Report of the Thirty-Fifth Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Robert Bullock

The Rest of the Road to Vence: Lawrence’s Final Journeyings December 1928-March 1930

Friday 31st May 2024

By Zoom

18.30-20.00 UK time

ATTENDERS

28 people attended, including, from outside of England, Robert Bullock in Paris, Philip Chester in Deep River, Ontario, Shirley Bricout in Vannes, Brittany, Jim Phelps in Cape Town, Shanee Stepakoff in Essex, Connecticut, Nils Hedstrand in Munich, Monserrat Morera in Barcelona and Tim Gupwell in Perpignan, France.

INTRODUCTION

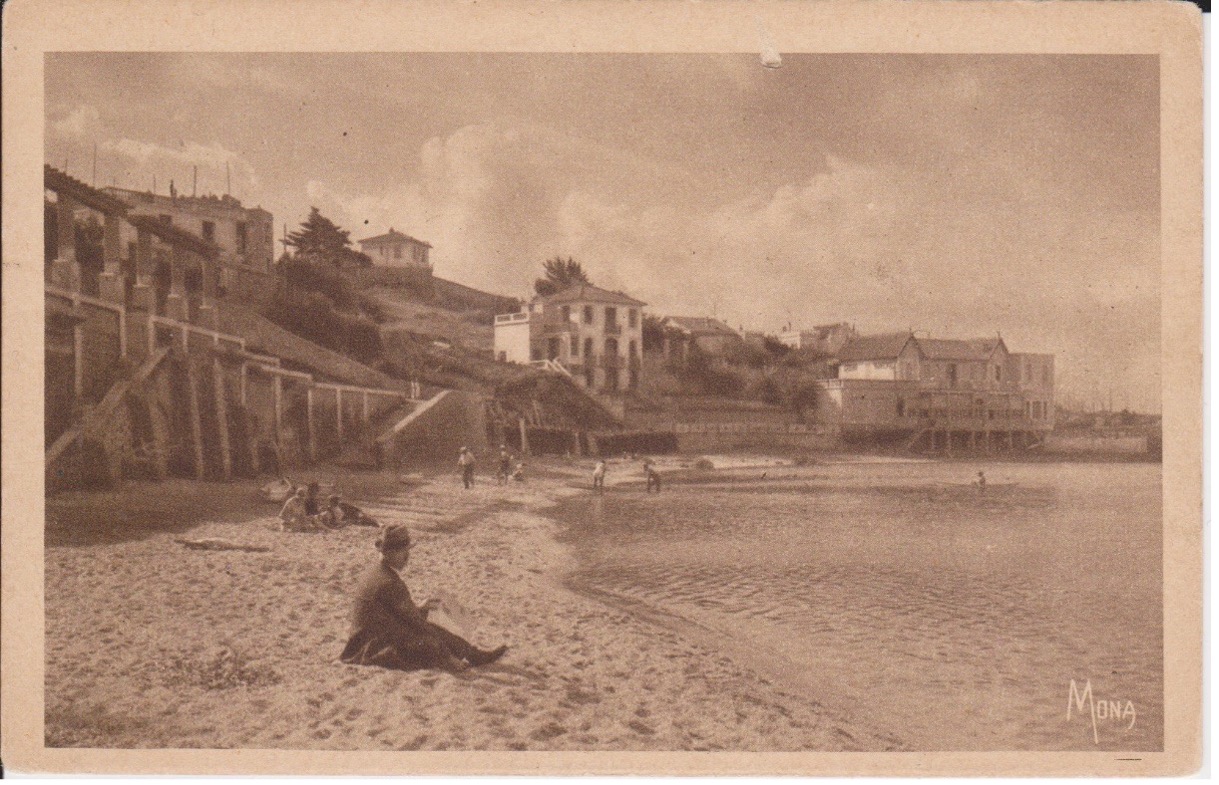

This talk was a successor to The Road to Vence Part 1 1928-1929, which Robert Bullock delivered to the London Lawrence Group on 25th May 2023. Like that talk, this one was based on the biography that Robert is in the process of writing concerning the last two years of Lawrence’s life. The present talk took us from Bandol to Paris to Barcelona to Mallorca to Forte-dei-Marmi to Florence to Baden-Baden to Bühl back to Baden-Baden to Rottach-am-Tegernsee to Bandol and finally to Vence and its Villa Robermond where Lawrence died. But the talk was also arranged thematically, in order to ‘throw light on some of Lawrence’s contradictions, convictions, prejudices, hatreds, intuitions and political and religious opinions during the last two years of his life.’ It was illustrated by pictures and by quotations on the themes, taken from Lawrence’s letters and the memoirs written about him by family, friends and acquaintances.

BIOGRAPHY

Robert Bullock is a retired teacher of English as a foreign language living near Paris. He has written various articles about Lawrence for the D. H. Lawrence Society’s [hyperlink] newsletter, Bandol town’s monthly magazine, and The Riviera Reporter, an English language magazine for the Anglo-American community in the South of France. He has successfully campaigned for the placing of commemorative plaques to Lawrence’s stays at the Hôtel Beau Rivage in Bandol (2006), the former site of the Ad Astra sanatorium in Vence (2015) and the Grand Hôtel de Versailles in Paris (2019). His biography about the last two years of Lawrence’s life is currently two-thirds complete.

READING

David Ellis, D. H. Lawrence: Dying Game, CUP 1998, pp. 451-537.

Frieda Lawrence, Not I, But The Wind …, Heinemann 1935, pp. 267-76.

Earl and Achsah Brewster – Reminiscences and Correspondence, Martin Secker 1934, pp. 193-233 and pp. 303-11.

Brenda Maddox, D. H. Lawrence: The Story of a Marriage, Simon & Schuster 1994, pp. 453-83.

Harry T. Moore, The Priest of Love, Heinemann 1974, pp. 459-504.

PRESENTATION

Robert started by thanking David Ellis (who present in the meeting) for the great help his biography D. H. Lawrence: Dying Game had given him.

‘The curious bearded man on the plage was somehow electrically dangerous; he bore a high voltage of life.’ Rhys Davies’s Print of a Hare’s Foot, p. 144

For Bandol Robert’s theme was ‘Money and the Business of Life’. In 1928 Lawrence’s income increased considerably with the succès de scandale of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, revenue from Lawrence’s many essays and articles for the British press, and his arrangement of deluxe editions of his book of paintings and of the unexpurgated volume of poems Pansies. He somewhat shamefully invested some of his surplus income on the New York stock market, since he despised the love of money, and wrote to Charles Wilson in December 1928:

The whole scheme of things is unjust and rotten, and money is just a disease upon humanity. It’s time there was an enormous revolution – not to install soviets, but to give life itself a chance … We want a revolution, not in the name of money or work but of life – and let money and work be as casual in human life as they are in a bird’s … it’s time the whole thing was changed, absolutely … You’ve got to smash money and this beastly possessive spirit. I get more revolutionary every minute, but forlife’s sake … What we want is life and trust: men trusting men, and making living a free thing, not a thing to be earned. But if men trusted men, we could soon have a new world, and send this one to the devil.

Men, alert men, should neither live nor work for money. Men must work to produce the food , warmth and shelter we all need … The rest is the great game of living.

The real activity of life is the great activity of the developing consciousness, physical, mental, intuitional, religious – all-round consciousness. This is the real business of life … All that other affair, of work and money, should be settled and subordinated to this, the great game of real living … so that we really become men, instead of remaining the poor, cramped, limited slaves we are.

But we must first wring the neck of the money bird, and settle the simple question of food, warmth, and shelter.

For Paris, the theme was ‘Vulgarity and Prudishness’. The Lawrences stayed for Easter with the Crosbys at the Moulin du Soleil, the American couple’s home north of Paris. There Frieda was delighted to discover Bessie Smith’s risqué song ‘Empty Bed Blues’, whereas Lawrence was angered by it to the point of smashing the record over her head. Lawrence was considered priggish by many of his friends; he particularly abhorred the junction of sex with humour. In December 1928 he wrote to Ottoline Morrell:

About ‘Lady C.’ – you mustn’t think I advocate perpetual sex. Far from it. Nothing nauseates me more than promiscuous sex in and out of season. … God forbid that I should be taken as urging loose sex activity. There is a brief time for sex, and a long time when sex is out of place … Old people can have a lovely quiescent sort of sex, like apples, leaving the young quite free for theirsort.

For Mallorca the theme was Politics and Politicians. Lawrence closely followed the news of the May 30th, 1929, General Election, which resulted in the defeat of Baldwin’s Conservatives and returned a hung parliament shared by MacDonald’s Labour and Lloyd George’s Liberals. Lawrence’s sympathies were with Labour. He detested Lloyd George, having described him in a letter to Amy Lowell of December 1916 as ‘a clever little Welsh rat, absolutely dead at the core, sterile, barren, mechanical … God alone knows where he will land us: there will be a very big mess.’

For Forte-dei-Marmi the theme was Doctors and Medicine. Lawrence had a long-standing distrust of doctors and medicine, and a corresponding belief that he knew best how to treat himself. Robert observed that he may have been put off medicine by his fellow consumptive and childhood friend Gertie Cooper’s traumatizing operation of 1927. Aldous Huxley despaired of getting Lawrence to accept treatment, writing to Robert Nichols in August 1929: ‘How horrible this gradually approaching dissolution is – and in this case especially horrible, because so unnecessary, the result simply of the man’s strange obstinacy against professional medicine.’ By contrast Frieda, in Not I, But the Wind… (1935), thought that ‘medicine did not help Lawrence. His organism was too frail and sensitive … How gallantly he tried to get better and live ! He was so very clever with his frail failing body … one could learn from him how to handle this complicated body of ours, he knew so well what was good for him, what he needed, by an unfailing instinct, or he would have died many years ago …’

For Florence the topic was England and the English. After thirteen of his paintings were seized from Warren Gallery on grounds of obscenity in the summer of 1929, his contempt for his home country reached a pitch, expressed in scathing terms. In a letter to Maria Huxley of August 1929 he wrote: ‘You hear the pictures are to be returned to me, on condition they are never shown again in England, but sent away to me on the Continent, that they may never pollute that island of lily-livered angels again. What hypocrisy and poltroonery, and how I detest and despise my England. I had rather be a German or anything than belong to such a nation of craven, cowardly hypocrites. My curse on them!’

For the period in which Lawrence stayed in Baden-Baden, Bühl, and Baden-Baden again, Robert’s topic was Germany. Over his acquaintance with it he had developed empathy and sympathy with it, particularly during its hard post-War years. However, just as his 1924 ‘Letter from Germany’ was prophetic concerning future developments in Germany, so too concerns that he expressed in letters in the late 1920s. In July 1929 he wrote to Orioli:

The Germans are most curious. They love things just because they think they have a sentimental reason for loving them … They make up their feelings in their heads, while their real feelings all go wrong. That’s why Germans come out with such startling and really, silly bursts of hatred … And that’s why, as a bourgeois crowd, they are so monstrously ugly. My God, how ugly they can be!

For Rottach-am-Tegernsee Robert’s theme was Pornography and Obscenity. Lawrence’s essay of that title appeared in Paris in the July-August-September 1929 issue of the literary magazine, This Quarter, before being published by Faber in expanded, booklet form that November. Here he tried to redefine obscenity as the presentation of sex as dirty, and referred to the previous century as ‘the eunuch century’.

In Bandol the theme was God and Religion. Robert gave an overview of Lawrence’s relationship to faith, and stressed how Lawrence turned back to the concept of God – a God of strength, beauty and life, rather than morality – in his last years. As Earl Brewster recalled in D. H. Lawrence: Reminiscences and Correspondence of 1934, ‘Lawrence’s conversations during his last months interested me more than ever; in one of the first he said to me: “I intend to find God: I wish to realize my relation with Him. I do not any longer object to the word God. My attitude regarding this has changed. I must establish a conscious relation with God.” These remarks surprised me, remembering how previously he had declared to my Brahmin friend that “God is an exhausted concept”’.

For Vence, Robert’s theme was Denial, Dying and Death. Robert said that Lawrence was in denial about his illness, and only a fortnight before his death, for the first time, alluded to his tuberculosis. In his last months several of his poems had death as their theme.

The presentation ended with a reading of a poem first published in Last Poems of 1933:

Gladness of Death

Oh death

about you I know nothing, nothing –

about the afterwards

as a matter of fact, we know nothing.

Yet of death, oh death

also I know so much about you

the knowledge is within me, without being a matter of fact.

And so I know

after the painful, painful experience of dying

there comes an after-gladness, a strange joy

in a great adventure

oh the great adventure of death, where Thomas Cook cannot guide us.

I have always wanted to be as the flowers are

so unhampered in their living and dying,

and in death I believe I shall be as the flowers are.

I shall blossom like a dark pansy, and be delighted

there among the dark sun-rays of death.

I can feel myself unfolding in the dark sunshine of death

to something flowery and fulfilled, and with a strange sweet perfume.

Men prevent one another from being men

but in the great spaces of death

the winds of the afterwards kiss us into blossom of manhood.

DISCUSSION

Catherine Brown asked Robert about how his understanding of Lawrence’s politics had changed over the course of his research for his book. He replied that he had initially thought that Lawrence’s hatred of Lloyd George dated back to his failure to create the ‘land fit for heroes’, which he promised when the war finished, but he had subsequently learned that it dated back to at least December 1916. Dudley Nichols added that it went back even earlier, but that it was sharpened in the autumn of 1916, when Lloyd George rejected the mooted settlement with Germany, and insisted on continuing to total victory. This led to two more years of war, and, arguably, the rise of Naziism and the Second World War. Catherine thought that this point was relevant to Europe’s current situation.

Montserrat Morera asked what Lawrence thought of Majorca. Robert replied that, in general, Lawrence disliked the Spanish; he initially enjoyed his time on Majorca, but then, as with so many other places, tired of it.

Jane Costin recommended Empty Bed Blues [hyperlink] as a piece of music, which was also about sexual abuse. She speculated that Lawrence’s reference to apples and sex in old age had reference to the fact that apples should be kept without touching, in order to stop each other going rotten – whereas Catherine thought that apples here connoted wholesomeness and non-edginess.

Jim noted that Lawrence flipped between love and hate, and thought that in order to do either one has to love or hate oneself. Robert noted that in Huxley’s introduction to Lawrence’s letters he posited that Lawrence hated people to the extent that he did precisely because he loved them so much: ‘”He sees”, Vernon Lee once said to me, “more than a human being ought to see. Perhaps,” she added, “that’s why he hates humanity so much.” Why also he loved it so much. And not only humanity: nature too, and even the supernatural. For wherever he looked, he saw more than a human being ought to see; saw more and therefore loved and hated more’ (p. xxxi). Catherine observed that Middleton Murry, in Son of Woman, thought likewise that Lawrence was frightened by the love that he felt, and, unlike his antetype and rival Jesus, took refuge in hate.

Philip wondered whether Lawrence had a late epiphany about the existence of God. Robert thought that his was more a case of a gradual turn to faith, such as occurs in many people as they near their deaths. Jim Phelps described the tension, of which he thought Lawrence to have been conscious, between the foreknowledge of death and the continual heartbeat of life. He thought that Lawrence was very brave.