I co-edited Volume 5, Number 2 (December 2019) of the Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies with the journal’s editor Sue Reid. The theme of the edition was ‘Lawrence and London’, and it contained developed versions of a selection of the most London-orientated papers delivered at the 33rd International D. H. Lawrence Conference ‘London Calling: Lawrence & the Metropolis’, of which I was the Executive Director. I hosted this conference at my home institution of New College of the Humanities in London in July 2017. The introduction, of which the following appears in a pre-edited version, appeared on pp. 22-29. My article on Lawrence’s relationship to Russians in London during the First World War may be found here.

INTRODUCTION

For all Lawrence’s ferocious and repeated criticisms of London from 1914 onwards, it was a city to which he repeatedly returned, and with which much of his success was connected. There his teaching career reached its culmination and its termination, his literary career was launched, and his married life saw several of its crucial moments. He visited London around fifty times – initially in October 1908 for his interview for a teaching position in Croydon, and for the last time in September 1926 – when he was twenty-three and forty-one respectively. Over the intervening eighteen years he visited or lived in London in every single year apart from during his American travels of 1920-22. He saw the city grow from seven to eight million inhabitants, and accumulate buses, trams, private cars, bridges, Underground stations, West End theatres, and electric street lights. It affected him even when he was not present. In 1913 Frieda’s divorce hearing was heard there; in 1915 The Rainbow was tried at Bow Street Magistrate’s Court; in 1926 The Widowing of Mrs Holroyd was performed at the Kingsway Theatre; in 1927 David was produced at the Regent Theatre; in 1928 Catherine Carswell oversaw the typing of part of Lady Chatterley’s Lover; in the same year Lawrence explained to the readers of The Evening News ‘Why I Don’t Like Living in London’; and in 1929 his paintings were exhibited at the Warren Street gallery, before thirteen of them were removed to a police station on the grounds of obscenity. For such an intrinsically nodal city (in terms of global power, finance, and modernism), and one of such importance to his life, it occupies a somewhat peripheral place in his writings. Yet that position is nonetheless important, and was well due the scrutiny that it received at the 14th International D. H. Lawrence Conference ‘London Calling: London & the Metropolis’ (held in London 3-8 July 2017). From that conference and this associated Journal edition a picture has emerged of a city which often represented much that Lawrence abhorred, yet was also a centre of friendship and cultural production which continuously drew him back. The facts that in the spring of 1927 he both wished to come to London to oversee the production of David, and was reluctant to do so (not only on grounds of poor health); or that London was ambitious enough to produce David, but its critics reviled the result, typify this tension. Though Lawrence would never again see London after 1926, for his four remaining years he remained in intense correspondence with it as a centre of art, of publishing, and of his imagination – as can be seen in the second and third drafts of Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Croydon – his location as a schoolmaster from 1908-1912, and primary geographic focus of Joyce Wexler’s and Holly Laird’s articles – challenges the definition of ‘London’. When Lawrence wrote about ‘Dull London’ in September 1928, one can assume that he was (un)generously including Croydon in the designation. Yet it occupied a liminal position, between and within easy reach of not only the metropolis but also the surrounding countryside. As Joyce Wexler points out, from this base he was received in many of the most important locations of literary London: the Reform Club (Violet Hunt), Kensington (Ezra Pound), Bedford Square (Ottoline Morrell), and Hampstead (H. G. Wells). Later in his life, he was to live for longer or shorter periods in Kensington, Hampstead, and Bloomsbury (at the Conference, Colm Kerrigan noted the East End as being a rare and surprising exception from Lawrence’s engagement with London’s regions). But from his Croydon base he also went sightseeing to other liminal London locations, such as Hampton Court, Richmond, and Wimbledon. In her Conference paper Barbara Kearns presented him as ‘driven’ by unfulfilled lust in 1908-12 to roaming in search of love amongst, or in the vicinity of, haystacks at Epsom, Dorking, Reigate, the Cearne, and the Surrey Downs.

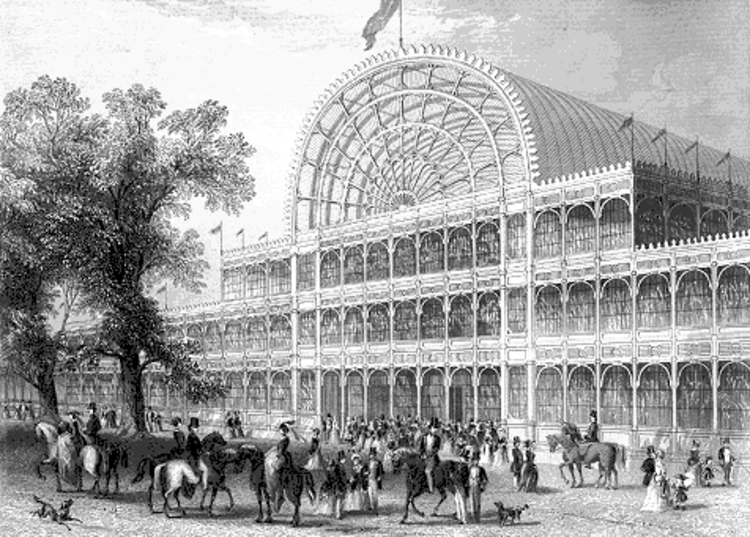

Yet it was not only in such semi-rural and rural locations that Lawrence felt in contact with nature during his time in London. Holly Laird – who identifies an increasingly sharp focus on London in the revisions of Lawrence’s Croydon poems during the War and again for the 1928 Collected Poems, and who presents him as ‘a new London poet’ – argues that for him London was no simple way allied with the machine or industrialism. On the contrary, she demonstrates how Lawrence departed from a tradition of English poetic descriptions of London that had started with James Thomson’s ‘City of Dreadful Night’ (1874), since for him ‘the city is transformative, and urbanization is rarely set in opposition to nature; on the contrary, they mingle’. In contrast to Fyodor Dostoevsky, whose Winter Notes on Summer Impressions (1863) featured the Crystal Palace as the embodiment of soulless rationalism, he envisions the Palace positively in ‘A Still Afternoon’. He also turns to natural metaphors in describing his close attention to the bodies of the homeless sleepers in ‘Embankment at Night, Before the War: Outcasts’. Stewart Smith (like Terry Gifford at the Conference) points out the urban nature presented by Aaron’s Rod, in which Bloomsbury Square is perceived ‘like a savage wilderness in the heart of London’ (AR 69).

London’s limits are porous not only with regard to geography but also demography. As Jane Stafford quotes Ford Madox Hueffer as saying, London was ‘a ragout of titbits’, ‘a permanent world’s fair’, ‘a great slipshod, easy going, good-humoured magnet’.[i] Lawrence himself commented, soon after his arrival in 1908, that ‘the people in London do not feel so strange; they are folk who have come down the four winds of Heaven to this center of convergence of the Universe; people in Manchester and Stockport and the awful undignified provincial towns are like races of insects running over some food body; one naturally gravitates to London; one naturally flees from the cotton centres’ (1L 80). Joyce Wexler and Jane Stafford describe how Lawrence was encouraged as a provincial writer on London’s literary scene, whilst Stafford also draws out the parallels between this and Katherine Mansfield’s reception as a colonial exotic. She points out that although both negotiated London’s modernist financial marketplace adroitly, it became a stable home for neither. At the Conference, Masashi Asai compared Lawrence’s and Japanese novelist Soseki Natsume’s experiences of London (the latter’s in 1900-2), and underlined the difficulties that both faced as outsiders.

Yet Lawrence benefitted greatly from London’s function as a ‘magnet’. Lee Jenkins, in her study of Aaron’s Rod as the first of an autobiografictional cluster of novels published between 1922 and 1960, points out that ‘H. D.’s set’, ‘more cosmopolitan, perhaps, than its Bloomsbury other’, ‘had its origins in the transatlantic avant-garde’. Aaron’s Rod presents London as a staging post for its protagonist between provincial England and Europe, as it so often served for Lawrence himself. The current author links Lawrence’s contacts with revolutionary and tsarist Russians in London before, during, and after the 1917 Russian revolutions to his developing politics, and to his interest in a country which his writing presents as an extreme marker of cosmopolitanism.

Such cultural variety was part of what thrilled Lawrence about London in his early years. Towards the end of ‘Dull London’ he declares: ‘Twenty years ago, London was to me thrilling, thrilling, thrilling, the vast and throbbing heart of all adventure. It was not only the heart of the world, it was the heart of the world’s living adventure’ (LEA 120-2). Such ‘living adventure’ resided for him also in the city’s artistic culture. On his arrival 1908 wrote to Jessie Chambers: ‘Truly, there are meetings, and, better, theatres and concerts’ (1L 96). As Joyce Wexler describes, his career was launched by such luminaries of the London literary scene as Ford Madox Hueffer and Edward Garnett, who saw his potential early and invested in it despite the fact that his first three novels all raised potential legal problems; they taught him much about how to negotiate the financial and legal realities of a writing career. London was also Lawrence’s first big city. As Stewart Smith points out, it remained for him throughout his life ‘privileged’ ‘as a reference point when evaluating unfamiliar urban centres’ (such as Milan and Mexico).

However, Lawrence’s attitude towards London underwent a sudden shift in response to the First World War, the spiritual corruption of which Lawrence felt to have taken particular hold there. In May 1915 he wrote to Ottoline Morrell:

We were in London for four days: beautiful weather, but I don’t like London. My eyes can see nothing human that is good, nowadays: at any rate, nothing public. London seems to me like some hoary massive underworld, a hoary, ponderous inferno. The traffic flows through the rigid grey streets like the rivers of Hell through their banks of dry, rocky ash. The fashions and the women’s clothes are very ugly. (2L 339)

Eight years later, in Kangaroo, Somers reminisces: ‘In the winter of 1915-1916 the spirit of the old London collapsed, the city, in some way, perished, perished from being a heart of the world, and became a vortex of broken passions, lusts, hopes, fears, and horrors.’ (K 216) Lee Jenkins notes that the trauma of War is registered after the event by the writing and setting of Aaron’s Rod in the early twenties, despite being based on events which took place during it. She also notes this traumatised ‘repetition compulsion’ to be manifested in the other three later novels (by John Cournos, Richard Aldington, and H. D.) which she compares to Aaron’s Rod.

By 1924, in his ‘Dear Old Horse, A London Letter’, Lawrence’s wartime visions of London quoted above persist in slightly modulated form, without the ‘vortex of broken passions, lusts, hopes, fears, and horrors’: ‘London is awful: so dark, so damp, so yellow-grey, so mouldering piecemeal. With crowds of people going about in a mouldering, damp, half-visible sort of way, as if they were all mouldering bits of rag that had fallen from an old garment’ (MM 137). He contrasts London to New Mexico – a contrast recapitulated in St Mawr in the following year. This critique was taken further, as Stewart Smith points out, in the 1928 essay ‘Dull London’, which Smith characterizes as presenting nihilism, mass culture and hedonism as threats both to individuality and to dynamic connectedness. On the one hand, War trauma persists: ‘Evoking London’s proximity to the First-World-War battlefields, Lawrence observes that the London traffic “booms like monotonous, far-off guns, in a monotony of crushing something, crushing the earthy, crushing out life, crushing everything dead”’ (LEA 121). On the other, just as Holly Laird observes that Lawrence’s early poetic characterisations of London deviated from those of James Thomson, Stewart Smith observes that even in his later work he deviated from Charles Dickens’s presentation of London as a place suffering, by criticizing ‘the idealisation of the values of “Nice, safe, easy” that serves to produce a collective state of deadening numbness’ (LEA 121). He observes that Kate Leslie in The Plumed Serpent is deterred from returning to England from Mexico by the thought of ‘buses on the mud of Piccadilly … I may as well stay here, where my soul is less dreary’ (PS 439-40). Lawrence’s own brief return to London in 1923-4, which included his failed bid to recruit several of his friends to his projected community of ‘Rananim’, may have informed the hardened presentation of London in the final version of the novel as compared to Quetzalcoatl. A similar hardening of stance took place between the first, and successive, drafts of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. In the second draft:

In London, at the theatre or at people’s houses or even in the street, she [Connie] felt the whole influence of all the people dead against her own rhythm … London was far, far worse than the Midlands, than Uthwaite or Tevershall, in spite of the ugliness of these latter. The noise of London, and the endless chatter, chatter, chatter of the people seemed like a death’s-head chattering its teeth in a sort of cold frenzy. So many dead people! So many dead ones, masquerading with life! (FLC 482)

In the final draft of 1928 the comparison is not with the provinces, but abroad: ‘In Paris at any rate she felt a bit of sensuality still. But what a weary, tired, worn-out sensuality’ (LCL 254). This passage goes on to criticize Paris as ‘One of the saddest towns: weary of its now-mechanical sensuality, weary of the tension of money, money, money, weary even of resentment and conceit, just weary to death’. As Ginette Katz-Roy outlined in her speech at the British Council in Paris this May, Lawrence was consistently critical of that city. The same had not been true of London. In his response to no other thing can the depressive influence of the War on Lawrence be traced more clearly than in his response to London. And yet, as all the essays which follow will demonstrate, complexities in his relations to the world’s biggest city always remained.

[i] Ford Madox Hueffer, The Soul of Modern London (London: Dent, 1905), 20.