Three women who loved Lawrence

Dorothy Brett, Frieda Lawrence, Mabel Dodge Luhan

1938, New Mexico

A couple of years ago I was giving a lecture series on Lawrence at Oxford University. A retired Professor came up to me at a drinks party and said, in some surprise: ‘So you’re the Doctor Brown that’s lecturing on Lawrence. But you’re a woman!’ He went on to say that I was the first person to have done a full series of Lawrence lectures since he had done it, decades before.

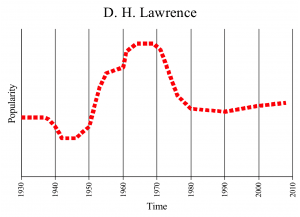

You can get some context for these comments from this:

His reputation had a bit of a dip during the war, then shot up over the fifties and sixties. This was partly because working-class men, now going to university in larger numbers than ever before, took the working-class, aristocrat-marrying Lawrence as a role-model. There was a craze for Lawrence-beards. ‘If these was one person everybody wanted to be after the war, to the point of caricature, it was Lawrence’ (said the critic Raymond Williams).

Then in 1960, Penguin’s unexpurgated edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover was famously and unsuccessfully prosecuted for obscenity. Lawrence became the poster-boy of the sexual revolution, and a working-class Priest of Love.

Neither decade had been distinguished for feminism. The backlash came in the seventies, with so-called ‘second-wave’ feminism (‘first-wave’ was the suffragettes). In 1970 Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics attacked Lawrence for misogyny and phallocentrism (behaving as though the world revolves around penises). The feminist critique knocked Lawrence off his Priest-of-Love pedastal, since when he hasn’t nearly managed to clamber back on. That’s why the Professor was surprised I was lecturing on Lawrence…

Was Millett right?

Well, second-wave feminism was long overdue, and so was a feminist critique of Lawrence. His feminist characters don’t come off well. Alliances between sisters or female friends are usually broken up by one or more men entering the scene. Lesbianism is a dead-end. In The Plumed Serpent an Irish woman more or less submits to a patriarchal Aztec cult. ‘The Woman Who Rode Away’ climaxes in a naked white woman ritually sacrificed by Native American men. In ‘St Mawr’ a spiritually-bored wife becomes obsessed by her stallion’s maleness. Lady Chatterley’s Lover complains about his wife for bringing herself to orgasm after he’d come himself. There was male triumphalism, as well as working-class aspiration, in the Lawrence cult.

BUT

There are many buts.

First – the baby got thrown out with the bathwater. Even if Lawrence was as much of a misogynist as his strongest critics claim (and he wasn’t), he would still be richly worth reading – for his descriptions of flowers, mountains, and tortoise orgasms, for his urgency about the things that matter most, and for his humour (don’t listen to those who say he had none).

Second – it helps to understand his background. He had a possessive, adoring mother, and a robust, combative wife. This resulted in some conflict, especially as he felt his virility wane. He kicked against the pricks – especially during the first half of the 1920s. It doesn’t make it more likeable; it does make it more understandable.

Third – a case should be made for Lawrence as a feminist. Women are more often than not his central characters. He often writes about girls; hardly ever about boys. His heroines – like his wife – are strong, by any standards in twentieth century fiction; submissive women are only ever minor characters. When they argue with their partners, as they often do, they give as much as they argumentatively get. Mr Noon‘s narrator says about the hero (who ressembles Lawrence): ‘he had found his mate and his match. He had found one who would give him tit for tat, and tittle for tattle.’ His women have sexual appetites, and orgasms, and sex before and outside marriage; they are presented without fetishisation or disapproval; such women had never been seen in English fiction before. Female virginity, which was such a crucial value in fiction before Lawrence, meant nothing to Lawrence. What mattered to him were profound sex and meaningful connection between people who are, somewhere, each other’s mates and matches. He loathed the way his period sexualised women. He would also have loathed the promiscuity for which he became a poster boy in the 1960s..

Fourth – he intimately described women’s lusts, fears, appetites for life, in part because he was himself in some ways womanly. As a boy he played with girls; as a man he had lots of female friends; he was weak; he did the housework; he had a feminine eye – obvious everywhere in his fiction – for men and for clothes. Contemporary women, such as the eroticist Anaïs Nin, felt that he had described their situation amazingly well.

Fifth – it isn’t always the case that when a writer is being most unlikeable, their writing is at its weakest; but the rule works pretty well for Lawrence. His most male-orientated works include some of his weakest, whereas The Rainbow, Women in Love, ‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’, ‘Sun’, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover are all centrally about strong female characters trying to find their path in life.

Sixth – many critiques of him (and lots of praise of him too) have underestimated how complicated he is. He loved contradiction: ‘all life and splendour is made up out of the union of indomitable opposites’ (Mr Noon). He uses ‘male’ and ‘female’ metaphorically; he says that all people are both male and female. His recurring idea of ‘impersonality’ is a vision of a realm beyond gender.

Today, many women write, positively, about Lawrence. It’s now obvious that the Lawrence attacked in the seventies was, in part, the version of him constructed by male adoration.

There’s lots to love in Lawrence, if you’re a lover of nature, a seeker after God, someone scared of death, someone struggling with the relationship between love and lust… Or a woman.