Eva Joly, French Green MEP and former prosecutor

Monday 3rd February 2020, 5.30-8.00 pm in St Pancras New Church, Euston Road, London, UK

Organisers:

Deepa Govindarajan Driver (University of Reading)

Iain Munro (University of Newcastle)

The following account is based on the notes that I took at the event. It is not a word-perfect transcription. To the best of my belief it is not materially incorrect, but I would welcome any corrections sent to catherine@catherinebrown.org.

It was written at the invitation of, and is published with the approval of, the event’s organiser, Deepa Driver (@deepa_driver).

The views expressed are the speakers’ own. I reproduce them in order to express support for the event, for Julian Assange, and for Wikileaks.

For further materials concerning Julian Assange on this blog, please see my write-up of:

Free the Truth, Thursday 28th November, 2019, 5.50-8.30 pm in St Pancras New Church, Euston Road, London, UK, with speakers Lowkey (rapper), Lissa Johnson (clinical psychologist), Fidel Narvaez (former Ecuadorian consul), Lisa Longstaff (of Women Against Rape), Mark Curtis (historian and journalist), Nils Melzer (UN Special Rapporteur on Torture), Craig Murray (former UK ambassador, now human rights activist), and John Pilger (investigative journalist).

This write-up contains, at the bottom, general background information on the case.

Also:

‘Imperialism on Trial’, 11th and 12th June 2019, St James’s Church, Clerkenwell, London, with speakers including Vivienne Westwood (fashion designer), Chris Hedges (Pulitzer Prizewinner), Clare Daly (Irish TD and MEP), Ogmundur Jonasson (former Icelandic Interior Minister), and myself (on the subject of character assassination).

and

‘Imperialism on Trial’, 1st May 2019, Bloomsbury Baptist Church, London, with speakers including Kristin Hrafnsson (the Editor-in-Chief of Wikileaks), Annie Machon (former-MI5 officer), and Peter Ford (former UK ambassador to Syria).

The speakers at ‘Free the Truth’ on 3rd February 2020, were Craig Murray (former UK ambassador, now human rights activist), John Shipton (father of Julian Assange), Eva Joly (former French prosecutor, Green EU parliamentarian and member of the Development Committee), Lisa Longstaff (Women’s rights campaigner and spokesperson for Women Against Rape), and Nils Melzer (UN Special Rapporteur on Torture),

CRAIG MURRAY

‘Julian’s case is extraordinary. The fact is that he is up for extradition on charges of espionage for publishing the truth about war crimes. The fact is that this is the most political charge you can imagine, and he’s being [potentially] extradited under an extradition treaty that starts off by barring political cases. I can’t find a precedent of anyone being given as long as Julian was given for bail-related charges. Jack Shepherd killed someone, ran away and hid, and on his return to Georgia was given half the sentence that Julian was given. We had in the original Swedish extradition case the Supreme Court ruling that Julian’s extradition request was valid even though it didn’t come from the right authority, a prosecutor, because the French not the English legal text of a treaty permitted this. This is the only example of this occurring. Judicial exceptionalism has existed at every stage of the process of the abuse of Julian Assange.

Many of you here have heard me speak about Julian and his case many times. I would like to give a different perspective today – the perspective of a whistleblower. Julian is a publisher; he is not a whistleblower; he didn’t leak any government secrets. I am a whistleblower. I had a career of 21 years in the Foreign Office, including 6 in the senior management structure, and when I came across UK complicity in torture and extraordinary rendition I decided that I couldn’t go along with it. As the government were denying that extraordinary rendition existed – Jack Straw said it was a conspiracy theory – I realised that I would have to produce evidence to get people to believe me. I leaked a number of government documents. The first and most important was published by The Financial Times.

When I did that, I was well aware that I was taking the risk that if I was caught I would go to prison. My main tactic was not to get caught. But of course, if you are someone like me who had been in government, who had access to secret material, then deciding as a matter of conscience not to keep secret material secret – of course you know you may go to jail. I was prepared to. I could paper my walls with letters from the FCO threatening to prosecute me under the Official Secrets Act. I always said ‘I am at home if you wish to arrest me’.

The reason nothing happened – I know this for certain, not a matter of conjecture; I have friends in that organisation – was because of a man called Clive Ponting. You may remember him – he leaked the evidence that the Belgrano was sailing away from not towards the Falklands at the time that it was sunk. Ponting was prosecuted under the Official Secrets Act. There is no doubt that he was guilty. But the jury refused to convict. Because 12 honest citizens refused to send a man to prison for telling the truth about a war crime. And in my case I know that Jack Straw decided they could not prosecute me because they might get a Clive Ponting verdict, which would undermine the Official Secrets Act, and give more publicity to their complicity in torture and rendition.

Assange’s case is as though they had prosecuted the then-editor of The Financial Times. That would be the death of a free media if it is allowed to happen. Journalists do their job. I leaked further supporting material. I had meetings with a number of journalists. They were asking me to give them more documents. That is the job of a journalist. There is malice in the case against Julian Assange. We live in difficult times. Fifteen years ago I leaked the intelligence material on torture and extraordinary rendition. Today they would prosecute in a secret court. The public would not be admitted; nobody would be allowed to report; because it would be a security case. There would be no jury, only a judge. The freedom that allowed Clive Ponting to get away – that has been destroyed by the security apparatus that has stripped away freedoms in the name of the war against terror. We must see the attack on Julian Assange in the light of the broader attack on civil liberties. That is why it is essential we stand with him. His extradition must be stopped. And we must try to hang to a freedom fighter, the right to publish material, and the right of citizens to know about the crimes of governments.’

JOHN SHIPHTON AND SEVERINE

There are so many familiar faces here. I have to say that they are friends, or extended family, that I’ve met over the years of this fight for Julian’s freedom.

I’d like to make two points.

First, the institutional policy of judicial abduction is a policy put in place over the last ten years by the US rewriting extradition laws with all countries that would accede. My country Australia has sent five people to the US. This parallels their policy of extrajudicial murder, such as we saw the other day in Iraq. These events are no accidents. The intimidation that weighs on all journalists, publishers and publications, after witnessing the persecution – and, to quote Nils Melzer, ‘the slow murder of Julian Assange’ – means that we won’t get any insights into government, we won’t have verifiable factual information to understand the policies and directions of governments so that we can decide whether to support these programmes or to manifest against them.

Second, Julian has never broken any laws. Over the last ten years he has sought the laws of the countries concerned to be on his side. Yet he is incarcerated in Belmarsh maximum security prison for now eleven months (forgive me if I’m inaccurate), twenty-two hours a day staring at the ceiling, unable to have access to his lawyers, or a computer to defend himself. The extradition request must be cancelled. I live here now and I’m renting a house. His sister [Severine] lives with me, who you’ve just met. His brother is a British citizen, as are his nephews and cousins. He should be given bail to be at home with his family.

PROFESSOR EVA JOLY

Only a massive mobilisation of ordinary people and people from the legal community can stop Assange’s extradition. Because it has been programmed for years that he should be extradited.

He shouldn’t be, first of all for legal reasons. It is a basic principle of extradition that the alleged crime must be a crime in both of the countries concerned. Publishing information that is of public interest is not a crime in the UK. There is no evidence the Julian Assange has penetrated the system of the American army. So the US is trying to get him extradited on charges of violation of espionage act. If we let that happen, we allow the US to have extraterritorial competence, meaning it is for the US to decide what is contrary to their security interests. That we cannot have – where they can decide what we can publish. We have seen it in other areas: today there is very powerful anti-corruption legislation. This law, which we in France have not resisted, if such that if an American interest is involved, the US takes the case. So a corruption case in France involving dollar transactions will be prosecuted in the US. This has been a terrible weapon that has been used against European industry. When you look at the cases in which it has been used, you can see that it is a political tool.

There is another condition for extradition, which is that one is sure that there will be a fair trial. In this case we are sure of the contrary, because of what Trump and Hilary Clinton have said. So we know that he is hated, and we know that he was spied on in the Ecuadorian embassy, and that he has been denied the fundamental right to have a private conversation with his lawyer. The most extraordinary thing is that the Spanish company that did the spying had a direct link to Donald Trump. The situation has been very difficult since the beginning because of the reputation of Sweden as the home country of human rights. That reputation pertains to a long time ago. As a member of European parliament, I have participated in enquiries into secret CIA prisons in Europe (Poland and Romania), and the secret flights to and from these prisons. They stopped at Swedish airports with the permission of the Swedish government.

I want to go back a bit, to how I came to understand this case. I happened to meet Assange when we were both in Iceland, I in relation to the banking crisis, and he to create a haven for journalists in Iceland. We met to try to set that up in 2009. When I later discovered that he was in the Ecuadorian embassy, I thought that my duty was to go and see him. I came to understand that something was very wrong because the Swedish prosecution authorities, who claimed that it was not possible for their prosecutor to go to London to meet with Assange. I knew, as a prosecutor, that this is bullshit – that is a perfectly ordinary practice. I thought that I had to go and tell her. And I did. I did press conferences. I said that this is not normal. That was a very strong signal that something was wrong. At that time I didn’t know if it was US manipulation. She should certainly have been taken off the investigation, as she had made a huge error. That didn’t happen. Why? It turns out that the CPS dissuaded the Swedes from interviewing Assange in London. This is not an ordinary extradition case; it is a political To the UK authorities – we are watching you. If you dare extradite Julian Assange, it is to your dishonour.

LISA LONGSTAFF

Julian Assange and Chelsea Manning are being persecuted by states for leaking information about murder, rape and torture, in Iraq, Afghan, Bosnia and elsewhere. Soon after the leaks, there appeared allegations of sexual offences against Julian Assange in Sweden. From 2010 we at Women Against Rape have pointed out the unusual zeal with which they pursued the case against him. We said from day one that it was for political reasons. On the one hand the women were railroaded by the prosecutors; their names were all over the press. The women are not in charge of the case – the state is. The CPS told Sweden not to drop the cases. Men making cases about false rape charges does not help Assange’s case, especially amongst women. Assange has been treated by the media as though he were guilty.

Generally when women report rape, the investigations are negligent; you’re supposed to report online and wait to be contacted; in 2018 the Metropolitan Police were successfully sued for failing to investigate John Warboys, despite their £1 million legal appeal against this. Typically, women drop out of the system, for example because their phone and social media are trawled and passed to the defence. Fewer than three percent of rape trials end in conviction. So don’t tell me that the UK cares about rape.

We at Women Against Rape oppose rape, torture and the death penalty, but the people who want to torture Assange are defending rapists, torturers and murderers. When in 2004 we wrote to female MPs about the rape that was taking place during the Iraq war, not one answered. We refuse to let women’s rage at the injustice that exists around rape to be used to persecute whistleblowers or journalists.

NILS MELZER

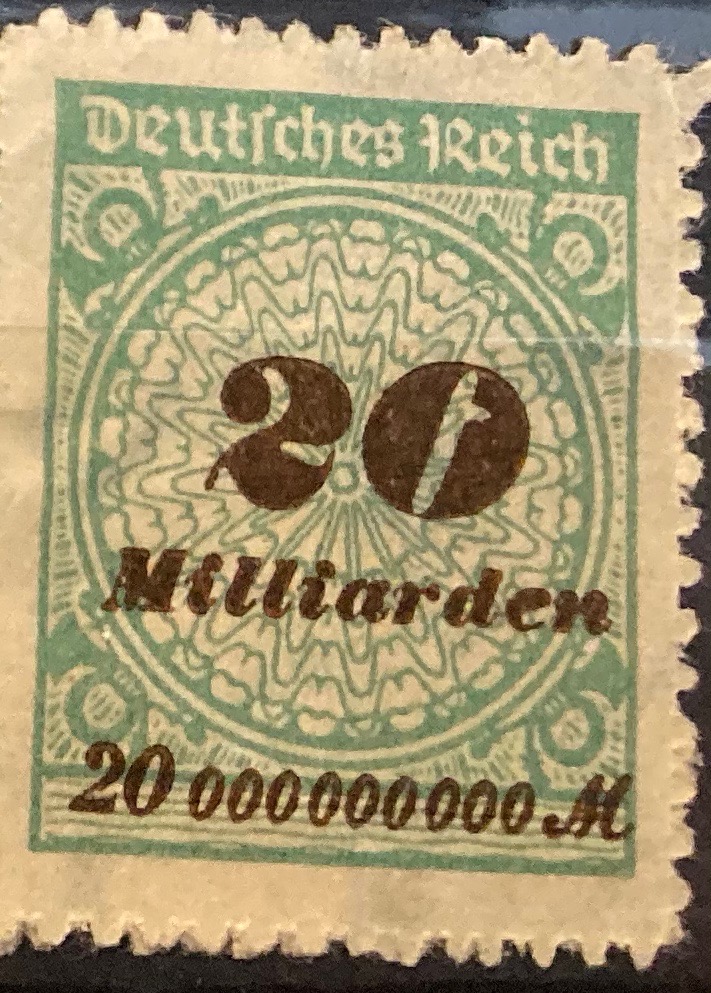

Two hundred years ago we decided that we no longer wanted governments to have absolute power. We want them to be subject to the rule of law. So there was an end of absolutist rulers, and the creation of democracies and the separation of power between the judiciary, legislature and executive. They are supposed to control and balance each other.

But we have a problem. The human factor. Humans are not by nature democratic. Uncontrolled power will be abused; our knowledge of this is based on the painful experience of centuries. We are now at critical point. The modern system is prone to collusion between ministers, MPs, and lobbies. To control that collusion we have the press. And that is what this case is about. We need a free press that holds the organs of power to account, and to make sure they are checking and balancing each other rather than colluding. This is what we are risking losing when imprisoning people who tell the truth that is no longer told to us by the press.

I started on this case last April. I thought that it would be very short. I thought that I will go and do a few medical tests on him; I did not expect to find much.

What I found was very different. I found a man who had been hunted for a decade. I found documents that proved profound corruption in the judicial system. The deeper I went the more I was shocked. I don’t say that there is no rule of law in the countries concerned in cases that don’t threaten the main power. But as soon as that power is threatened, we do not have the rule of law. I investigated this case. Of course it was related to torture – Assange revealed torture that was not investigated and prosecuted. And he was himself hunted for years and subject to intense, deliberate investigation; that is torture. That’s why women get raped on the village square – everyone needs to be intimidated. That is what is happening here. Someone is being tortured before our eyes. The message is: if ever you dare to publish information, this is what will happen to you. And this is where we have to say stop.

I have to report to states. I reported. The states did not then do their job. They refused to do their job. They say I lost my impartiality. Am I supposed to be impartial between a torturer and a tortured? I have to be impartial when investigating. But once I have found that someone has been tortured, of course I am not neutral. This man has never killed anyone, yet he faces 175 years in prison.

Some human rights organisations refuse to recognise him as prison of conscience, but even they recognise that his conditions in the US would be inhumane. I expect a response of Sweden and Britain. The Foreign Office says that the UK does not condone or practice torture. But when the UK parliament reported in 2018 that it was involved in USA torture, the government refused to investigate. They also flatly refused even to discuss the torture findings that two independent medical doctors found of in the case of Assange.

The Foreign Office is currently running a high-profile campaign for press freedom, but they detain Europe’s most famous political prisoner just a few miles away from their conference, and don’t even mention him.

I am still waiting for a response. More than 100 days after I sent an urgent appeal to the UK government because I was afraid for Assange’s life, the complained about me; the UK ambassador in the US told me that they are not happy. I refuse to be intimidated. I am fighting for the UK people. It is time for the UK people to hold their government to account and to use their institutions to do so.

We thought that it would be good idea to organise a debate tomorrow at Chatham House, the Royal Institute for Foreign Affairs. Suddenly Chatham House cancelled. Isn’t that striking? In 2020, the 100th anniversary year of Chatham House, celebrating a century of ‘independence’ (according to their website), they have cold feet. Happily the Front Line Club has stepped in [the event did indeed take place on 4th February 2020 at the Front Line Club]. Have we forgotten about the Chinese dissident who found refuge in US embassy in Beijing? There are many examples of refugees taking refuge in embassies. What is the difference for Assange? How far have we sunk? If we prosecute people for war crimes for exposing war crimes. War criminals in the Hague are sentenced to just 40 years for genocide – but Assange faces 175.

QUESTION AND ANSWERS

Asked about the Harry Dunn case, Craig Murray commented that it is important in its own right: ‘Anne Sacoulas [who accidentally killed the British teenager Harry Dunn with her car] and her husband never had diplomatic immunity. Under the Vienna Convention this is only for diplomatic agents. The Convention specifically says that immunity for family members only applies to those holding diplomatic rank, which does not pertain in this case. Mr Sacoulas was an intelligence officer who was not based at any embassy. It was simply a lie when his place of work was designated as part of the US embassy. The UK domestic legislation refers to the Vienna Convention explicitly. I am fed up because what’s happened is that Anna Secoulas was whisked out of the country with the connivance of the Foreign Office. The government has been pretending ever since to pretend to get her back. This is another example of the ignoring the rule of law. That is why we shouldn’t make any equivalence of the two cases [this and Assange’s]; the two are absolutely separate.

Asked about Roy Greenslade’s recent article in support of Assange in The Guardian, Deepa Driver said that we should be grateful for it. Lisa Longstaff commented: ‘about bloody time; The Guardian has treated Assange appallingly; it has been one of the major perpetrators of a lot of the lies.’

Asked about the relevance of the US election cycle, Craig Murray commented that ‘these cases can take years. The authorities are keen to extradite. But it could take a while. It’s no secret that there’s quite a gulf between Trump personally and his security services. I retain a hope that we one day see a presidential intervention in order to stop this farce, which I don’t think has been driven from the White House. We have an election coming up. We must all hope and work towards a refusal of the extradition at the first days at Westminster. But having been in the Court and seen what’s happening I think that’s extremely unlikely. I don’t think for a moment that the magistrate is acting as an independent judge; I can’t see that magistrate standing up to the powers that be. If Trump were to be re-elected then whether at that stage a president who’s got re-elected might be able to intervene in the process I don’t know. If Sanders is elected there may be hope. With Biden I doubt it. Do I think this case will last beyond the next election? Yes I do.

Eva Joly added: ‘I don’t think that a change in the presidency would change anything. I remember what Diane Feinstein said. She has been hard on the CIA and secret prisons, but she was also very hard on Assange. I think our only hope is that the British do their job. Extradition is a statement. The judiciary are giving an opinion. I think we have to fight for the judiciary to say no. That is what the law says they should do.’

Lisa commented that we should ‘commend the prisoners who have campaigned against Assange’s isolation [he was recently removed from solitary confinement after a campaign for this by his fellow prisoners at Belmarsh]. It was a huge victory. If the prisoners can do that, what can we do?’

Nils qualified: ‘I have been very disillusioned in the last year. I know that Assange is out of isolation, and I’m very grateful for that. I’m not so enthusiastic about the motivations. I don’t believe that the government doesn’t listen to the UN, but that it does listen to inmates. Good for the inmates – but I fear that it is preparation against the potential argument that Assange is not fit to stand trial. Let us be cautious.

A question was asked about the Council of Europe’s resolution last week about media freedom – to what extent was it political, and did it have any legal ramifications? Nils Melzer answered that: ‘it’s not a binding resolution, but I do think it is very important. In the last six months good things have been going on. In Germany people in parliament, not just on the left, but also an associate of Merkel, have spoken out against Assange’s extradition.’

A question was asked about the international reach of the campaign in support of Assange. It was noted that an international campaign had been very successful during the first imprisonment of Chelsea Manning. Eva Joly commented that she had recently written an article in Le Monde blaming journalists who had benefitted from information provided by Wikileaks but did not defend Assange. She could not get that same article published in Sweden, and knew that it would be impossible here in Britain. The situation, she commented, was better in France, Germany and Switzerland.

Of the smear campaign against Assange Nils Melzer commented: ‘If you’re in a dark room with one person moving a spotlight around, you look at what it illuminates. That’s the media. They are telling us where to look. We have to know that the room is much bigger, and that we might be missing the elephant in it. Wikileaks takes the spotlight and points it at crime. So the other side takes it and puts it onto something else – allegations of rape, cruelty to a cat, excrement on the walls. The war crimes are then not being prosecuted.

Asked whether the show trials of the 1930s and 40s were repeating themselves, Nils Melzer said that history should not repeat itself, given the existence of modern technology: ‘now we should react as we should have reacted in the 30s.’

Craig Murray added: ‘when I was in Westminster Magistrate’s Court [for a previous hearing in the Assange case], we were all behind one screen of bullet-proof glass and Assange was behind another. It was all completely unnecessary. There was no security reason for this; it was a demonstration of the power of the state; that is what show trials were used for. But the work goes on: after this event I’m meeting with Wikileaks about publishing some more secrets. The Council of Europe decision was a very good, strong statement. And there have been other good signs. I used to get a lot of abuse online when I wrote in favour of Assange; that has much lessened now; people are gradually working it out. Even The Guardian. Behind the scenes progress is being made with some MPs that you might be surprised about. The work everyone is doing at every level is extremely important. It is a fight we can win.’