Report of the Twenty-Ninth meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Robert Bullock

The Road to Vence 1928-1929

Thursday 25th May 2023

By Zoom

18.30-20.00 UK time

ATTENDERS

32 people attended, including, from outside of England, David Pratt in Regina Saskatchewan, Philip Chester in Deep River Ontario, Adam Parkes in Athens Georgia, Justin LaPoint in North Carolina, Shanee Stepakoff in Connecticut, Robert Bullock in Paris, Shirley Bricout in Vannes, Brittany, Nils Hedstrand in Munich, Kathleen Vella in Malta, Jim Phelps in Cape Town, and Philip Bfithis in the Philippines.

INTRODUCTION

Robert presented work-in-progress on his biographical account of the last two years of Lawrence’s life.

He summarises his book as follows:

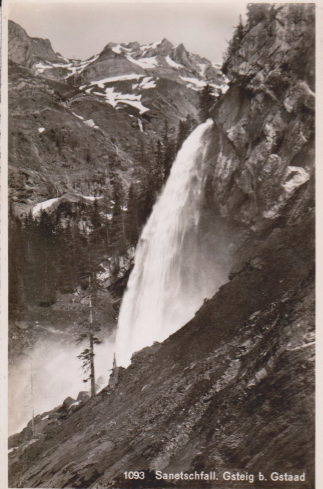

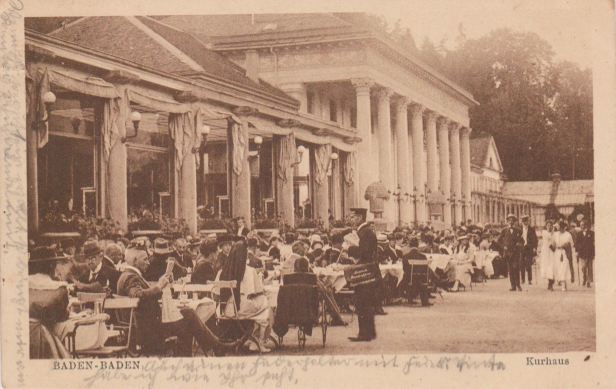

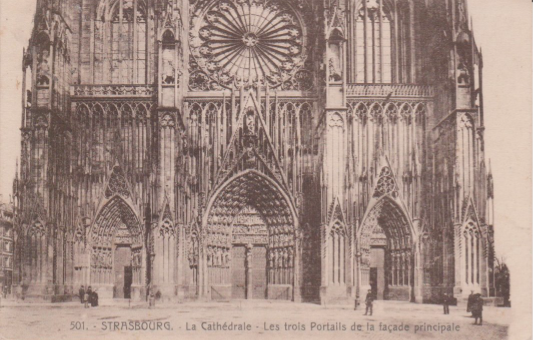

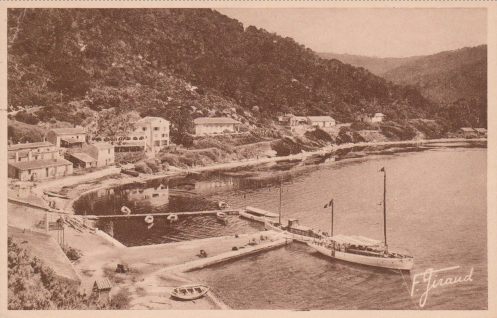

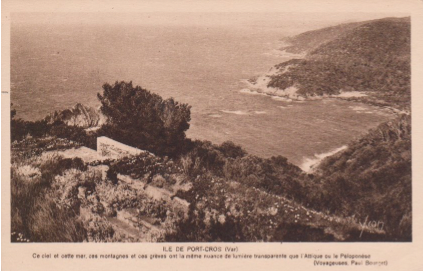

‘The starting point is his completion of Lady Chatterley and his stay with the Huxley party in Les Diablerets at the beginning of 1928, and it finishes with his admission to the Ad Astra sanatorium and death at the Villa Robermond in Vence in 1930. The main focus is on his character and what it was like to be with him through the eyes of those who spent time with him or came into contact with him during his final two years. Each chapter corresponds to a place in which he stayed during that period – in Switzerland, Germany, France, Italy and Spain. There will be fifteen chapters, plus an epilogue. I am including original 1920s/1930s postcard illustrations of all the different places he stayed at so that the reader gets a feel of the time and place and sees what Lawrence himself saw during his nomadic journeying through Europe in those last two years of his life.

In my presentation, I will focus not only on how those in Lawrence’s circle of friends, family and visitors saw him – Frieda, his sisters, Barby, the Brewsters, the Huxleys, Julian and Juliette Huxley, Rolf Gardiner, Brewster Ghiselin, Rhys Davies, Orioli, Maria Chambers and the Crosbys – but also to speak briefly about his own thoughts, feelings, opinions, prejudices, hatreds, etc., as he entered the final period of his life. For instance, the letters he wrote from Bandol during his first stay there reveal a lot about his latent racism, his attitude to the younger generation in England, his feelings about the French, his unfailing generosity and love of nature, his hatred of money and the rich, his thoughts on growing old, and his opinion about life and how it should be lived.’

The book’s structure is as follows:

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Florence – Les Diablerets

- Chapter 2 Villa Mirenda, Florence

- Chapter 3 Grenoble – Saint-Nizier

- Chapter 4 Saint-Nizier – Chexbres-sur-Vevey

- Chapter 5 Gstaad – Gsteig

- Chapter 6 Gsteig – Baden-Baden

- Chapter 7 Baden-Baden – Strasbourg – Le Lavandou

- Chapter 8 Le Lavandou – Port-Cros – Toulon

- Chapter 9 Toulon – Bandol

- Chapter 10 Paris

- Chapter 11 Carcassonne – Barcelona – Mallorca

- Chapter 12 Forte-dei-Marmi – Florence

- Chapter 13 Baden-Baden – Buhl – Baden-Baden – Rottach-am-Tergensee

- Chapter 14 Bandol

- Chapter 15 Vence

- Epilogue From Oblivion to Eternity

At the time of giving his presentation, Robert had finished eleven of the fifteen chapters; his presentation covered chapters one to nine (starting with the Lawrences’ holiday in Les Diablerets with Aldous and Julian Huxley and their families, soon after Lawrence had completed the final version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover).

Robert has promised to return to the London Lawrence Group to give another presentation on chapters ten to fifteen, once he has finished the book.

THE PRESENTATION

Chapter 1 Florence – Les Diablerets: 20th January-6th March 1928

Robert presented 1928 as a pivotal year in Lawrence’s life. He wrote to Kot that he felt in the abyss, but that something was bound to begin again anew. In fact, 1928 was the year in which he for the first time started to make a decent living (from journalistic articles, and then Lady Chatterley’s Lover). However, his health was deteriorating.

He and Frieda went to stay in Les Diablerets with the Huxleys’ extended family. Lawrence disagreed with the Huxley brothers about science (Lawrence hated the word, and said of its findings that ‘they may be facts, but they’re not truths’). He also found Julian supercilious towards his younger brother Aldous, and said so to Julian’s wife Juliette. She later described the situation in her 1986 memoir Leaves of the Tulip Tree:

‘I began to sense in Julian a restless impatience, an impervious need to assert himself … Our quiet days became charged with tension, Julian playing a part towards Aldous and me – a curious “I’m the king of the castle” role, excluding others in discussions. Aldous was courteous as always but also a little uncomfortable. It was not long before Lawrence began to resent Julian’s attitude. … he began to speak about what I always felt was my secret world. Profoundly embarrassed, I barely listened because my mother was there … Lawrence was hard on Julian: he thought him “an expurgated version of a man; like so many others, much the greatest danger for men” … I felt trapped, far too repressed to risk a discussion. What a chance I missed, sitting there frozen and numb … Dear Lawrence. He was full of the unpasteurised milk of human kindness, he blundered into vulnerable situations, knowing that he was right and that all would be well if only people listened to him. He believed in taking action whatever the moment or results’

For his part, on 17th April 1928 Lawrence wrote in a letter to Juliette: ‘I was so relieved when you said it was better with you and Julian now, and that something had come free. I’m so glad. After talking to you … that evening in such a burst, I said to Frieda: I wish to God I’d kept my tongue still.’

Chapter 2 Villa Mirenda, Florence: 6th March-10th June 1928

Villa Mirenda, Florence

Back in Florence Lawrence resumed his relationship with Pino Orioli, whom he had known in Cornwall during the First World War. He brought him the typescript of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which had been typed in part by Catherine Carswell and in part by Maria Huxley after his old friend Nellie Morrison refused to continue after the first five chapters. Orioli not only published the novel but helped him in other ways, including by bringing provisions to the Villa Mirenda. Lawrence drove a hard bargain with him on the novel, however, and Orioli had mixed feelings about him, perhaps also being influenced by the attitudes of his partner Norman Douglas.

In his 1937 Adventures of a Bookseller, Pino recalled:

‘I was not officially the publisher, though I had all the publishing work to do, and a most trying job it was … Much as I like some of his work, I never had any deep feeling for him as a man. One always had to be on one’s guard with Lawrence – his querulousness and chronic distrust of everybody made a real intimacy impossible. Sometimes his behaviour led me to wonder whether he was not suffering from persecution mania.

… Lawrence was more troublesome than anyone I have ever dealt with, and as a friend so incalculable and often so disappointing, so disheartening, that now and then I wonder how many of those who knew him well were really sorry when he died.

… Lawrence was a homosexual gone wrong; repressed in childhood by a puritan environment. That is the key to his life and writings.’

However, in 1954 Richard Aldington in Pinorman wrote that Orioli had spoken about Lawrence with great respect soon after he died:

‘I can testify that around 1930-32 Pino spoke of Lawrence with the greatest respect for his memory. He even talked of trying to get permission … to put a small memorial tablet on the pine tree near Scandicci under which Lawrence wrote most of “Lady C”’.

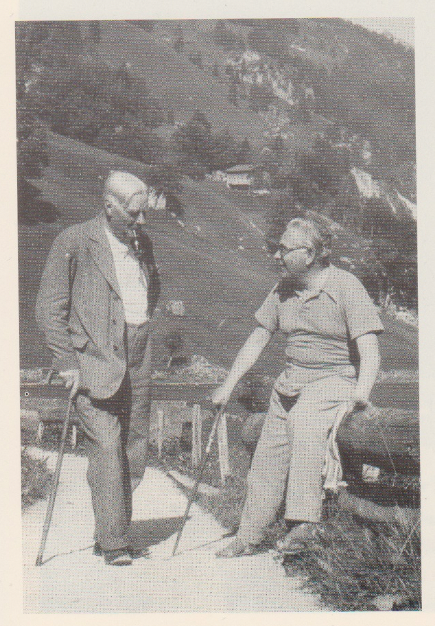

Norman Douglas and Pino Orioli in the early 1930s

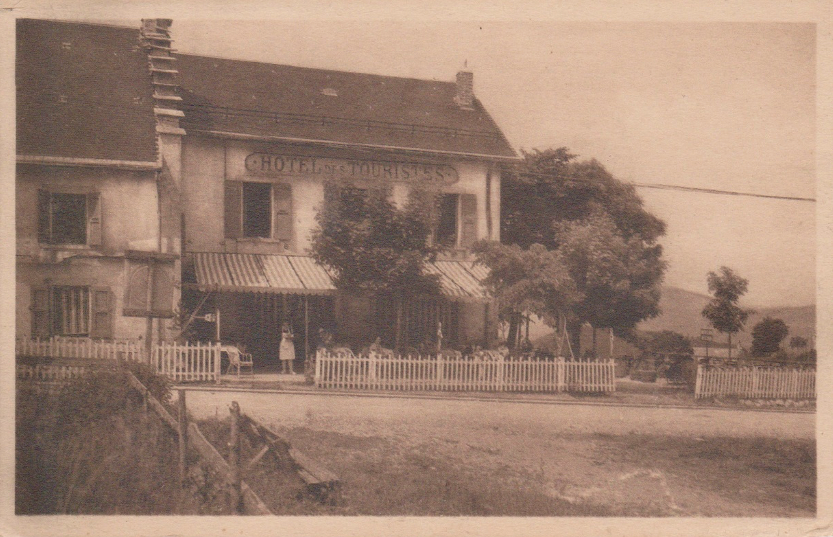

Chapter 3 Florence – Grenoble – Saint-Nizier: 10th -15th June 1928

The Lawrences then went with the Brewsters to Saint-Nizier, a remote mountain village west of Grenoble. Here an unpleasant incident took place: Lawrence coughed through the night in their hotel room, and the following morning they were requested to leave, because of a local bylaw to the effect that people with TB were not allowed to stay at the hotel.

The Brewsters, in their 1934 D. H. Lawrence – Reminiscences and Correspondence, recalled:

‘Early in the morning, after our first night there, the proprietor knocked at Earl’s door … he was sorry not to be able to keep Lawrence, but there was no choice since the law on that plateau prohibited his having guests with affected lungs. Monsieur would have to go.

Ill as Lawrence was, he had never admitted to us the seriousness of his malady. He had continued to refer to it as an “annoying” irritation of his bronchials. Never before had the doors of a hotel been closed to him because of it. Shocked and dismayed, we had to break this news to Frieda, whom it upset still more. It was decided not to tell Lawrence what had happened.’ For his part, Lawrence recalled to Orioli on 21st June 1928:

‘That St. Nizier place was very rough – and the insolent French people actually asked us to go away because I coughed. They said they didn’t have anybody who coughed. I felt very mad.’

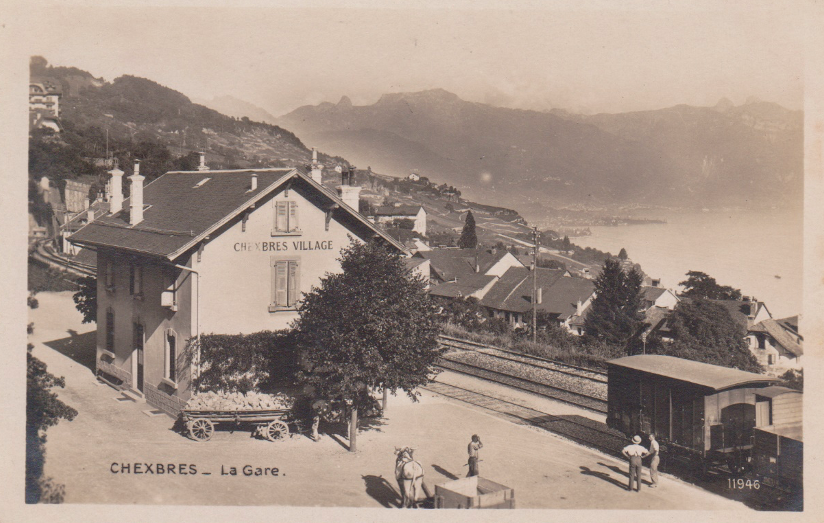

Chapter 4 – Saint-Nizier – Chexbres-sur-Vevey: 15th June – 6th July 1928

During the period when Lawrence went to Chexbres-sur-Vevey on Lake Geneva, Frieda went to visit her mother, but was also seeing her lover Ravagli. Juliette Huxley (in Leaves of the Tulip Tree) said that ‘When (Frieda) vanished on one of her periodic prowls, (Lawrence) was left vulnerable like an orphan.’ Robert described Lawrence as ‘sad if understanding’. For her part, Frieda wrote to her mother in April-May 1928:

‘But you know very well, just as I want to travel, L. gets ill … I’m well otherwise, but with every bit of inward strength I make myself slowly freer; I can’t bear always just living this illness – and always just sacrificing myself – that’s not what I understand by life.’

Frieda’s daughter Barbara Weekly Barr, in her 1954 Memoir, recalled:

‘Aunt Else told me that whenever she heard her sing (‘The Lay of the Imprisoned Huntsman’) she felt sad, because there was a sound in Frieda’s voice of a being also imprisoned.

In their life together, Frieda must sometimes have suffered, and felt lonely … Lawrence was inclined to be jealous … The strain on her remarkable good humour must have been colossal. She believed in him, though. He needed her belief and was most unhappy without her.

At this time (April 1928) she wanted a holiday by herself. I was going back to Alassio. She came too, and then went off alone. Lawrence said to Maria Huxley, “Frieda has changed since she went away with Barby.” He did not reproach my mother. One evening at the Mirenda he said to her, “Every heart has a right to its own secrets.”’

The Brewsters recalled:

‘On the day for Frieda’s return from Baden-Baden Lawrence consulted the timetable and decided she would arrive by ten in the morning. As no Frieda appeared he met the twelve o’clock express, with the same result. He ate his lunch hurriedly and rushed back for the two-twenty local, but returned shortly looking disconsolate … We tried to cheer him up, but in vain. He always looked forward so eagerly to her return.’

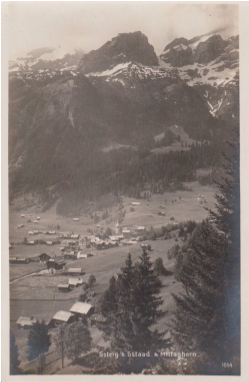

Chapter 5 Gstaad – Gsteig: 6 July-18th Sept 1928

Lawrence chose a very high chalet above Gsteig for the sake of his lungs, and on 11th July 1928 invited his elder sister Emily and his niece to come and visit him there:

‘It’s a very pretty place – I wish you could see it. Would you venture to come for a fortnight if I sent you the money? We have a room upstairs you could have.’

They came, but unfortunately for three of the twelve days of their visit, it rained continuously. Lawrence felt estranged from his relatives: ‘I have to hide “Lady C.” like a skeleton in my cupboard’ (letter to Orioli of 30th August 1928); ‘I am not really “our Bert”, Come to that, I never was. And the gulf between their outlook and mine is always yawning, horribly obvious to me.’ (letter to Enid Hilton, 31st August 1928).

It was therefore a sad visit, during which he ‘made [a] design for my tombstone in Gsteig churchyard, with suitable inscription: “Departed this life, etc. etc. – He was fed up!”’ (letter to the Huxleys 31st July 1928). It seems that the altitude did not restore him, and his cough still tormented him. He admitted to being incapable of walking even short distances – which meant that visits to Gsteig were rarely possible because of the mile-long climb back uphill afterwards.

Chapter 6 Gsteig – Baden-Baden: September 18th – October 1st 1928

During this visit to Frieda’s mother in Baden-Baden, Lawrence was kind and attentive. In a letter to Ada the year before (October 9th 1927), he had described his mother-in-law as ‘wonderful – seems to get younger. She was out with us to tea at the Kurhaus … very pretty and elegant. She is really very nice – and whatever she can do for me, she does it – thinks of everything possible.’ Frieda recalled in Not I, But the Wind in 1935: ‘Lawrence and my mother were fond of one another … Especially after the war, she and (he) became great friends … She was very happy in his life and mine, it meant so much to her … Lawrence and my mother in her wisdom and ripeness understood each other so well. She said to me: “It’s strange that an old woman can still be as fond of a man as I am of that Lorenzo”.’

But when he stayed with her again in August 1929 at a hotel in the hills above Baden-Baden – which he wanted to leave because of the bad weather but where she insisted on staying – he was less kind. On 2nd August 1929 he wrote to Ada: ‘Frieda’s mother really rather awful now. She’s 78 and … thinking her time to die may be coming on. So she fights in the ugliest fashion, greedy and horrible, to get everything that will keep her alive … nothing exists but just for the uprpose of giving her a horrible strength to hang on a few more years … that old woman would see me die by inches and yards rather than relinquish her “mountain air” … It’s the most ghastly state of almost insane selfishness I ever saw – and all comes of her hideous terror of having to die … May god preserve me from ever sinking so low. I never felt so cruelly humiliated.’

Chapter 7: Baden-Baden – Strasbourg – Le Lavandou: October 1st – 14th 1928

On arrival in Strasbourg the Lawrences and the Brewsters went to see the cathedral. As the Brewsters recall in their 1934 D. H. Lawrence: Reminiscences and Correspondence: ‘Though it was cold … when we arrived at Strasbourg, we set forth to explore the cathedral. Lawrence thought it had the beauty of both the French and German Gothic; he liked its exterior best of all Gothic cathedrals.’

Afterwards, in order stay warm, they went to see Ben Hur at the cinema; the Brewsters recall: ‘There was no human touch, nothing resembling a reality of any case of life we knew or could imagine. Lawrence gasped out that he was going; if we did not take him out immediately, he would be violently sick; such falsity nauseated him; he could not bear to see other people there open-mouthed, swallowing it, believing it to be true.’

Robert added that Lawrence would doubtless have been horrified to know that 150 horses had been reported killed during the making of the film’s chariot race.

During their time with the Brewsters in the summer of 1928, Lawrence criticised Earl Brewster’s painting and writing, which Brewster took very well; theirs was an easy relationship during the last few years of Lawrence’s life.

Chapter 8 Le Lavandou – Port-Cros – Toulon: October 15th-November 17th 1928

This visit was undertaken with Richard Aldington, his current lover Arabella Yorke, and his former lover Brigit Patmore – and was not a happy time for any of them. A tension arose between Lawrence and Aldington over the latter tending back towards Brigit, which fact greatly upset Arabella (who threatened and tried to commit suicide). Aldington, in his 1941 memoir Life for Life’s Sake, described Lawrence’s talk as ‘too personal and satirical, sharp with the reckless hatred of those about to die’. And in his 1951 Portrait of a Genius, But… he wrote ‘Poor Lawrence! … It was a bitter heart-break … to find that he had to spend his sdays in bed or in a deck-chair … how frail and ill he was, how bitterly he suffered, what frightening envy and hatred of ordinary healthy humanity sometimes possessed him, how his old wit had become bitter malice, how lonely he was, how utterly he depended on Frieda, how insanely jealous of her he had become.’ Regarding this last point Brigit Patmore, in her 1968 My Friends When Young, wrote that Frieda ‘had always to bear the worst. We occasionally received a cool flick, but she got it straight from the electric current.’ Aldington wrote to Hilda Doolittle at the time: ‘Up in that lonely Vigie, a mile from the nearest house, it was like a series of demented scenes from Wuthering Heights’.

Lawrence’s Pansy ‘The Noble Englishman’ may well have been based on Aldington (as may ‘How Beastly the Bourgeois Is’):

I know a noble englishman

who is sure he’s a gentleman,

that sort –

This moderately young gentleman

is very normal, as becomes an englishman,

rather proud of being a bit of a Don Juan

you know –

But one of his beloveds, looking a little peaked

towards the end of her particular affair with him

said: Ronald, you know, is like most englishmen,

by instinct he’s a sodomist

but he’s frightened to know it

so he takes it out on women.

Oh come! said I. That Don Juan of a Ronald! –

Exactly! she said. Don Juan was another of them, in love with himself

and taking it out on women. –

Even that isn’t sodomitical, said I.

But if a man is in love with himself, isn’t that the meanest form of homosexuality? she said.

You’ve no idea, when men are in love with themselves, how they wreak

all their spite on women

pretending to love them.

Ronald, she resumed, doesn’t like women, just acutely dislikes them.

He might possibly like men, if he weren’t too frightened and egoistic.

So he very cleverly tortures women, with his sort of love.

He’s instinctively frightfully clever.

He can be so gentle, so gentle

so delicate in his love-making.

Even now, the thought of it bewilders me: such gentleness!

Yet I know he does it deliberately, as cautiously and deliberately as when he shaves himself.

Then more than that, he makes a woman feel he is serving her

really living in her service, and serving her

as no man ever served before.

And then, suddenly, when she’s feeling all lovely about it

suddenly the ground goes from under her feet, and she clutches in mid-air,

but horrible, as if your heart would wrench out; –

while he stands aside watching with a superior little grin

like some malicious indecent little boy.

– No, don’t talk to me about the love of englishmen!

Eventually the party was driven off the island by storms physical and mental.

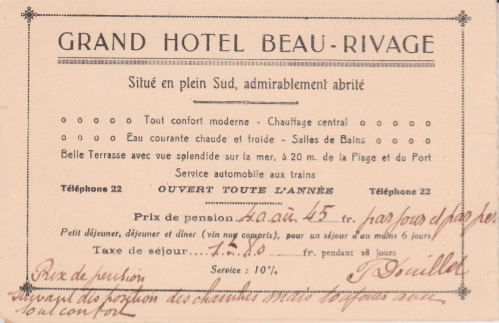

Chapter 9 Toulon – Bandol: 17th November 1928 – 11th March 1929

At Bandol the Lawrences were visited by Rhys Davies, who recorded ugly rows between Lawrence and Frieda, including over Rasputin, to whose description in a book about Rasputin Frieda expressed attraction. In his 1940 article D. H. Lawrence in Bandol Davies noted that at the Grand Hotel Beau-Rivage ‘was a young negro waiter. Lawrence took … a deep dislike to the youth. The dislike was so intense and its object so innocently unaware of it that I was vastly amused. To see Lawrence’s eyes gleam with watchful revulsion … seemed utterly grotesque to me: why be so stirred over the young man?’ Lawrence also disapproved of the waiter’s engagement to a young white governess staying at the hotel.

Overall, however, it was a good stay. Lawrence wrote to Maria Huxley on 21st November 1929:

‘It is incredibly lovely weather, the place very lovely, swimming with milky gold light at sunset, and white boats half melted on the white twilight sea, and palm trees frizzing their tops in the rosy west, and their thick dark columns down in the dark where we are, with shadowy boys running and calling, and tiny orange lamps under the foliage, in the under dusk. Then we come in and have tea in my room looking south where the moon is, and get sticky with the jammy cake.’

THE DISCUSSION

Robert acknowledged that he has mixed feelings about Lawrence during his last couple of years, but that Lawrence’s suffering under his illness excused a lot, and that he remained brave and extremely productive. Jane Costin observed that Lawrence’s rages were nothing new, and had been witnessed by both Jessie Chambers and Louie Burrows. She also asked how Lawrence had come to meet with Orioli in Cornwall during the War; David Ellis thought that since Orioli kept a bookshop in London with a friend, Lawrence may have got to know him there. Jim Phelps felt that Lawrence’s art was more important than his biography, but Robert responded that his book pays considerable attention to his works. After the event, Philip Chester wrote to me [Catherine Brown] as follows:

‘I was wondering how Robert would account for the bitter, vitriolic, mean spirited acrimony that existed between two supposed life-long “friends” in Lawrence and Aldington because, to me, it seems way, way over the top. Yes, Lawrence was a very sick man “dying in his clothes” and Aldington “shell shocked”, – both very serious physical, emotional, spiritual and psychological conditions – but… I believe that that Port Cros episode among intimate friends – Frieda, Lawrence, Aldington, Arabella and Brigit Patmore – has the makings of a Chekhovian or Ibsen-like play (or Hollywood screenplay). I wonder if anyone has undertaken such a project…? … In my view, that month on that French island in 1928 was a critical turning point in all their lives just as Lawrence’s visit to Padworth in 1926 had been, both occasions of literary significance, of course, but my sympathy lies with Arabella, and I believe her story needs to be told.’