SECOND MEETING REPORT

THE RED-TROUSERED PHILOSOPHER: D. H. LAWRENCE AND THE REVOLT INTO STYLE

STEPHEN ALEXANDER

Thursday 24th October 2019

New College of the Humanities, 19 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3HH

6.30-8.30 pm

ATTENDERS

Stephen Alexander

Tom Bonneville

Catherine Brown

Jessica Curry

Pat Hopewell

Alex Korda

Christian Michel

Anthony Pacitto

Sofia Pelendridis-Roberts

Hugh Stevens

Lara Taylor

[Lawrence wrote the essays ‘Insouciance’ and ‘Red Trousers’ in 1928 for the Evening News; the first was published in July under the editorial title ‘Over-earnest Ladies’, and the second in September as ‘Oh! for a New Crusade’. ‘Insouciance’ was written in the Grand Hotel on Lake Geneva. It describes him looking from his hotel balcony out over the landscape and at two mowers scything. His absorption is interrupted by an elderly Englishwoman on the next balcony, whose conversation soon involves ‘the Signor Mussolini. Before I know where I am, the little white-haired lady has swept me off my balcony, away from the glass lake, the veiled mountains, the two men mowing, and the cherry-trees, away into the troubled ether of international politics.’ ‘Why […] does the little-blue eyed lady resolutely close her blue eyes to them all [‘mountains, lakes, scythe-mowers and cherry-trees’], now she’s got them, and gaze away to Signor Mussolini, whom she hasn’t got, and to fascism which is invisible anyhow? Why isn’t she content to be where she is? Why can’t she be happy with what she’s got? Why must she care?’ Lawrence thinks that she would do better to ask the older, fatter of the mowers why he wears black trousers unlike the blue cotton ones of the younger. ‘Red Trousers’ archly admires the activity involved in modern crusades (‘Votes for women, or teetotalism, or even the Salvation Army’), but deplores the dullness that attends these crusades’ success. Men are in any case running out of crusades to go on, so ‘The thing to do is to decide that there is no crusade or holy war feasible at this moment, and to treat life more as a joke, but a good joke, a jolly joke. That would freshen us up a lot. Our flippant world takes life with a stupid seriousness […] It is time we treated life as a joke again, as they did in the really great periods like the Renaissance. Then the young men swaggered down the street with one leg bright red, one leg bright yellow, doublet of puce velvet, and yellow feather in silk cap’. The 20-line poem ‘A Sane Revolution’, one of the Pansies, was written later in 1928, and enjoins ‘If you make a revolution, make it for fun’.]

Stephen Alexander used ‘Insouciance’ and ‘Red Trousers’ as the basis for an exposition of Lawrence’s meta-ethic of insouciance, which he explicitly related to Oscar Wilde’s valorisation of surface over depth, Nietzsche’s concept of superficiality arising from profundity, anti-puritanism (‘the puritan is disconcerted by fashion, its insouciance’), and dandyism. However, although ‘dandy has no objectives’, he ‘is resistant’, and has his own kind of discipline. Stephen acknowledged that Lawrence saw the wearing of red trousers as ‘a solution to the class system’, and that as such his dandyism was involved in, rather than abstracted from, politics.

He went on to observe that ‘in recent years’ the wearing of red trousers – twice praised in Lady Chatterley’s Lover – has become less acceptable in England, partly because of class envy, partly because of residual homophobia (dandyism having been associated with homosexuality ever since the Wilde trial), and, more recently, anti-hipster sentiment (hipsters having adopted them) – especially outside of London, in places such as Eastwood. Yet red trousers featured strongly on the catwalk in 2019, and a (mildly satiric) blog is devoted to photographs of ‘RTs’ being worn today: http://lookatmyfuckingredtrousers.blogspot.com

Christian Michel placed red trousers in historical contrast to the dark, sober men’s clothing that had developed during the nineteenth century, and internationalized it by observing that until 1914 the French army had blue jackets but red trousers. Catherine suggested, in response to the former point, that advocating men’s returning to the colourful clothing of the 18thC and previously might have been a crypto-feminist move on Lawrence’s part, because advocating equality of self-decoration between the sexes. Stephen countered that if anything, Lawrence was reversing rather than equalizing permissible self-display between men and women.

He found a continuity of dandyism between the two essays, whereas Catherine found a rupture between the praise in ‘Insouciance’ of what we would now call ‘mindfulness’, and the later essay’s doctrine of flippancy. She questioned the idea that the latter was, in any case, representative of Lawrence’s last phase, containing as it did the Last Poems as well as the Pansies such as ‘A Sane Revolution’, and the authoritarianism of the ‘Introduction’ to The Grand Inquisitor as well as the insouciance of ‘Red Trousers’.

Hugh Stevens thought that Lawrence was not, in fact, being at all insouciant when he wrote about insouciance; in fact, he was in a decidedly bad temper. Stephen agreed that Lawrence repeatedly tried to be light-hearted and gay, but always collapsed back into emotional intensity; a similar contradiction could be seen in the fact that in ‘A Propos of Lady Chatterley’s Lover’ Lawrence criticizes the fetishization of underclothing, yet himself indulged in this, amongst an entire A-Z of other fetishes. But Hugh responded with the distinction that Lawrence’s thoughts on red trousers concern the pleasure of the wearer, not that of the viewer (Captain Hepburn resists his objectification as layers of cloth, in Hannele’s fabric doll of him). Stephen responded that the contradictions in Lawrence, as in Nietzsche, indicate that there is no core, or substance, under the surface. Sofia Pelendridis-Roberts questioned whether he meant this. Stephen replied that he did, and that under such circumstances, being a dandy – as Sebastian Horsley argued – is a defense against the suffering of life.

Hugh’s observation that the mention of Piccadilly in ‘Red Trousers’ doubtless had reference to the fact of its connection with rent boys and aesthetes led to a discussion of Lawrence’s sexually-active, or would-be-active, early life in London; this was reprised in a late discussion, initiated by Alex Korda, of Lawrence’s under-representation of contraception in his fiction. Stephen added that Lawrence’s obsession with nakedness tips the balance against clothes, but Hugh observed that Lawrence could also object to nakedness, as he does to that of women in ‘Fig’. This led to a consideration of Angela Carter’s essay ‘Lorenzo as Closet Queen’, which was generally agreed to have been tinged by homophobia, and which Stephen criticized as condemning precisely that which it might have celebrated.

Finally we considered what application these thoughts might have to the present – for example, ‘Insouciance’ as a recommendation of mental self-protection from the stresses of Brexiting Britain. Lara Taylor suggested that the ‘revolution for fun’ was itself exemplified by those who voted for Brexit in order to set the cat among the pigeons. Opinions different as to whether XR – which had been highly active in central London soon before the meeting – consisted of large numbers of young people engaging in something in part ‘for fun’, or whether the movement was in fact ascetic. Stephen argued that ‘the revolution’ had already happened; all that follows is ‘a game of masquerade’. Alex Korda responded that ‘the revolution hasn’t yet started’.

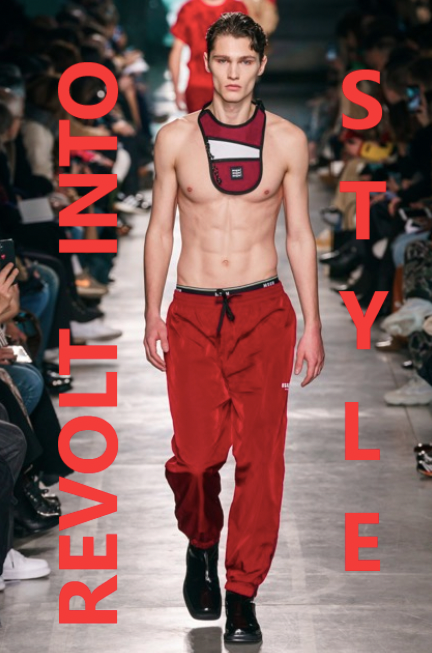

One question left unanswered was whether the fashion industry (represented by the four photos below) is insouciant – or whether it does not, rather, take itself ‘in deadly earnest’.

Stephen Alexander

is a London-based philosopher-provocateur, born in Paris in May 1968. He has a Ph.D. in Modern European Philosophy and Literature from the University of Warwick. He has written several books; some of which are out of print, some of which unpublished. He blogs at torpedotheark.blogspot.co.uk

Abstract

Perhaps because, as Roland Barthes suggests, “they alone are sufficiently free from its perceived triviality,”[1] some of the most interesting writings on fashion have tended to come from our poets and novelists, including Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Wilde, and Proust. I would also include D. H. Lawrence on this list and find it rather surprising that more critical attention hasn’t been paid to this aspect of his work, particularly as it relates to questions to do with gender, sexual identity, and the manner in which we inscribe signs of culture upon the flesh.

In this short paper, I will discuss Lawrence’s neo-dandyism and the associated ethos of insouciance, arguing that the young men Lawrence imagines strolling along the Strand dressed in red trousers have recognised the Wildean truth that in all matters of importance, style and an ironic, carefree indifference, not sincerity, is what matters.

Revised Paper

- Opening Remarks

Although in ‘Red Trousers’ Lawrence spends most of his time writing about the need for a new crusade or adventure in order to counteract what he perceives to be modern dullness, he comes to the conclusion that this isn’t feasible any longer and that the only thing to do, therefore, is curb our enthusiasm and treat life as a joke.

For ultimately, says Lawrence, dullness is rooted in moral seriousness. He thus picks up a theme from an earlier article in which he complains about being forced to care in an ideal manner about abstract issues and not allowed to live happily in the moment, observing real people and speculating on actual events.

We should, he suggests – though doesn’t actually use the term in the text itself – be a little more insouciant. I’ll say more about this shortly, but would like first to read the crucial closing section of ‘Red Trousers’:

“It is time we treated life as a joke again, as they did in the really great periods like the Renaissance. Then the young men swaggered down the street with one leg bright red, one leg bright yellow, doublet of puce velvet, and yellow feather in silk cap.”

Now that is the line to take. Start with externals, and proceed to internals, and treat life as a good joke. If a dozen men would stroll down the Strand and Piccadilly tomorrow, wearing tight scarlet trousers fitting the leg, gay little orange-brown jackets and bright green hats, then the revolution against dullness which we need so much would have begun.”[1]

Lawrence describes this revolution against dullness in one of the Pansies as a ‘sane revolution’.[2] But we might also call it a revolt into style …

- Revolt into Style

In an age of terror and impending global catastrophe, there is nothing for it but irony, indifference, and insouciance. What we really don’t need right now is a greater degree of earnestness. For fanaticism is always marked by its moral sincerity and is, as Wilde pointed out, the world’s original sin: “If only the caveman had known how to laugh, history might have been different.”[3]

Fashion, above all else, is a passion for artifice. This, coupled to its love of empty signs and cycles, is what most alarms the puritan in his grey suit and sensible shoes, rather than its overtly erotic element. For in our culture, tethered as it is to a principle of utility and meaning, the fact that fashion is futile and pointless – and prides itself on such – means that those who like to dress up and mess up are always going to be branded immoral.

Thus, the queer young men imagined by Lawrence, cruising through Soho in brightly coloured clothes for no good reason in the middle of the afternoon, may well be sexually disconcerting to some, but this is secondary in comparison to the outrage they cause because of their perceived flippancy, flamboyance, and aristocratic disdain for the world of work.

Their “sailing gaily, in brave feathers”[4] and refusal to care about the ideal abstractions of metaphysical philosophy, or the latest news report concerning a celebratory they’ll never meet, a weather event they’ll never experience, or a killer virus they’ll never suffer from, is what I understand by the phrase ‘revolt into style’. A transpolitical revolt that teaches us to become superficial out of profundity and to understand that society and self are both founded on cloth.

Of course, some might object that such a ‘revolt’ is vacuous and a form of conceit; that by promoting the figure of the dandy rather than the worker, Lawrence diverts attention from the political realities of the world with its oppressive social relations and violent power structures. Elisa Glick, for example, can’t help showing her Marxist roots when she asserts that the dandy’s revolt against modernity is nostalgic, elitist, and pessimistic; a wilful exchanging of history for hopeless fantasy which is why he ultimately ends by “losing himself in the alienation and reification of modern metropolitan life”.[5]

To be honest, as a lover of Dorian Gray and Patrick Bateman, this is not really a concern for me and terms such as ‘alienation’ and ‘reification’ seem laughably naive and old-fashioned – particularly when found in the vocabulary of someone who should know better. I would suggest that a sense of feeling estranged is crucial to the very queerness of Lawrence’s writing and so too is a lapsing out of personal identity into the happy state of the object.

Having said that, Lawrence does, in his fiction, seem to view the wearing of red trousers as part of the solution to class struggle – Mellors famously writing to Connie:

“‘If the men wore scarlet trousers […] they wouldn’t think so much of money: if they could dance and hop and skip, and sing and swagger and be handsome, they could do with very little cash.’”[6]

That’s certainly a debatable claim. But what’s interesting is how Lawrence isn’t merely concerned with clothes and bodies, but with the manner in which the logic of fashion – its promiscuity and playful indeterminacy – begins to effect what Baudrillard terms the ‘sphere of heavy signs’ and by which he refers to the realm of politics, morals, economics, science, culture, and sexuality. It’s when this happens, that’s there’s panic on behalf of those who like to take these things (and themselves) very seriously indeed.

Baudrillard writes:

“Beyond the rational and the irrational, beyond the beautiful and the ugly, the useful and the useless, it is this immorality in relation to all criteria, the frivolity, which at times gives fashion its subversive force (in totalitarian, puritan or archaic contexts) …”[7]

Anticipating Baudrillard, Lawrence recognises and delights in the fact that – as I said earlier – what most alarms the puritan about fashion is not the very obvious erotic element, but its carefree character.

Young men in red trousers annoy moralists on both wings of the traditional (but now redundant) political spectrum, not because they seem overtly threatening or dangerous, but because they blatantly prefer art, pleasure, idleness, and cosmopolitan decadence above the manly (and bourgeois) values of industry, rationality, and national chauvinism. The dandy stages a transpolitical provocation beyond all rationality; his is “a resistance without ideology, without objectives”[8] – a revolt into style.

III. Insouciance

The dream of the Enlightenment was that everyone would become so politically well-informed – or woke, as some now like to describe it – that they would be incapable of being ignorant of or indifferent towards anything. But it seems that the smartest individuals and most interesting artists – like Lawrence – invariably choose to remain carefree and “avoid the mortal danger of being concerned”.[9]

In the article ‘Insouciance’, Lawrence concludes that so many people are consumed with concern that there opens up at last a “deadly breach between actual living and this abstract caring”[10]. He thereby anticipates the postmodern fate of those individuals who, having fallen out of touch with ‘life’, become trapped in the ‘real-time’ world of 24-hour news and social media, worrying about the so-called climate emergency, etc.

Ultimately, Lawrence’s notion of insouciance might be conceived as a form of Nietzschean gaiety; a way of thinking that delights above all in the happiness of language; a form of radical thought is never boring or overly serious, but is, rather, playful and poetic, ironic and ambiguous.

- Red Trousers

The traditional view is that men and women wear clothes for three reasons: firstly, to cover up their nakedness; secondly, to protect them from the elements and, thirdly, for purposes of ornamentation. But Barthes sees this as a restricted (and restrictive) reading. For him, dress is most important as a signifying activity:

“The wearing of an item of clothing [– such as red trousers –] is fundamentally an act of meaning beyond modesty, ornamentation and protection. It is an act of signification and therefore a profoundly social act at the very heart of the dialectic of society”.[11]

Unfortunately for Lawrence and those who share his penchant for red trousers, there has been something of a backlash against them in recent years and wearers are routinely scorned online and abused in public. In a YouGov poll in 2013, only a minority of people questioned thought it ‘acceptable’ for grown men to wear red trousers and many found them ‘offensive’. In fact, the findings suggest that just 12% of the UK population overall think positively about men with scarlet legs.[12]

Why? What underlies this sartorial prejudice? Partly, of course, it’s class envy: red trousers have long been associated with toffs and members of the ruling class. But it also betrays a certain homophobia as one of the first words that came to people’s minds when seeing a man in bright-coloured trousers was not ‘posh’ but ‘gay’ (followed by terms including ‘twat’, ‘clown’ and ‘wanker’).

Lawrence was wise, however, to suggest his dozen dandies strolled through London, as YouGov found that Londoners were marginally more inclined to appreciate them than citizens of other towns and cities in the UK. Red trousers probably wouldn’t go down well in Eastwood (I say this as someone who was jeered at in a local pub for asking for ice in my gin and tonic). In fact, only 10% of people in the Midlands were found to be red-trouser positive.

According to one commentator,[13] this negative reception of red trousers only really picked up steam when hipsters began wearing them and found themselves featured on the now dormant blog look at my fucking red trousers! This blog – created by Monsieur Henri de Pantalon-Rouge – claimed to be celebrating the ‘vibrant and burgeoning red-trousered communities’ but it was, of course, gently mocking them at the same time and encouraging others to do so, as the following statement makes clear:

“From South Ken to Shoreditch, from Jermyn Street to Mare Street – these days anyone that’s anyone is wearing red trousers.

If you want your leg-coverings to let the world know that you’ve got a few quid and don’t care who knows it, or that you have some big ideas about what’s on at the ICA right now – or simply that you are completely insane […] – then you’d better get your wife or girlfriend to take those jeans and chinos down to the charity shop post-haste!

Because there’s only one type of trousers you’ll be wanting to wear, and that’s RED TROUSERS. In fact, if you can’t wear red trousers you’d be better off wearing NO TROUSERS AT ALL.”[14]

Whatever the cause of their unpopularity and fall in sales, the issue was deemed serious enough in 2016 to be addressed in Country Life[15] and The Telegraph, both publications doing their best to reassure its readers that red trousers were nothing to be ashamed of and had an important place within British fashion history.[16]

Probably best, however, that Lawrentians keep their red trousers at the back of the wardrobe for a while and consider other colours; such as bright cornflower blue, for example. Though of course, as Lawrence notes, it has always taken courage to “sail gaily, in brave feathers, in the teeth of dreary convention”[17] and so if you want to continue wearing your red trousers, don’t let me persuade you otherwise.

- Afterword

One of the wonderful things about fashion is that it rapidly and constantly changes – and Lawrentians will be pleased to hear that red trousers are suddenly back in vogue and can be seen in numerous collections on the catwalks in 2019, including …

MSGM (Fall 2019 Menswear Collection)

Dries Van Noten (Spring 2019 Menswear)

Roberto Cavalli (Fall 2019 Ready-to-Wear Collection)

Paul Smith (S/S 2019)

Emilio Pucci (Spring 2019 Ready-to Wear Collection)

Stephen Alexander (2019)

torpedotheark.blogspot.co.uk

[1] D. H. Lawrence. ‘Red Trousers’, Late Essays and Articles, ed. James T. Boulton, (Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 138.

Of course, I would radicalise Lawrence’s position and suggest not only that we start with externals, but that we remain there too; for there are, in fact, no internals to which we might proceed. Outer form or appearance is not expressive of inner essence or substance and things have no concealed reality; the secret of life is that it has no secret. Dandyism is a critical ontology and philosophical ethos which, according to Foucault, can be characterized as a ‘limit-attitude’ beyond the dualism of inside-outside.

As for Lawrence’s colour combinations, they’re a bit too much for me I have to admit, although they would have delighted Oscar Wilde who wrote: “There would be more joy in life if we could accustom ourselves to use all the beautiful colours we can fashioning our own clothes. The dress of the future, I think, will […] abound with joyous colour.” See ‘The House Beautiful’, in the Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, (Harper Collins, 1994), p. 923.

[2] D. H. Lawrence, ‘A Sane Revolution’, The Poems, ed. Christopher Pollnitz, (Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 449.

[3] Oscar Wilde, ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’, Complete Works, p. 43.

[4] D. H. Lawrence, ‘Red Trousers’, Late Essays and Articles, p. 138.

[5] Elisa Glick, Materializing Queer Desire: Oscar Wilde to Andy Warhol, (SUNY Press, 2009), p. 30.

[6] D. H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, ed. Michael Squires, (Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 299.

[7] Jean Baudrillard, Symbolic Exchange and Death, trans. Iain Hamilton Grant, (SAGE Publications, 2007), p. 94.

[8] Ibid., p. 99.

Think of Marlon Brando in The Wild One: when his character, Johnny, is asked what it is he’s rebelling against, he notoriously replies with theatrical masculine bravado that is both posing and performative: ‘What’ve you got?’ This is not to deny, however, that the dandy has an interestingly ambiguous relation to capitalism; one that is not only rebellious, but also in some sense complicit, as Elisa Glick demonstrates in Materializing Queer Desire.

[9] Jean Baudrillard, The Conspiracy of Art, ed. Sylvère Lotringer, trans. Ames Hodges, (Semiotext(e), 2005), p. 37.

[10] D. H. Lawrence, ‘Insouciance’, Late Essays and Articles, p. 97.

[11] Roland Barthes, ‘Fashion and the Social Sciences’ in The Language of Fashion, trans. p. 97.

[12] Findings of the YouGov poll are discussed by Haley Dixon in an article in The Telegraph (31 July 2013) entitled ‘Red trousers are officially a fashion faux pas, YouGov poll finds’.

Visit: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/howaboutthat/10214101/Red-trousers-are-officially-a-fashion-faux-pas-YouGov-poll-finds.html

[13] Guy Kelly, ‘Look at my f***ing red trousers: How one blog ruined the ultimate upper-class fashion statement’ The Telegraph (3 March 2016). Visit: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/men/style/look-at-my-fing-red-trousers-how-one-blog–ruined-the-ultimate-u/

[14] Henri de Pantalon-Rouge : http://lookatmyfuckingredtrousers.blogspot.com/

[15] Flora Watkins ‘In defence of red trousers’, Country Life (4 March 2016). According to Ms Watkins, red trousers are worn by “decent, upstanding chaps with names such as Giles or Henry, the sort whose heads are hard-wired to leap to their feet when a lady enters the room” and display a charming English eccentricity. Visit: https://www.countrylife.co.uk/country-life/in-defence-of-red-trousers-83921#ae87U03LfjJiJugl.99

[16] The Telegraph editorial was entitled ‘Should men ever dare to wear red trousers?’ (2 March 2016): https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/12181284/Should-men-ever-dare-to-wear-red-trousers.html

[17] D. H. Lawrence, ‘Red Trousers’, Late Essays and Articles, p. 138.