Report of the Thirtieth Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Catherine Brown

A Walking Tour of Lawrence’s Hampstead

Friday 30th June 2023

In person

13.00-15.00 UK time

ATTENDERS

Eleven people attended including Catherine Brown, Anne Gallagher, Vic and Ilse West, Nahla Torbay and her son, Blake Matich, James Walker and his friend, Stephen Alexander and Steve Rawsten.

Outside 1 Byron Villas, Vale of Health

INTRODUCTION

The walking tour, for which the guiding notes appear below, was written by John Worthen and adapted and enlarged by Catherine Brown. It was first delivered by John and Catherine during the 14th International DH Lawrence Conference, London Calling: Lawrence & the Metropolis, which took place 3rd-8th July 2017 in London. 30th June 2023 was its second iteration as a guided tour; anyone is welcome to use the notes below to guide themselves round [directions are given in square brackets].

The tour started at Hampstead Tube Station and finished at Hampstead Heath Overground Station. It covered 2.1 miles and took two hours.

It included:

- Hampstead Tube Station, which Lawrence knew and used

- The home of Dollie Radford on Well Walk, where Lawrence and Frieda lived in 1917

- The home of the Weekley parents on Well Walk, where Frieda left her two daughters when joining Lawrence to travel to Germany in 1912

- 1 Byron Villas, Vale of Health, where Lawrence and Frieda lived in the second half of 1915

- Whitestone Pond, near where Lawrence saw the Zeppelins over London in September 1915

- Catherine and Donald Carswell’s house, where Lawrence and Frieda lived in 1923

- Various places associated with the short story ‘The Last Laugh’, including St Stephen’s Church

- The house of Ivy and Barbara Low on Holly Bush Mount

- The houses of Dorothy Brett and John Middleton Murry on Pond Street during 1923-24

NB

The Cambridge Edition of the Letters and Works of D.H. Lawrence (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 1979-) has been cited below, particularly including: The Cambridge Edition of the Letters of D.H. Lawrence, 8 vols, ed. James T. Boulton et al (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979-2000), and The Woman Who Rode Away and Other Stories, ed. Dieter Mehl and Christa Jansohn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995); this contains the short story set in Hampstead, ‘The Last Laugh’.

There is also a reference to Edward Nehls, D.H. Lawrence: A Composite Biography, 3 vols (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1957)

INTRODUCTION TO THE TOUR

Welcome to the Montmartre of London. The analogy isn’t exact, but it is on a hill – and Bohemians, artists and psychoanalysts have been associated with it.

Since we will not be visiting the locations in order of chronological relevance, it may help to sketch out the chronology of Lawrence’s association with Hampstead first.

Lawrence first visited West Hampstead in 1908; his aunt Ada’s relations, the Hungers, lived at Hill Crest, Ardwick Road, and Lawrence stayed with them more than once. Louie Burrows, too, stayed with the Hungers in 1911.

Lawrence was taken to central Hampstead by Ford Madox Hueffer, and it was here that he was introduced to many of the figures of literary London: Ernest Rhys (48 West Heath Drive), H. G. Wells (17 Church Row) on 9 November 1909, and Rachel Annand Taylor on Saturday 15 October 1910, while staying with the Hungers. He saw Edward Garnett, perhaps in 1912 in Pond Street, and certainly in 1913 at Downshire Hill.

From 1900 to 1912, Frieda was regularly in Hampstead, staying with her children at her parents in law’s house at 40 Well Walk. She may well have got to know Ernest and Dollie Radford via the Weekleys, since they were nearby at no 32; Dollie, a poet and playwright, was to become a loyal friend of the Lawrences.

Hampstead was where Lawrence and Frieda met psychoanalysts: Barbara Low (via her niece Ivy) in the early summer of 1914, in Holly Bush Hill; via her, the Eders (at 103 Hampstead Way, in West Hampstead), and via them, Ernest Jones. Through Barbara Low he also met Catherine Jackson (later Carswell) at Holly Bush House.

In the summer of 1915, Lawrence and Frieda took their first London lodgings at 1 Byron Villas in the Vale of Health; Frieda first moved in alone, then Lawrence joined her, and they stayed there until the end of the year. It was on their way home to this house that they saw the Zeppelin raid on London on 8thSeptember 1915.

When they returned to London in 1917, having been exiled from Cornwall, they spent 15th-21stOctober staying with Dollie Radford at 32 Well Walk, four doors from where Frieda used to live with her in-laws. (In March 1917, Frieda had seen her children at Mark Gertler’s studio in Hampstead: he lived in Rudall Crescent, but his Studio was in Well Road).

In 1923, Frieda lived in a flat in the Carswells’ house at 110 Heath Street, and was joined there by Lawrence. Hampstead is where Lawrence wrote his 1923 essays on England, saw Murry and Dorothy Brett, and went to the Café Royal for his ‘last supper’ with friends before returning to New Mexico. Lawrence and Frieda left Hampstead on 23rdJanuary 1924.

On 28th September 1926, it was from 30 Willoughby Road, Hampstead (where Lawrence and Frieda had lived since 16th September in lodgings found for them by Mark Gertler) that Lawrence spent his last night in England, before leaving the country for ever.

1] HAMPSTEAD TUBE STATION

From here, a five minute walk down Heath Street and right onto Church Row would take us to H.G. Wells’s house at 17 Church Row.

Instead, we will go down the High Street and take a left onto Flask Walk, where on our left we pass ‘Baths and Wash Houses 1888’, which provided drinking and bathing facilities for the poor of the neighbourhood who did not have running water at home.

On our right we pass the Marie Stopes house. Stopes (1880-1958) was a campaigner for eugenics, birth control and women’s right; she opened birth control clinics, and in 1918 published Married Love.

Once we reach the Wells Tavern pub, stop and look one street parallel to the North. There is 1 Wells Road, where Mark Gertler had his studio, and where Frieda saw her children by official arrangement in March 1917.

2] 32 WELL WALK

[This is immediately next to the Wells Tavern on Well Walk]

This was the home of Dollie Radford, friend of the Lawrences and near neighbour of Ernest Weekley’s parents. Lawrence and Frieda saw Dollie there in the autumn of 1915. The fact that she had a telephone proved useful for urgent communications between Lawrence and his agent JB Pinker during the crisis of the seizing and banning of The Rainbow in October 1915.

In October 1917 Lawrence and Frieda returned to this house in distress, having been expelled from Cornwall on suspicion of spying for Germany. Dollie, ever faithful, took them in – but her own health was not good, and she was nursing her husband. She was nervous at hosting guests who had to report regularly at the local police station – although, when the Lawrences did so, the police showed little interest. From here they moved to stay with the poet H.D. on Mecklenburg Square.

In Kangaroo, this period of refuge in Hampstead is fictionalised as follows:

‘They came to London, and he tried taxi after taxi before he could get one to take them up to Hampstead. He had written to a staunch friend, and asked her to wire if she would receive them for a day or two. She wired that she would. So they went to her house. She was a little delicate lady who reminded Somers of his mother, though she was younger than his mother would have been. She and her husband had been friends of William Morris in those busy days of incipient Fabianism. Now her husband was sick, and she lived with him and a nurse and her grown-up daughter in a little old house in Hampstead.

Mrs Redburn was frightened, receiving the tainted Somers. But she had pluck. Everybody in London was frightened at this time, everybody who was not a rabid and disgusting so-called patriot. It was a reign of terror. Mrs Redburn was a staunch little soul, but she was bewildered: and she was frightened. They did such horrible things to you, the authorities. Poor tiny Hattie, with her cameo face, like a wise child, and her grey, bobbed hair. Such a frail little thing to have gone sailing these seas of ideas, and to suffer the awful breakdown of her husband. A tiny little woman with grey, bobbed hair, and wild, unyielding eyes. She had three great children. It all seemed a joke and a tragedy mixed, to her. And now the war. She was just bewildered, and would not live long. Poor frail tiny Hattie, receiving the Somers into her still, tiny old house. Both Richard and Harriett loved her. He had pledged himself, in some queer way, to keep a place in his heart for her forever, even when she was dead. Which he did’. (Kangaroo 247:20—248:11).

Dollie Radford died in 1920, three years after this incident.

3] 40 WELL WALK

The painter John Constable (1776-1837) rented a house in Hampstead almost every summer between 1819 and 1826, and eventually moved to Hampstead, and this house (40 Well Walk) in 1827. He found that he could unite ‘a town and country life’ by having his studio in London and living in Hampstead.

This later became the house of Ernest Weekley’s parents, and their daughter-in-law Frieda stayed with them here on a number of occasions. For example, in December 1899: ‘I’m here in Hampstead for two days, without Ernest, the air is so good for me and I’m very often very much alone in Nottingham: three evenings a week Ernest is giving lectures to workers.’ Or August 1900, when Frieda stayed here whilst Ernest taught in Cambridge: ‘I like it very much here, Ernst’s family is so natural and sensible and simple! I charge all around Hampstead Heath, it is so lovely!’

It was at this house that Frieda left her two daughters before going to meet her husband’s former student, DH Lawrence, at Charing Cross, to catch the boat-train to Germany with him on 3rd May 1912. After this elopement, Ernest’s parents and sisters took over their upbringing.

Walking further towards the Heath, see on the left hand side the home of JB Priestley from 1928-32.

4] HAMPSTEAD AND ITS HEATH

[On the far side of East Heath Road, find the diagonal path running North-West cutting across a corner of Hampstead Heath straight to the Vale of Health Pond]

The Heath was mainly common land since the first millennium; in the Middle Ages parts of it became private estates, but over the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries much of it was returned to the public.

In the nineteenth century Hampstead became a centre of British Judaism; today around 10% of the inhabitants are Jewish, compared to 0.5% of the UK population as a whole. In Lawrence’s time as subsequently, this community has had a strong association with psychoanalysis; when Freud fled Nazi Austria into exile in 1938, it was to Hampstead that he came. The area’s erstwhile association with ‘champagne socialism’ has recently been somewhat weakened by an increase in its share of Conservative voters; Hampstead currently has more millionnaires per square metre than any other part of the UK.

When the Lawrences moved to the Vale of Health in 1915 they had very little money; people similarly-circumstanced today are less likely to be able to afford to rent there. The name ‘Vale of Health’ was first recorded in 1801, and the area soon became middle class and acquired literary associations. In 1815 James Leigh Hunt moved there; Byron, Shelley, Coleridge and Crabbe visited him there, beginning the association of Hampstead with liberalism. By 1890 there were 53 houses in the Vale, and by 1911 it was criticised as vulgarized by its tavern, tea gardens and fun fair. Literary people continued to move there, however; Rabindranath Tagore lived at no. 3 Villas on the Heath in 1912, John Middleton Murry lived at no. 1A The Gables in 1926, Sir Compton Mackenzie lived at Woodbine Cottage from 1937 to 1943, Henry Lamb painted his portrait of Lytton Strachey there in 1912, and Stanley Spencer lived there from 1914 to 1927.

[On reaching the Vale of Health Pond follow the path to the right (East) of it; once you have passed it take the first street on the left (passing a caravan park on your right) onto the Vale of Health. A little further up is the section of the street called Byron Villas; look for number 1 on your left.]

5] 1 BYRON VILLAS, VALE OF HEALTH

Lawrence and Frieda inhabited the lower half of this small terraced house from August to December 1915. In mid-May 1915, Frieda had originally found rooms at 2 Park Hill Road, off Haverstock Hill in South Hampstead, but they failed to apply in time and she had to hunt again; at the start of June she discovered Byron Villas in the Vale of Health. Her ‘little flat’ (as originally conceived) was to give her a place of her own in the summer of 1915, as a base for her attempt to see her children. Lawrence, who did not care for London, was not keen to join her there; but it was nonetheless exciting for them both to finally have a place of their own, and furniture of their own. Friends gave them housewarming presents, and the Lawrences’ trip to Caledonian Market to buy a chair became the basis for the ‘A Chair’ chapter of Women in Love (written soon thereafter in Cornwall).

The Byron Villas flat cost £36 a year, but it was only available from 31st July. As a result, the Lawrences remained based in Greatham until the end of July, and moved into Byron Villas on 4th or 5th of August. From here, on 11th August 1915, Frieda went to see her children officially for the first time since she had parted from them (also in Hampstead) on 3rd May 1912. This was the house to which they were returning when they saw the Zeppelin raid over London on 8th September 1915. Here they hosted E. M. Forster, Lawrence’s Eastwood friend and mentor William Hopkin, and Bertrand Russell. Here Lawrence planned The Signature with John Middleton Murry, revised the essays for Twilight in Italy, and heard the news of The Rainbow’s suppression in November. On this, he decided to leave for the USA, but this was prevented by the authorities, so on 21st December 1915 the Lawrences gave up the flat, and went first to the Midlands, and then, on 30th December, to Cornwall. Catherine Carswell and Mark Gertler acquired the furnishings from Byron Villas, which Lawrence eventually re-acquired for their cottage in Higher Tregerthon near Zennor (near St Ives).

[On reaching the end of Byron Villas turn right; on your left you pass a former residence of Lord Northcliff, a newspaper tycoon and founder of titles including The Daily Mail; his family still owns the paper. He owned a greater proportion of the British media than does Rupert Murdoch today (2023), and owned left wing as well as right wing papers. On reaching the end of the road having passed Lord Northcliff’s house on your left, strike out across another section of Hampstead Heath. Steer a middle course along small tracks, and you should find yourself climbing steeply towards Spaniards Road, where you should emerge with Jack Straw’s Castle on the opposite side of the road.]

6] JACK STRAW’S CASTLE

There was road access from Byron Villas to Spaniard’s Road (the main road up the North-West side of the Heath) but Lawrence preferred to direct his visitors to walk from Hampstead Station up Heath Street and then across a section of the Heath, taking the footpath opposite Jack Straw’s Castle (then an inn, now a gym). Note the First World War memorial on the right hand side.

[From here walk left (South) down to:]

7] WHITESTONE POND

This was mentioned by Lawrence in letters as one of the things for his guests to look out for when coming up from Hampstead Station, before going across the Heath to the Vale of Health.

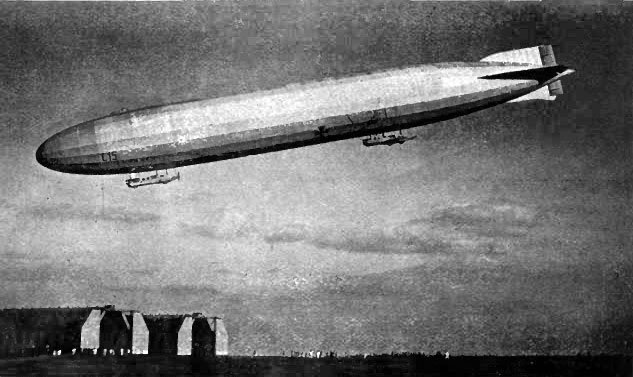

It must have been very near here that the Lawrences saw Zeppelin L-13, piloted by Kapitanleutnant Heinrich Mathyon, on 8th September 1915.

Its length was remarkable:

This is how Lawrence describes the incident, which occurred when he and Frieda were returning home to Byron Villas from dining with friends:

‘Last night when we were coming home the guns broke out, and there was a noise of bombs. Then we saw the Zeppelin above us, just ahead, amid a gleaming of clouds; high up, like a bright golden finger, quite small, among a fragile incandescence of clouds. And underneath it were splashes of fire as the shells fired from earth burst. Then there were flashes near the ground – and the shaking noise. It was like Milton – then there was a war in heaven. But it was not angels. It was that small golden Zeppelin, like a long oval world, high up. It seemed as if the cosmic order were gone, as if there had come a new order, a new heavens above us: and as if the world in anger were trying to revoke it. Then the small long-ovate luminary, the new world in the heavens, disappeared again.

I cannot get over it, that the moon is not Queen of the sky by night, and the stars the lesser lights. It seems the Zeppelin is in the zenith of the night, golden like a moon, having taken control of the sky; and the bursting shells are the lesser lights.

So it seems our cosmos is burst, burst at last, the stars and moon blown away, the envelope of the sky burst out, and a new cosmos appeared, with a long-ovate, gleaming central luminary, calm and drifting in a glow of light, like a new moon, with its light bursting in flashes on the earth, to burst away the earth also. So it is the end – our world is gone, and we are like dust in the air.

But there must be a new heaven and a new earth, a clearer, eternal moon above, and a clean world below. So it will be.’ (2L389-90).

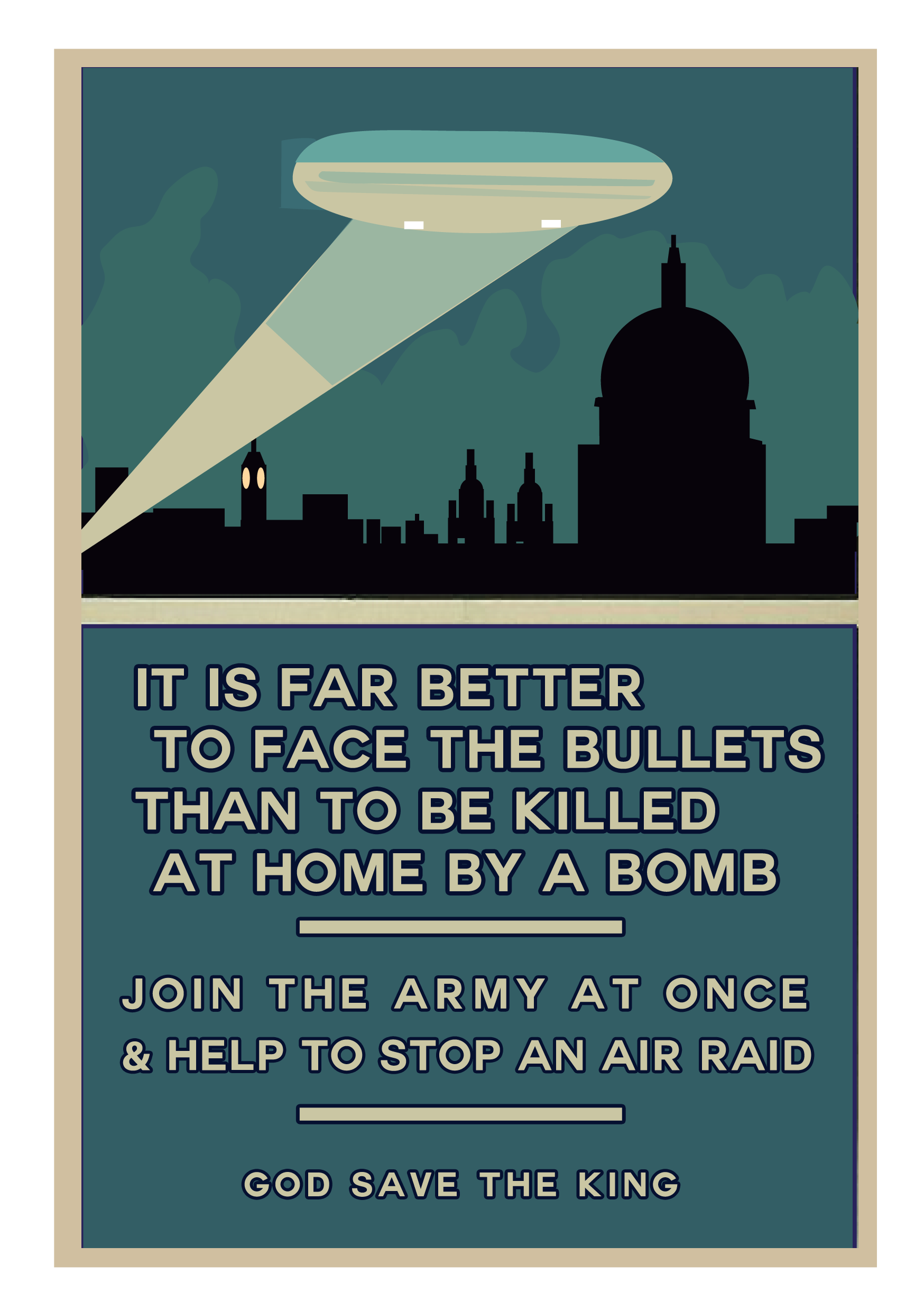

The Zeppelin raid was used in a new, British recruiting campaign in the autumn of 1915 (conscription was only introduced in January 1916):

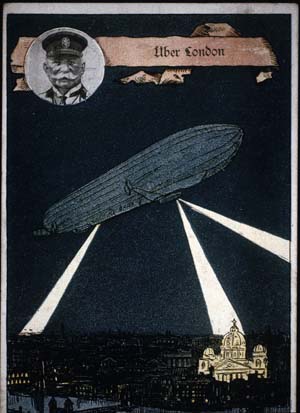

But the defining image of the enormous Zeppelin was also used in Germany, very differently: the Zeppelin in ‘Over London’ is not caught in the lights of searchlights on the ground, but itself lights up the buildings which are its targets (notably St Paul’s Cathedral):

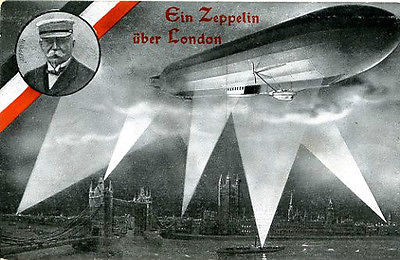

And its machine guns will of course send John Bull flying: ‘With our obedient Zeppelin – we intend to make life hot for ’em’. A little more realistic was a postcard in which, nevertheless, the Houses of Parliament appear next to Tower Bridge:

L-13 was probably at around 10,000 feet (Zeppelin pilots had learned to fly above the range of anti-aircraft fire, which had originally been deadly for them). L-13 had crossed the North Sea and made its way south via Cambridge towards London. The bomb-load included a 300 kilograms (660 lb) bomb, the largest yet carried. This exploded near Smithfield Market, destroying several houses and killing two people. More bombs fell on the textile warehouses north of St Paul’s Cathedral, causing a fire which despite the attendance of twenty-two fire engines caused over half a million pounds of damage. The Zeppelin then turned east, dropping its remaining bombs on Liverpool Street station. The Zeppelin was the target of concentrated anti-aircraft fire, but no hits were scored and the falling shrapnel caused damage and alarm on the ground. The raid killed in total twenty-two people and injured eighty-seven that night. The event was also described in Kangaroo:

‘At night all the great beams of the searchlights, in great straight bars, feeling across the London sky, feeling the clouds, feeling the body of the dark overhead. And then Zeppelin raids: the awful noise and the excitement. Somers was never afraid then. One evening he and Harriet walked from Platts Lane to the Spaniards Road, across the Heath: and there, in the sky, like some god vision, a Zeppelin, and the searchlights catching it, so that it gleamed like a manifestation in the heavens, then losing it, so that only the strange drumming came down out of the sky where the searchlights tangled their feelers. There it was again, high, high, high, tiny, pale, as one might imagine the Holy Ghost, far, far above. And the crashes of guns, and the awful hoarseness of shells bursting in the city. Then gradually, quiet. And from Parliament Hill, a great red glare below, near St. Paul’s. Something ablaze in the city. Harriet was horribly afraid. Yet as she looked up at the far-off Zeppelin she said to Somers:

“Think, some of the boys I played with when I was a child are probably in it.”

And he looked up at the far, luminous thing, like a moon. Were there men in it? Just men, with two vulnerable legs and warm mouths. The imagination could not go so far.’

(K215:36—216:18)

HG Wells’s prophetic 1907 novel The War in the Air envisaged a future war with Germany that would be fought in the air. At the end of the novel, modern civilisation is destroyed.

[From the pond go down the hill, past Friends House on your left, as far as:]

8] 110 HEATH STREET

[This is on the left hand side and is easy to miss since it has a high garden wall. Look out for a red post box in the South-West corner of the wall at the end of the garden; from there you can look back and catch a glimpse of the house]

This was Catherine and Donald Carswells’ home in 1923. It was owned by Catherine’s brother, Gordon MacFarlane, who had the top floor. The Lawrences lived in a flat in the middle. Frieda came to live here in August 1923 after she had returned to England alone from New Mexico; Lawrence joined her here when he himself returned, in December 1923. During this period he hated London particularly: ‘It seems very dark, and one seems to creep under a paving-stone of a sky, like some insect in the damp. I don’t like it at all’ (4L 550). ‘London ‒ gloom – yellow air – bad cold – bed – old house – Morris wall-paper – visitors – English voices – tea in old cups – poor D. H. L. perfectly miserable, as if he was in his tomb’ (4L 546).

It was from this house that he and Frieda left to go to the famous ‘last supper’ at Café Royal, and to this house that he was brought back drunk and incapable afterwards (Murry and Carswell carrying him). It was here that he started his series of articles including ‘On Coming Home’ and ‘On Being Religious’. The house has a letter box in its end-garden-wall, dated VR (Victoria Regina) – therefore it was certainly there in Lawrence’s time. Into this he would have posted letters to Mabel Dodge Luhan, Robert Mountsier, Knud Merrild, Secker, Seltzer, Witter Bynner, Frederick Carter, Alfred Stieglitz, and Frieda’s mother Anna von Richthofen.

The garden door in the same wall was the model for the starting point of his story ‘The Last Laugh’, which he wrote in 1924:

‘A confused little sound of voices, a gleam of hidden yellow light. And then the garden door of a tall, dark Georgian house suddenly opened, and three people confusedly emerged. A girl in a dark-blue coat and fur turban, very erect: a fellow with a little despatch case, slouching: a thin man with a red beard, bareheaded, peering out of the gateway down the hill that swung in a curve downwards towards London.

“Look at it! A new world!” cried the man in the beard, ironically, as he stood on the step and peered out.

“No Lorenzo! It’s only whitewash!” cried the young man in the overcoat. His voice was handsome, resonant, plangent, with a weary sardonic touch.’ (WWRA 122:6-17)

9] FOLLOWING ‘THE LAST LAUGH’

The Murry character (named Marchbanks) and the Brett character (named James) set off down the hill, but get diverted by the laughter which Marchbanks keeps hearing, and of which he locates the source among ‘the trees and bushes inside the railings over the road’ (125:30). They go across the road, accompanied by the ‘young policeman’ (124:37).

[Cross Heath Street to a grassy island and, at the near (North) end of this island climb up the stairs to ‘The Grove’].

James and the policemen then see how Marchbanks ‘ran swiftly up the avenue lined with old trees’: this is probably The Grove, where the trees have been cut down, but their stumps and trunks can be identified. The house into which Marchbanks turns may be no. 12 or 13.

James and the policeman then return to Heath Street and keep on going down hill towards what, in 1924, Lawrence described as ‘the yellow, foul-smelling glare of the Hampstead tube station’ (WWRA 123:29-30).

[Instead, go South along The Grove and turn left into Holly Mount to see the Holly Bush pub and Holly Bush house.]

Here we leave the story for a moment and travel back in time to 1914.

10] HOLLY BUSH MOUNT: JACKSON, LOW, EDER, JONES

In the summer of 1914, Lawrence and Frieda got to know Catherine Jackson (later Carswell), Barbara Low and her circle (including the Eders, and eventually Ernest Jones) via Barbara’s niece Ivy, who had visited them in Italy.

In particular, they got on with Catherine Jackson; Lawrence used her address, Holly Bush House, Holly Mount, as his forwarding address when he went to the Lake District on 31stJuly. Also in Holly Mount, at no. 13, was Herbert Watson, reviewer of The Rainbow. The Lows lived on Holly Bush Hill.

Lawrence and Frieda met this ‘colony of new friends’ during late June and July 1914. The Murrys were jealous; Murry recorded:

‘there was to be a picnic on the Heath, and [. . .] we [Murry and Katherine Mansfield] had been specially invited. There was no help for it; obviously we must go. So on a beautiful afternoon, in late July [1914], [Gordon] Campbell, Katherine and I with the Lawrences took the tube for Hampstead. All went well until we reached the Hampstead Station. We emerged in good order, and began to advance up the steep little road immediately opposite – Holly Bush Hill. We three hung back a little, so that the Lawrences were well ahead. Suddenly there was a piercing cry of “Lawrence!” and we had a hasty glimpse of a young lady [Ivy Low], clad it seemed in a kimono, rushing with enthusiastic arms outspread down the hill. “Good God!” said Campbell, “I won’t have that!”said Katherine. With one accord we sped down the hill, round the corner, and fled’

When he returned home Lawrence was very angry, though he had to admit that no one had seen us in flight. But, as he reasonably complained, we had made him look a fool. He had turned round to introduce us, and we just weren’t there. Katherine tried to mollify him by explaining that it was not deliberately done; and that she simply had a horror of effusiveness . . . Like her own Kezia [PreludePart 3], she could not bear things that rushed at her. Moreover, there is no doubt that we were very exclusive: we had the Campbells and the Lawrences, and desired no other friends.’ (Nehls i. 233)

[Retrace your steps along Holly Mount (which is a cul-de-sac) and continue down Holly Hill; at the bottom pause to look back up, and see where Ivy Low appeared in her kimono.]

11] ‘THE LAST LAUGH’ CONTINUED

[Walk on down the Hampstead High Street, as the story demands, past the entrance to Flask Walk.]

On the way down the High Street, many entrances are of interest.

David Garnett’s friend, and Frieda’s temporary lover, Harold Hobson, lived at 3 Gayton Crescent, at the end of Gayton Road, on the left.

The next street off to the left is Willoughby Road; across the road almost opposite are a few fragments of the old yellow brickwork still visible of the old Police Station. This is where, while Lawrence and Frieda were with Dollie Radford late in 1917, they must have gone, as Lawrence recounts in Kangaroo:

‘Richard and Harriett went to a police-station for the first time in their lives. They went and reported themselves. The police at the station knew nothing about them and said they needn’t have come. But next day a great policeman thumping at Hattie’s door, and were some people called Somers staying there. It was explained to the policeman that they had already reported – but he knew nothing of it.’

(K 248:12-17).

The extant, handsome, disused red-brick police station on the corner of Willoughby Road is post-war.

Mark Gertler lived in Rudall Crescent and worked at Penn Studio, on the left up Willoughby Road, and was able to advise the Lawrences about potential lodgings in 1926. After their time on the East coast, which Lawrence had so much enjoyed, they wanted to come to London so that Lawrence could talk to the people who would be staging his play David: ‘We’d just take a place in Hampstead for a week or so’ (5L526) was how by the mid-1920s Lawrence envisaged being in London; for him, Hampstead was London.

30 Willoughby Road was the site of the Lawrences’ last Hampstead lodgings, from 16th to 28thSeptember 1926 – and of Lawrence’s last night in England. They left on the morning of Tuesday 28thSeptember for Paris, after which Lawrence wrote his first draft Lady Chatterley’s Lover, strongly influenced by having witnessed the General Strike during his visit.

Back on track on Rosslyn Hill: after the tiny entrance of Pilgrim’s Lane comes the turning to Downshire Hill; Edward Garnett had his lodgings at no. 4, which is where – after attending his sister’s wedding in Eastwood – Lawrence spent the night of 6thAugust 1913 before going to Germany on Thursday 7thAugust to meet Frieda in Irschenhausen. He then went on with her to Lerici to write The Sisters (which became The Rainbow). David Garnett’s friend and lover Anna Wickham (that was her pen name; her real name was Hepburn) lived further down, at no. 49.

[Continue further down to:]

12] ST STEPHEN’S CHURCH, POND STREET

In ‘The Last Laugh’ James and the policeman have been following this route; in 1923 there was a ‘grove of trees’ next to the church:

‘As the girl and the policeman turned past the grove of trees near the church, a great whirl of wind and snow made them stand still, and in the wild confusion they heard a whirling of sharp, delighted voices, something like seagulls, crying:

“He’s here! He’s here!”

“Well, I’m jolly glad he’s back,” said the girl calmly.

“What’s that?” said the nervous policeman, hovering near the girl.

The wind let them move forward. As they passed along the railings it seemed to them the doors of the church were open, and the windows were out, and the snow and the voices were blowing in a wild career all through the church.

“How extraordinary that they left the church open!” said the girl.’

(WWRA130:19-30)

St Stephen’s is the church wrecked by the storm of Pan in this story.

13] DOROTHY BRETT’S LODGINGS IN POND STREET

[Turn left at the Church into Pond Street.]

On the right is the Royal Free Hospital (founded 1828, but only since the 1970s on the current site). In 1923-24 Brett lodged at what was then numbered as 6 Pond Street; this is the ‘little stucco house’ (130:14) with its ‘little railed entrance’ (131:20) where James and the policeman go, and where – at the end of the story – Marchbanks returns after spending the night with the woman up the hill. Here he pitches forward and dies on the carpet. John Middleton Murry lived next door. Katherine Mansfield lived on the first floor of no. 6 from mid August to late September 1922, moving from there to Fontainebleau, where she died in 1923. Murry’s house next door belonged to the artist Boris Anrep.

[Finally, continue down Pond Street and then turn left towards Hampstead Heath Overground Station, where you can rest in one of the cafés or pubs.]