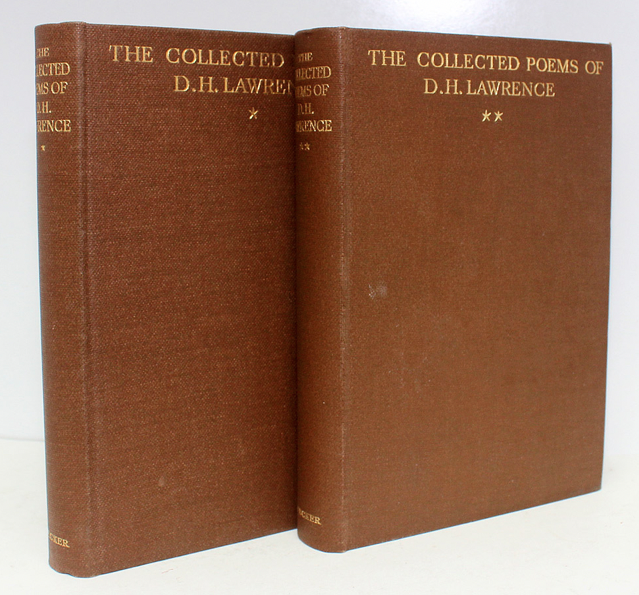

When editing his Collected Poems in 1928, Lawrence at the age of 42 reflected on poems that he had written over two decades before. In his ‘Foreword’ he says that in some of those poems his true ‘demon’ had been obfuscated by his merely ‘ordinary self’, which required of him a process of revision: ‘It has taken me twenty years to say what I started to say, incoherently, when I was nineteen’; ‘some of the later ones had to be altered, where sometimes the hand of commonplace youth had been laid on the mouth of the demon. It is not for technique these poems are altered: it is to say the real say’. In particular he recalls that Edward Garnett ‘disliked the old ending to “Whether or Not”. Now I see he was right, it was the voice of the commonplace me, not the demon. So I have altered it’ (Poems1 653).

READING

‘Whether or Not [1]’ (Poems3 1642-1649)

‘Whether or Not’ (Poems1 43-51)

‘Morality and the Novel’ (STH 171-6)

‘Foreword to Collected Poems’ (Poems1 651-4)

‘Note to Collected Poems’ (Poems1 655-6)

(the references are to the Cambridge Edition of Lawrence’s works, the Poems appearing in three volumes, with variants and unpublished versions in the third volume).

THE PRESENTATION

Jim started by noting that in his ‘Foreword’ to his Collected Poems Lawrence seems to be inviting us to do precisely what we were gathered to do – to compare the earlier and later versions his poems. On balance Jim agreed with Lawrence’s assertion that the earlier version of ‘Whether or Not’ was expressive of the ‘commonplace’ Lawrence, ready to make compromises in the service of social conformity, whereas in the later version his ‘demon’ was allowed to express itself fully in Timmy’s final decision. That is, the first version ends as well as possible for all three characters, except that it subordinates the couple to convention, and would not have given the child a healthy context in which to grow up. The second ending is in a profound sense more realistic, and realises some of the hints existing in the first version (for example Timmy’s reproaches of Lizzie). There are in the later version the glimmerings in Timmy of a proper reverence for sex (in his revulsion from the kind of sex that he had with the widow). Jim related this shift of versions to that enacted in Lawrence’s poem ‘Snake’, in which the voice of the speaker’s ‘accursed human education’ initially overrides his demon’s instinctive admiration for the snake. Of Lawrence’s three dialect poems, ‘Whether or Not’, the only one that Lawrence that revised, and it was clearly important to him to do so.

Jim noted that Lawrence wrote the first version of the poem when he was living in Croydon and working through the complexities of his relationships to Jessie Chambers, Louie Burrows and other women. There was always the threat of creating a pregnancy out of wedlock, as his friend George Neville had done; as Lawrence told Jessie, ‘Thank God I’ve been saved from that so far’. By the time that he created the revised version of the poem he had long known Frieda, was writing the final version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, with its own commitment to its protagonists’ ‘demons’, and rejection of unfulfilling marriage.

Jim related the plot to those of Lawrence’s play The Daughter-in-Law (completed in January 1913) and story story ‘The Last Straw’/‘Fannie and Annie’ (completed May 1919), both of which also concern an interloper pregnancy, and both of which, like the first version of ‘Whether or Not’, end with the wives confessing their love for their flawed husbands. In ‘Whether or Not’ there is a hint from Lizzie that, as in The Daughter-in-Law, the male protagonist has been unhealthily dominated by his mother. Jim speculated that Lawrence might have similarly revised these works, had there been an equivalent opportunity to do so; indeed, when first submitting ‘The Last Straw’ for publication, he indicated that he would be willing to change the ending. Finally Jim adduced the ‘Pansy’ ‘Good Husbands Make Unhappy Wives’, with its sentiment that good husbands make wives still unhappier than bad husbands, as of possible relevance to the queasy truce achieved by the end of the first version of ‘Whether or Not’.

However, he acknowledged that certain critics, including Keith Sagar, David Ellis and Keith Cushman, thought the opposite of himself – that it was the second version of the poem that was incongruous.

THE DISCUSSION

John Worthen promptly joined this group. He said that the second version of ‘Whether or Not’ was a good example of Lawrence’s late works in which he understandably (given his sense that he was running out of biological time) took short cuts, became didactic, drove arguments hard, and wrote as ‘the artist’ rather than as his demon – and an artist not performing particularly well at that. He pointed to what he saw as the inferiority of both the verse and dialect in section xi of the final version in comparison to the entirety of the first version, highlighting the phrases ‘bit o’ cunt’ and ‘a permanent fit’ as particularly contrived. Phil agreed with John in finding the first version a depiction of social reality, and the second version as a didactic vehicle of Lawrence’s desiderata. Terry Gifford agreed with Jim that the first version had a socially-satisfactory ending, but argued that it was one that presented Lizzie as generous in her response to the complexity of the situation and in her decision to commit to Timmy (though John doubted that she still loved him: ‘I were fond o’ thee’). Vic agreed with John and Phil that in the second version Lawrence put his thumb in the balance.

Jim responded that he himself had mixed feelings about the second version, but that ultimately he understood it as a sympathetic representation of Timmy’s hurt pride as a mother-dominated son exploited or bossed by his respective lovers. Steve thought that the second version revealed the sexual maturity of an author who had learned that marriage required more than just sexual attraction, and to whom use of the word ‘cunt’ came naturally, as it does in Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Catherine thought that in both versions of the poem the widow is an extraordinary creation – independent, confident, sexed, frank, uncalculating, un-selfpitying – but that the rhetoric of the second ending approves Timmy’s social and financial abandonment of her. Vic agreed, and said that he thought both women were represented as considerable. With regard to the age gap in Timmy’s relationship with his landlady, Shirley was reminded of ‘The Blue Moccasins’, in which a 45-year-old woman marries a man 20 years her junior. Steve and Geoff questioned whether the widow was as physically repulsive as Lizzie and her mother represent her as being (in a dramatic poem no objectivity on this point can be found), and Jim agreed that there must be something powerfully attractive about her, noting her name Naylor. Catherine added that Timmy gives no hint of not wanting to marry the widow because it would be demeaning for him to marry someone so repulsive; Nahla thought that his reasons for rejecting her, far from being related to age, appearance or class, were purely demon-related. Jim returned to the poem ‘Good Husbands make Unhappy Wives’, suggesting that in the second version Timmy avoided becoming either a good, or a bad, husband in the poem’s senses of those adjectives. Lawrence himself, by contrast, aspired to be a ‘good’ husband in a third, Lawrencian, way.

Jim asked how well either version of the poem mapped onto the present day, with its birth control and abortion rights. Catherine was struck by the contrast between the position of the widow (and of Bertha in The Daughter-in-Law) with that of middle-class women under similar circumstances –especially shortly before, in the Victorian period. In Nikos Kazantsakis’s 1946 novel Zorba the Greek a Cretan widow has a one-night-stand with an Englishman, and as a result is stoned to death by her fellow villagers outside the village church. Mrs Naylor, it seems, will suffer negligible social stigma for her fornication and illegitimate child. Jim noted that toleration of such phenomena, which is today’s norm, was at the time class-related, and reflected in the high proportion of working-class children who were born illegitimately. Catherine notes too that amongst the middle-classes in 1911 there would have been social, if not also legal, penalties for the breaking-off of an engagement, whereas Timmy evidently fears no such punishment. Finally Catherine observed that Timmy today would certainly not be sacked from the police force for his actions – perhaps most especially not from the Metropolitan Police Force, with its currently-scandalising culture of misogyny. Anne Gallacher responded that Lizzie’s disrobing of Timmy from his uniform reveals his sexual urges to be a universal human experience, which can only to a limited degree be controlled by authority.