Report of the Twenty-Fifth Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

SHIRLEY BRICOUT WITH CATHERINE BROWN

DAVID PLAY READING

Friday, 16th December 2022

By Zoom

18.30 onwards UK time

ATTENDERS

17 people attended, including, from outside of England, Shirley Bricout in Vannes, Brittany,

Justin LaPoint in North Carolina, Kathleen Vella in Malta, and Jim Phelps in South Africa (until an apparently not-atypical failure of the national power company obliged him to leave early).

INTRODUCTION

This was to have been a hybrid event, with people gathered at Catherine Brown’s home in London as well as joining by Zoom. A train strike put paid to the physical aspect, so the meeting was as usual purely on Zoom. Lawrence’s play David was available here for those who didn’t have a hard copy. Shirley Bricout, following on from her presentation on Old Testament patriarchs earlier this year, introduced the figure of David, Lawrence’s play about him, and each of the selected scenes which we read together.

DAVID PLAY READING

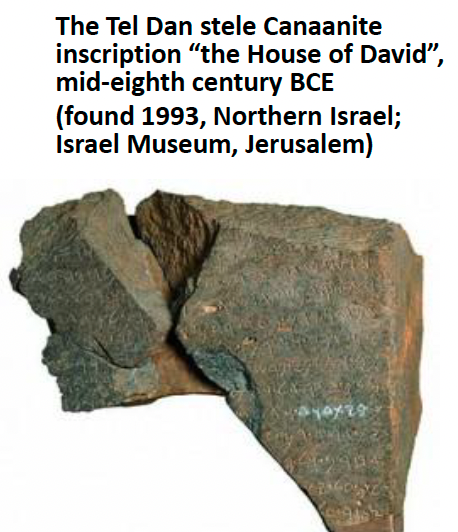

Shirley introduced David as he appears in the Jewish scriptural/Old Testament books of Samuel, Kings and Chronicles. He is supposed to have lived around the turn of the 11th-10th centuries BC, to have displaced his erstwhile patron Saul who had lost God’s favour (aided by his best friend, Saul’s son Jonathan), to have united Judah and Israel and to have established a temple cult at Jerusalem. Yet he himself eventually lost God’s favour by acting treacherously in order to gain Bathsheba as a wife, and was therefore not allowed to complete the Temple in Jerusalem, this task falling to his son Solomon. In part due to the attribution of the Psalms to him (though these were probably written over five centuries, with only the earliest belonging to David’s time), he is associated with musical gifts, and in particular the lyre. There is some – though not much – archeological evidence for his existence.

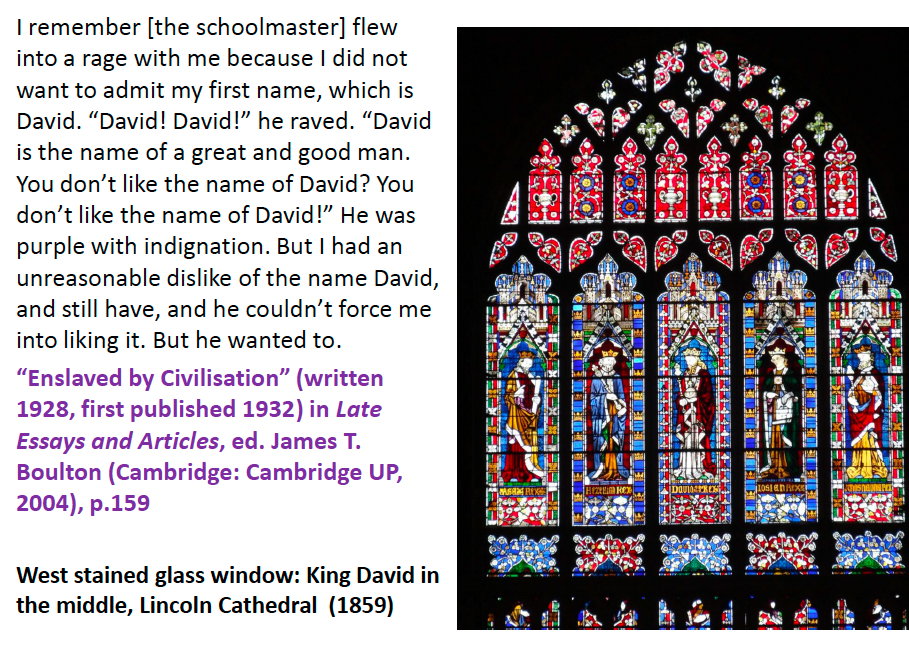

Lawrence was highly conscious of having the same name as this Israelite King:

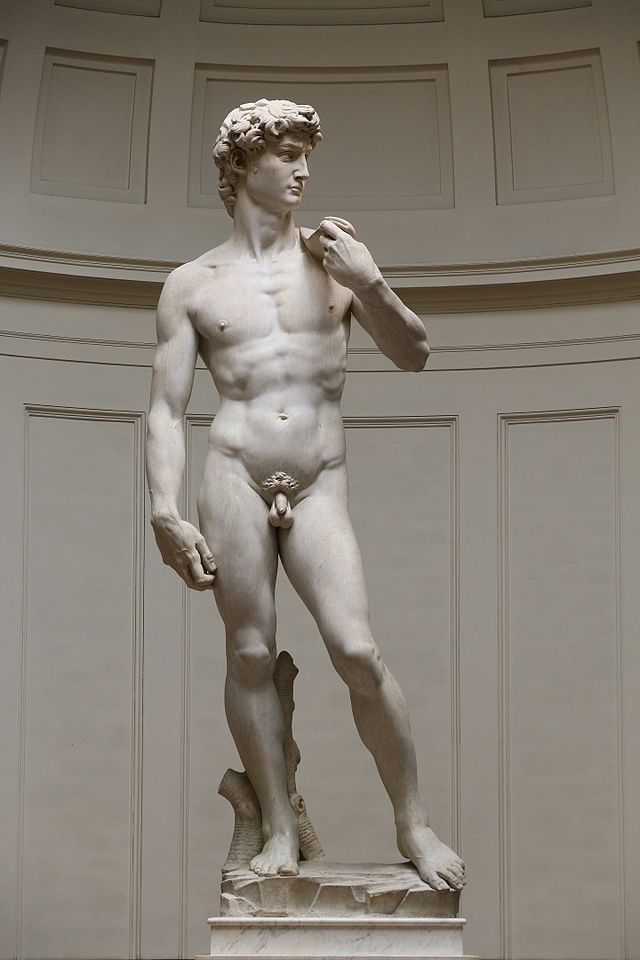

David is represented several times in the stained glass of Lincoln Cathedral. He wrote several times about the sculpture of the shepherd Goliath-slayer made by Michelangelo in 1504:

In the spring of 1925, whilst travelling in Mexico and New Mexico, and between bouts of illness, Lawrence wrote the sixteen scenes of his play David. Frieda had been reading the Bible during the trip, and suggested the idea of a Biblical play; she then translated the resulting play into German. It was first performed in 1927 at the Regent’s Park Theatre in London; though Lawrence, who was living in Florence, did not attend. It had a disappointing reception. There were further performances in Cambridge, England, in 1933, in Los Angeles in 1938 (with Frieda and Aldous Huxley present), in Cambridge in 1958, and at the University of Nottingham in 1996.

The play opens with Saul being berated by the prophet Samuel for having disobeyed God by not having completed the massacre of his vanquished enemy the Amalekites; it ends with Saul’s son Jonathan supporting David in escaping from Saul, who now recognises him as his rival.

Drawing on John Worthen’s interpretation of the play as set out in his Cambridge University Press edition (Plays Part 2, CUP, 1999), Shirley argued that Lawrence presents David’s conception of God as a personal God, whereas Saul’s conception is more cosmic (and, as such, influenced by the American religions that Lawrence was discovering at the time of writing). She explained that the songs sung in the play (including a few actual Psalms) were put to music by Lawrence; his scores are reproduced on pp 587-601 of the CUP volume. This music, too, has Indian rhythms (though in the 1927 premiere Lawrence’s music was replaced by that of Richard Austin, and Lawrence’s music was not to be performed until the 1996 University of Nottingham performance).

Together we read all or part of five scenes from the play – 2 (in which the prophet Samuel, in a monologue that replaces the Biblical dialogue with God, prays and painfully resolves to find a replacement for Saul), 4 (in which Samuel in Bethlehem recognises David as the son of Jesse who has been chosen by God to become King), 5 (in which David and Jonathan discuss Saul’s fall from grace and affirm their friendship), 7 (in which David volunteers and manages to slay the Philistine champion Goliath), and 15 (in which Saul acquiesces wildly in his downfall whilst a chorus of prophets chants; this scene was cut entirely in the first performance). Shirley pointed out the Hebraic patternings and repetitions of the language, which she discusses also in her chapter on the Bible in The Edinburgh Companion to DH Lawrence and the Arts, ed. Catherine Brown and Sue Reid).

Those who were willing to read volunteered for parts, which changed between scenes. John Worthen memorably read David delivering his animistic ‘whirlwind’ speech, Goliath meeting his nemesis, and Saul becoming mad. Jim Phelps read Jonathan, Jane Nichols read the David who slew Goliath, whilst Justin LaPoint was the onlooking Saul. John reminded us that at one stage Lawrence had decided to name the entire play Saul.

THE DISCUSSION

There was much admiration expressed for the poetry of the play’s prose. John Worthen thought that it would make a great radio play if heavily cut. Catherine Brown thought that Lawrence had given David an easy ride; the balance of the play’s sympathies might be delicate, but the Biblical accounts give grounds for a far more critical understanding of David than the play offers. John responded that this was a function of the play concentrating on David’s early life, and that it is not clear what his path thereafter will be. He thought that Lawrence’s attempt to contrast Saul’s cosmic faith with David’s quest for a personal God did not ultimately succeed, but that it was a great attempt, in the manner of The Plumed Serpent. John and Shirley agreed that Scene 15, in which Saul becomes mad, is a great one, but Shirley observed that within the play we never see Saul actually in touch with his cosmic God. John noted that Lawrence places a considerable explanatory burden on Samuel. With regard to dramaturgy, Catherine admired the offstage handling of David and Goliath’s combat in Scene 7, which is watched by an onstage audience, therefore resembling the climactic scene of Ibsen’s 1892 play The Master Builder.