The following is the pre-edited version of an article which has been published in Etudes Lawrenciennes (52: 2021), and which was developed from a paper that I gave at the International D.H. Lawrence Conference at the University of Nanterre, Paris, 29-31 March 2018. The topic of this conference, which is also that of this edition of the journal, was Resisting Tragedy.

Keywords

Darwin, tragedy, comedy, evolution, degeneration

Abstract

Darwin’s theories helped both to destroy D.H. Lawrence’s early Christianity, and to shape the latter’s beliefs in the primacy of the organic, of non-rational forces, and of the animalityof man – even though Lawrence soon saw materialism as begging more questions that it answered. He therefore reinterpreted Darwinism in social terms, and contextualised it on the one hand by the individual’s imperative to flourish on his/her own terms, and on the other by a divine, eternally-creative principle. Individuals’ failure to achieve flourishing in the face of Darwinian-social imperatives are seen by him as tragic in proportion to the magnitude of their attempt, yet always on a limited scale, and wholly contextualised by the comedic, eternal life-generating principle. The same applies to the degenerationof civilizations and even of species, which will always replaced by more vital forms. Lawrence is therefore firmly amongst those writers whose understanding of Darwinian evolution fits into a comedic rather than a tragic world-view, in contrast to his great novelistic predecessor Thomas Hardy. Yet, in the case of the social Darwinist character, Gerald Crich in Women in Love, the comedic vision struggles to contain the novel’s tragic treatment of his death.

Introduction: Darwin’s Impact on Tragedy as World-View

Charles Darwin’s, and D.H. Lawrence’s, relationships to the concept of tragedy have been severally much studied.[1] Darwin’s impact on Lawrence has been somewhat less considered, whilst the impact of Darwin on Lawrence’s relationship to tragedy has hardly been considered at all.[2] If the significance of Gerald Crich’s death in the Alps is a mountain, which critics have tried to scale by very various routes, then the assault that this article will make on it is up the path of evolutionary theory, with the pickaxes, as it were, of the concepts of tragedy and comedy. By focusing on Lawrence’s response to Darwin, a new understanding of Lawrence’s sense of the tragic will emerge. Moreover, Lawrence’s positive apprehension of life, and an optimistic envisioning of its future survival and thriving (in short his Bejahung – saying yes) will be contrastively adumbrated as a comedic vision, which for Lawrence was inseparable from his understanding of evolution.

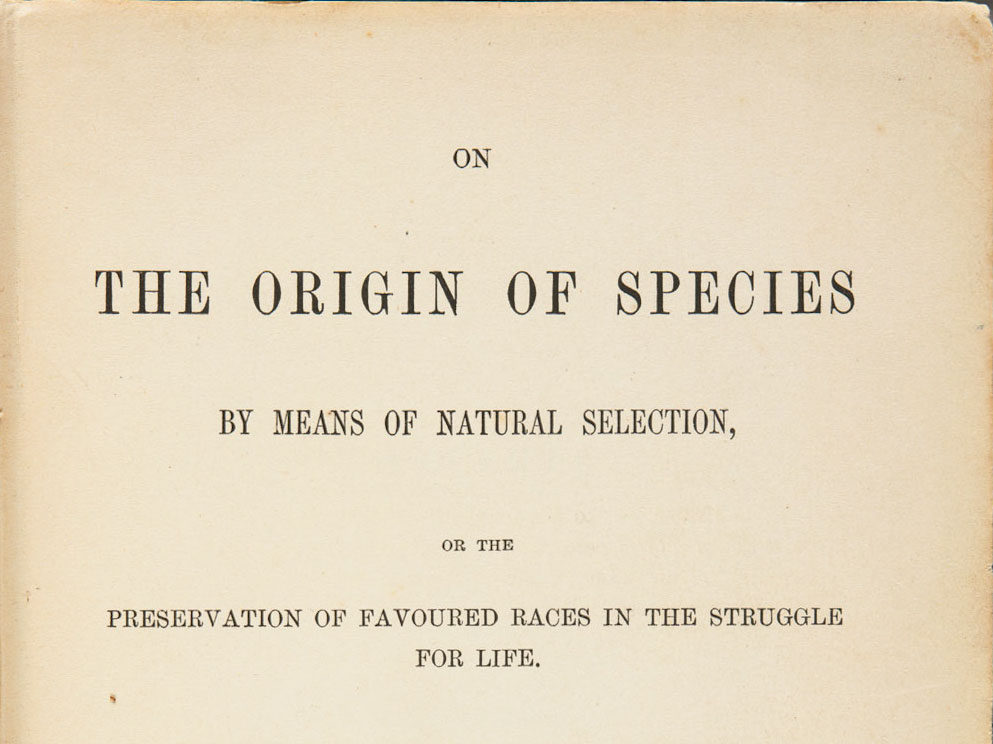

Gerald Crich has frequently been described as tragic, and with good reason.[3] The novel presents him as a proud, sensitive and potentially great man, from a cursed dynasty, who chooses wrongly. His former lover Gudrun’s judgment of his as a “barren tragedy” is connected to her sense of it as “A pretty little sample of the eternal triangle!”, one proximate reason for his passive suicide in the snow having been her involvement with another man (WL 476, 477). This judgment rhymes with Lawrence’s concept of sex tragedy as described with derision in his writings from 1918 onwards. In the first version of Studies in Classic American Literature (1918-19), he refers to a type of struggle in which “the sexes act in the polarity of antagonism or mystic opposition, the so-called sensual polarity, bringing tragedy” (SCAL 268). In Fantasia of the Unconscious (1921), Lawrence commends the fact that “Tolstoi said No to the passion and death conclusion” in Anna Karenina, even though he rejected Levin’s alternative of a Christian epiphany (PUFU 200). The narrator of Mr Noon (1920-21) emphasizes the banality of such an end: “‘Man survives earthquakes, epidemics, the horrors of disease, and all the agonies of the soul, but as long as time lasts his most excruciating tragedy is, has been, and will be – the tragedy of the bedroom’ […] I am quoting the great Leo Tolstoi, who, in such matters […] seems to me a quite comical fool” (MN 190).[4] Yet this is not the only way in which Gudrun’s description of Gerald’s death as a “barren tragedy” can be interpreted. Paying rather more literal attention to the adjective than this reading permits, takes us, I suggest, back to 1859 and the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection.

This book was variously received as comedic and tragic, just as it was also claimed in support of socialist and capitalist political extremes.[5] Gillian Beer attributes this range of interpretability to the book’s “subjective and literary” qualities, which she in turn attributes in part to its own status as an imaginative explanation for phenomena, which cannot be empirically verified: “The experience [of reading The Origin of Species] may seem to diverse readers to be tragic […] or comic […] but it is always subjective and literary.”[6] Moreover, the book itself “sways between an optimistic and a pessimistic interpretation: it gives room to both comic and tragic vision […] ‘Descent’ may imply [man’s] fall from his Adamic myth or his generic descent (ascent) from his primate forebears”.[7]

On the one hand, Darwin offered a comedic vision of natural abundance and diversity, “a new creation myth which challenges the idea of the fall”, and a perception of humanity as the apex of creation, on the understanding that its future progress was to be mental and that its “physical evolution was complete”.[8] The German populariser of Darwin, Ernst Haeckel, who made at least as great an impression on Lawrence as did Darwin himself, took Darwin’s ideas “as a kind of theological doctrine, recasting it as the foundation for his ‘religion of monism’”.[9] The Deutscher Monistenbund was founded in 1906, and had an optimistic, metaphysical vision of monism operating in a cosmic evolutionary process, in which atoms possessed souls.[10] As Robert Richards argues, this provided an optimistic substitute for the Christianity in which Haeckel had lost belief.[11]

The bleakest social Darwinist assessment of European civilization was that of Max Nordau’s 1892 Entartung (Degeneration): “We stand now in the midst of a severe mental epidemic; of a sort of black death of degeneration and hysteria, and it is natural that we should ask anxiously on all sides: ‘What is to come next?’” Yet, having drawn from Darwin’s 1871 The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex the principle that (in Nordau’s words) “Degenerates, hysterics, and neurasthenics are not capable of adaptation. Therefore they are fated to disappear”, his answer to his question was ultimately comedic: “Humanity has not yet reached the term of its evolution […] It is still young, and a moment of over-exertion is not fatal for youth; it can recover itself”.[12]

Certain writers, such as Samuel Butler and George Bernard Shaw, were provoked by Darwin to return to a Lamarckian vision of evolution (i.e. one in which individuals can enhance their survivability through their own efforts rather than simply benefitting from random genetic mutation, and can then pass on, for example, their enhanced musculature to their offspring).[13] It was the lack of agency on the part of either God or man that had distressed many about Darwin, and made him one of the three blows to the human ego that Freud posited as having been delivered by himself, Copernicus and Darwin.[14] This, along with the theses of constant competitive struggle, the eventual extinction of species (which Lamarck, although not the geologist Lyell, had denied), and the eventual heat death of the earth, led others to take Darwin tragically. Insofar as they were unconvinced by Darwin’s suggestion that evolution had been set in motion by a divine agent which had then stood back,[15] and insofar as Christian authorities rejected any of Darwin’s propositions, a conflict arose between Darwinism and that Christianity which was itself comedic, in that it presented a vision of eternal happiness for the just.

These conflicts are apparent in Tennyson’s In Memoriam A.H.H., a poem that strongly anticipated the Origin and was suffused by its predecessors, which veers between a comic and tragic response to what was at that time known as the development hypothesis. The former response sees Hallam as a “noble type” of a future, perfected mankind, and perceives that “all we thought and loved and did,/ And hoped, and suffer’d, is but seed/ Of what in them [future mankind] is flower and fruit”; the latter asks “Are God and Nature then at strife/ That Nature lends such evil dreams?/ So careful of the type she seems, / So careless of the single life.”[16] It was the tragic rather than comedic implications of Darwin that were predominantly absorbed by Lawrence’s immediate predecessors, including Matthew Arnold, Thomas Hardy, H.G. Wells, Émile Zola, Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg.

One notable aspect of these writers’ responses is that they imply an attitude towards life per se– that it is tragic (not “a tragedy”, since that noun implies temporal delimitation, but “tragic”, which adjective can attach itself not only to a character, but to an atemporal, spatial concept such as the universe). This shift was partly if not exclusively correlated to the recent entry of tragedy to the more realistic form of the novel.[17] Previous to the nineteenth century, I suggest, tragedies – whether written by part-time tragedians such as Shakespeare (in the sense that they also wrote comedies), or full-time tragedians such as Aeschylus or Racine – did notimply that life was tragic, their tragedies being reflective upon and responsive only to certain aspects of it. A tragedy’s universe being tragic did not of itself imply a tragic universe, as the society to tragedy of satyr plays on the ancient Greek stage, and of jigs on the Globe stage, stressed.

Nor was it the case that this shift towards a tragic vision of life, which took place progressively over the nineteenth century, pertained exclusively to its own time as “essentially a tragic age”, as the opening of Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928) puts it.[18] It was a trans-temporal conception, influenced by factors including the Romantic valorisation of the sublime, philosophers including Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, developments in psychology, the decline of religious faith, and scientists such as Lyell and Darwin. It was manifested in a recovery of a seriousness that had for centuries been lost in the dramatic tragedies and opera, as Nietzsche had diagnosed in his 1872 Die Gebürt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik (The Birth of Tragedy out of the Spirit of Music).

Robert Dupree notes that the forty years following the publication of this work were an intensive period for playwrights wanting to recover the spirit of ancient Greek tragedy: “Succeeding writers were eager to take up the challenge launched in 1872 by a young academic”. He also notes that “the radical drama of the later 1800s was at least a protest, in the name of a serious return to the tragic dimensions of human experience, against a shallow theater given over almost entirely to spectacle, intellectually empty entertainment, and audience gratification.”This also correlated to a shift from a South to a North European sensibility, as Dupree argues is reflected in Arnold’s “Dover Beach” in its shift from ‘the Aegean’ (by which ‘The eternal note of sadness’ was once heard by Sophocles) to “this distant northern sea” (where it is now heard by Arnold).[19]

This challenge to the distinction between art and life also correlated to a more expansive role for artin the later nineteenth century, as polemically asserted by the aesthetes, as invited by the more circumscribed role of religion, and as characterised by Nietzsche in his “Attempt at a Self-Criticism” of The Birth of Tragedy as “an ARTISTIC view of life”. Although Nordau diagnosed such a view as itself degenerate, he too analysed the degeneracy of contemporary Western civilisation according to its arts.

D.H. Lawrence and Darwin

Lawrence, then, was born into a period of the resurgence of tragedy as an art form and in application to life, which was in part a response to Darwin. He had first read Darwin when he was around seventeen. Jessie Chambers remembers that “He came upon [rationalist writers] at a time of spiritual fog, when the lights of orthodox religion and morality were proving wholly inadequate”.[20] In turn, his reading of Darwin and other materialists helped to break down his Christianity, which was in any case troubled by the problem of suffering. He wrote to his Unitarian Minister Robert Reid: “Men – some – seem to be born and ruthlessly destroyed; the bacteria are created and nurtured on Man, to his horrible suffering […] I do not wage any war against Christianity – I do not hate it – but these questions will not be answered” (L i. 47). He was not convinced by the series of lectures which Reid gave in response to his questions.[21]

Yet by the following year, 1908, he had already gained a distance from Darwin. In his first public talk, to the Eastwood Art Society, “Art and the Individual”, he adduced the Darwinian interpretation of the white swan’s plumage – that it was expressive “of the great purpose which leads the swan to raise itself as far as possible to attract a mate, the mate choosing the finest male that the species may be reproduced in its most advantageous form”, but then belittled this interpretation as mere “knowledge”, in contrast to more profound aesthetic appreciation (STH 226). Thereafter he mentioned Darwin relatively little, and not at all in his fictionalisation of this period of his life in Sons and Lovers.

He mentioned Ernst Haeckel rather more. He had learned about him from his admired botany teacher at University College Nottingham, Ernest Alfred Smith, who also “showed him the way out of [Haeckel’s] torturing crude Monism […] into a sort of crude but appeasing Pluralism” (L i. 147). Lawrence marked this distance by his satirical depiction of The Rainbow’s mischieviously named Dr Frankstone, who is a materialist monist, and a positivist who believes that physical reality alone can be investigated. As Ebbatson points out, “As Ursula perceives at college, the offered culture is a mirror-image of the industrial base.”[22] When Ursula looks at a unicellular creature through a microscope, she reflects: “If it was a conjunction of forces, physical and chemical, what held these forces unified, and for what purpose were they unified? […] What was the will which nodalised them and created the one thing she saw? What was its intention? To be itself? […] But what self?” (R 408) This attitude, which is supported by the novel’s rhetoric, recalls that of George Eliot’s response to The Origin of Species when it first came out: “To me the Development Theory and all other explanations of processes by which things come to be, produce a feeble impression compared with the mystery that lies under the process.”[23]

Six years after Women in Love, Lawrence was making a similar critique of evolutionary materialist explanations, in “Him With His Tail in His Mouth”:

‘Evolution sings away at the same old song. Out of the amoeba, or some such old-fashioned entity, the dragon of evolved life stretches himself enormous and more enormous only, at last, to return each time, and put his tail into his own mouth, and be an amoeba once more. […] How do you know? How does anybody know, what always was or wasn’t? Bunk of geology, and strata, and all that, biology or evolution. […] Why does man always want to know so damned much? Or rather, so damned little. If he can’t draw a ring round creation, and fasten the serpent’s tail into its mouth with the padlock of one final clinching idea, then creation can go to hell, as far as man is concerned. […] What we want is life, and life-energy inside us. Where it comes from, or what it is, we don’t know, and never shall. It is the capital X of all our knowledge.’ (RDP 309-10)

Nonetheless, Lawrence took inspiration and support for numerous aspects of his thought from Darwin: his sense of nature as organic rather than mechanical;[24] his acceptance of the kinship of humans, animals and all living beings; his valorisation of flux.[25] As Margot Norris comments, Lawrence’s practice is “to insert aspects of Darwinian living form, such as temporality, mutability, and susceptibility to chance, into literary conventions, thereby transforming character into multiplicitous and fluid ‘allotropes’, eschewing novelistic closure”.[26] For all Lawrence’s critique of Darwin’s rationalist mode, his anti-rationalism rhymed well with the non-rationalist contents of that thought: as Norris puts it: “trivial organic forces operating unconsciously and irrationally, on an ad hoc basis, subject to chance, over time”, with “its perilous and ironic consequence, that reason is enthralled to the organic”.[27]

Lawrence therefore blended elements of Darwin’s thought with that of others and his own in a synthesis which rejects the mode and some of the contents of that thought, but in which numerous of its implications are nonetheless apparent. Moreover, as the range of texts from Study of Thomas Hardy (1914) to Apocalypse (1930), to which I will refer, will make apparent, his vision of evolution remained in its broad outline unevolved throughout his writing career. The question is then whether Lawrence’s idiosyncratic appropriation of Darwin is comedic or tragic, if either.

D.H. Lawrence and Darwinian Comedy

I would suggest overwhelmingly the former. As discussed, Lawrence was born into a period of the resurgence of tragedy as a genre and its emergence as a world-view. With his own degenerative illness, he constant money problems, and his horror at the War, he had perhaps many inducements towards such a world-view, yet his career can be interpreted as a passionate struggle towards the attainment and articulation of a comedic world-view. With regard to evolution, The Study of Thomas Hardy gives a positive sense of ever greater differentiation:

‘Life starts crude and unspecified, a great Mass. And it proceeds to evolve out of that mass ever more distinct and definite particular forms, an ever-multiplying number of separate species and orders […] So on and on till we get to naked jelly […] to me: and on and on, till, in the future, wonderful, distinct individuals, like angels, move about, each one being himself […]’ (STH 43)

As Ebbatson argues, the emphasis on “the transformation of the homogenous into the heterogeneous […] an advance presupposed in the Spencerean definition of evolution as change from incoherence into coherence” was also that of Herbert Spencer’s 1862 First Principles, which had strongly influenced Lawrence.[28] This optimism has echoes in Lamarck and also in Russel Wallace, who also thought that human progress “affords us the surest proof that there are other and higher existences than ourselves, from whom these qualities may have been derived, and towards whom we may ever be tending.”[29] It is echoed too by the ending of The Origin of Species: “from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved”.[30]

There is considerable affinity between this optimism and that of Rupert Birkin, when he contemplates in the presence of his best friend’s (Gerald Crich’s) corpse that:

‘If humanity ran into a cul de sac and expended itself, the timeless creative mystery would bring forth some other being, finer, more wonderful, some new, more lovely race, to carry on the embodiment of creation. […] Races came and went, species passed away, but ever new species arose, more lovely, or equally lovely, always surpassing wonder.’ (WL 479)

Lawrence’s vision of God is as more active, and therefore more comedic, than Darwin’s concept of God as setting evolution in motion then standing back, as the latter suggests on the penultimate page of The Origin of Species:

‘Authors of the highest eminence seem to be fully satisfied with the view that each species has been independently created. To my mind it accords better with what we know of the laws impressed on matter by the Creator, that the production and extinction of the past and present inhabitants of the world should have been due to secondary causes, like those determining the birth and death of the individual. When I view all beings not as special creations, but as the lineal descendants of some few beings which lived long before the first bed of the Silurian system was deposited, they seem to me to become ennobled.'[31]

The account of creation suggested by this passage was accepted by some “reconciliationist” Christian Darwinists, echoing as it did Saint Augustine’s argument that God planted the seeds of potentiality to develop over time.[32]

Yet Lawrence revised Darwin still further when it comes to purposiveness. God’s function may be to generate ever new, at least as good beings. But the purpose of those beings is not merely to survive and reproduce themselves, but to fulfill themselves as individuals – as is set out at length in Study of Thomas Hardy, and as underpins much of Lawrence’s thought thereafter. Early in the book, Lawrence asserts that “The world is a world because of the poppy’s red. Otherwise it would be a lump of clay” (STH 13). His point, contra Darwin, is that the primary purpose of the poppy’s redness is not to further its self-reproduction, but to further the individual poppy’s self-fulfillment in splendid flowering:

‘Yet we must always hold that life is the great struggle for self-preservation, that this struggle for the means of life is the essence and whole of life. As if it would be anything so futile, so ingestive. Yet we ding-dong at it, always hammering out the same phrase, about the struggle for existence, the right to work, the right to the vote, the right to this and the right to that, all in the struggle for existence, as if any external power could give us the right to ourselves.’ (STH 13)

It follows that shortness of life, physical decline and the absence of reproduction were not, to Lawrence, degenerative signs – as he had perhaps some personal motive to feel, Granofsky reminds us.[33] Lawrence writes:

‘That she bear children is not a woman’s significance. But that she bear herself, that is her supreme and risky fate: that she drive on to the edge of the unknown, and beyond. […] Man is man, and woman is woman, whether no children be born any more for ever.’ (STH 52-53)

Granofsky also argues that Lawrence was concerned that his ideas would die out – but Lawrence’s own stress on the flux and transience of his ideas and feelings functions to undermine such concerns, celebrating them as part of the temporary flowering of his own being. As he wrote in the 1929 ‘Foreword’ to Pansies: “I should wish these Pansiesto be taken as thoughts rather than anything else: casual thoughts that are true while they are true and irrelevant when the mood and circumstance changes. I should like them to be as fleeting as pansies, which wilt so soon, and are so fascinating with their varied faces, while they last” (1Poems 671).

Individuals, for Lawrence, are mysteriously themselves, not determined as the product of their parents, and in this respect he is neither Lamarkian nor Darwinian; as he told Cynthia Asquith in 1915, “there are aristocrats and plebeians, born, not made. Some amongst us are born fit to govern, and some are born only fit to be governed […] But it is not a question of tradition or heritage. It is a question of the incontrovertible soul” (L ii. 379).

The mysterious principle of being, which for Lawrence interacts with evolutionary forces as its bride, he calls female and spatial, to evolution’s maleness and temporality:

‘Darwin and Spencer and Huxley […] these last conceived of evolution, of one spirit or principle starting at the far end of time, and lonelily traversing Time. But there is not one principle, there are two, travelling always to meet, each step of each one lessening the distance between the two of them. And Space, which so frightened Herbert Spencer, is as a Bride to us. And the cry of Man does not ring out into the Void. It rings out to Woman, whom we know not.’ (STH 97-98)

Or as he puts it in his opening paragraph: The “systole of [life’s] heart-beat is staying alive. But for the diastole of the heart-beat, there is something more […] thank heaven, than this unappeased rage of self-preservation” (STH 7). Darwin’s concept of evolution is predicated on competitive struggle, which some had described as tragic; but Lawrence’s diastole, the purpose of individuals in self-fulfillment, involves a different, wholly comedic kind of struggle.

This latter does not result in the separation and wastage of evolution’s chaff, but in life and fullness of being for both combatants (this is always a binary struggle). Lawrence adumbrates this idea in “The Crown”, in which he characterises the struggle of the royal coat of arms’s lion and the unicorn as follows:

‘There are the two eternities fighting the fight of Creation, the light projecting itself into the darkness, the darkness enveloping herself within the embrace of light […] this supreme relation is made absolute in the clash and the foam of the meeting waves. And the clash and the foam are the Crown, the Absolute. The lion and the unicorn are not fighting forthe Crown. They are fighting beneath it. And the Crown is upon their fight. If they made friends and lay down side by side, the Crown would fall on them both and kill them.’ (RDP 259)

The most wittily comic vision of such life-enabling struggle appears in Mr Noon, where it is that of the autobiographical character Gilbert Noon and his lover Johanna: “Dear Gilbert, he had found his mate and his match. He had found one who would give him tit for tat, and tittle for tattle […] The love of two splendid opposites […] all life and splendour is made up out of the union of indomitable opposites” (MN 186).

These two visions of struggle may be extended to interpretation of the much-observed heteroglossia (to use Bakhtin’s term) in Lawrence’s fiction. On the one hand, it could be argued, as Granofsky does, that Lawrence’s characters (such as Birkin and Ursula in Women in Love) argue in order to let ideas “compete for survival in his fiction”; such is “His characteristic and exploratory setting up of contrasting ideas within his works to see which would survive the competition and the frenetic revision of individual works to allow them or force them to ‘evolve’ into something ‘new’”.[34] On the other hand, this struggle between the voicers of ideas can be understood as helping each of those individuals struggle towards fullness of being. The very ambiguity here permits the systole and diastole of Lawrence’s conception of evolution – respectively phylogenic and ontogenic, tragic and comedic – to function in our act of interpretation.

It is significant that Lawrence absorbed much of his Darwinism through Hardy (who had proclaimed himself“among the earliest acclaimers of the Origin of Species”), since Hardy had been widely interpreted as tragic in his response to Darwin.[35] Lawrence’s response to Hardy’s response, however, downplayed the nature of the tragedy involved in the latter. To understand this, is it necessary to remember that Lawrence typologised tragedy. In his response to Hardy, he split the concept into lesser, life-restricting tragedy (into which category he put Hardy’s own, society-related tragedies), the greater, Nietzschian, life-affirming tragedy (which consists in conscious violation of “the greater, uncomprehended morality, or fate” or “the judgment of their own souls, or the judgment of eternal God”, and which Hardy’s but not Shakespeare’s or Sophocles’s heroes fail to reach), and the merely “little tragedy” of failing to reach individual flourishing (which is implicit in Hardy’s protagonists, but which is overshadowed for readers by the showy tragedy of these characters’ downfalls) (STH 29–30).

Lesser, social tragedy is generated by characters falling into the gap between the diastole and the systole – between fullness of being, at which they make an attempt, and the “larger scale self-preservation mechanism”, which is society. They violate the latter in their attempt, but eventually they capitulate to it and therefore die: “And from such an outburst the tragedy usually develops. For there does exist, after all, the great self-preservation system, and in it we must all live.” Their tragedy occurs “because they must subscribe to the system in themselves. From the more immediate claims of self-preservation, they could free themselves […] trying to break forth from it, died of fear, of exhaustion, or of exposure to attacks from all sides, like men who have left the walled city to live outside in the precarious open. This is the tragedy of Hardy” (STH 20-21).

It follows that Lawrence, in contrast to many of Hardy’s critics, implicitly rejects the existence of a pseudo-biological Darwinian dimension to Hardy’s tragedies, for example the genetic curse on the Fawleys, which prevents them from making successful marriages, or the family degeneracy, which afflicts Tess Durbeyfield. Rather, Lawrence renders Hardy’s Darwinism as social Darwinism, and his protagonists as victims not of biological, but social forces.

Such small-scale tragedy as is involved in their downfall is subsumed, in Lawrence’s conception, by the eternally-generative principle, which is comedic. He adumbrates this conception with regard to The Return of the Native’s (1878) Egdon Heath. Itproduces crops of infinite variety, in the plants and animals (including people) who live on it – and in certain of them it provides the impulse of passion, “the deep, rude stirring of the instincts” (STH 25). The Heath is, in Tennyson’s terms, “careless of the single life”,[36] but such tragedies are trivial in comparison to the fact that: “Egdon, the primal impulsive body would go on producing all that was to be produced, eternally, though the will of man should destroy the blossom yet in bud, over and over again” (STH 28).

‘Its crop of characters are one year’s accidental crop. What matter if some are drowned or dead, and others preaching or married: what matter, any more than the withering heath, the reddening berries, the seedy furze and the dead fern of one autumn of Egdon. The Heath persists. Its body is strong and fecund, it will bear many more crops beside this.’ (STH 25)

Egdon Heath is, therefore, the precursor of the “non-human mystery” perceived by Birkin, in the Alps, in the presence of Gerald’s corpse (WL478).

This Darwinian apprehension of a universe in which man is neither the measure nor the telos, and its apprehension as comedic, is described by Margot Norris as standing in a “biocentric tradition”, running from Darwin through Nietzsche, Kafka, and Ernst to Lawrence.[37] Darwin had “collapsed the cardinal distinctions between animal and human, arguing that they exhibit intellectual, moral, and cultural differences in degree only, not in kind.”[38] One comedic, optimistic response to this is that indicated in Tennyson’s exhortation to mankind to “Move upward, working out the beast,/And let the ape and tiger die”.[39] The other is that of the biocentric writers, who write “as the animal – not like the animal, in imitation of the animal – but with their animality speaking. I will treat Charles Darwin as the founder of this tradition, as the naturalist whose shattering conclusions inevitably turned back upon him and subordinated him, the human being, the rational man, the scientist, to the very Nature he studied.”[40]

Norris uses neither the term tragic nor comedic in her description of biocentrism. But in Lawrence’s case, I would argue, the comedic is decisively emphasised. For him, to fulfill oneself in animal, corporal being, in contact with and responsive to the rest of the universe, is a triumph and a joy: ‘We ought to dance with rapture that we should be alive and in the flesh, and part of the living, incarnate cosmos’ (A 149).

This is apparent in the argument between Clifford and Constance Chatterley, in which the former recommends a “scientific-religious” writer he is reading, who argues that evolution is successfully abstracting mind from body. He quotes: “The universe shows us two aspects: on one side it is physically wasting, on the other it is spiritually ascending […] It is thus slowly passing, with a slowness inconceivable in our measures of time, to new creative conditions, amid which the physical world, as we at present know it, will he represented by a ripple barely to be distinguished from nonentity.” Constance responds: “‘What silly hocus-pocus! As if his little conceited consciousness could know what was happening as slowly as all that! It only means he’s a physical failure on the earth, so he wants to make the whole universe a physical failure. Priggish little impertinence!’[…] ‘The life of the body,’ he said, ‘is just the life of the animals.’ […] ‘And that’s better than the life of professional corpses’”, Constance returns (LCL 233, 234).

Degeneration and Fictional Eugenics

In fact, in several of Lawrence’s fictions following Women in Love,individuals who do not unfold their buds become literally corpses – for example Banford in “The Fox” and Mrs Hepburn in The Captain’s Doll. Granofsky argues that Lawrence made death a signifier of lack of vitalistic power in reaction to the stress placed on him by the War. He further argues that whereas Lawrence, in “The Novel”, charged that Tolstoy killed off his quick characters, “Lawrence, on the other hand, will kill off his unquick characters in a fictional program of eugenics.”[41] On Granofsky’s analogy, Lawrence is functioning less as a Darwinian force of natural selection, than as a breeder practising human selection – only in his case, not in order that the unfit should not reproduce, but that their lack of vitality might be rhetorically stressed, and a form of poetic justice imposed.

These characters’ lack of tragic stature is stressed by the fact of their death. In the terms of Study of Thomas Hardy, theirs are the “little” tragedies of failing to come into full being, which are none the greater for their protagonists’ biological deaths. Their deaths do not evoke pity, any more than Malthus had pity for his surplus – and they do not render their fictional universes tragic, still less imply a real tragic universe outside of themselves. One indication of the degeneracy, in Lawrencian terms, of Beldover society is its misapplication of the term “tragedy” to the drowning of Laura Crich in a boating accident: “Such a tragedy in Shortlands, the high home of the district!” (WL 190) This is a dig both at the Classical association of tragedy with high birth, and at the application of the term “tragedy” to the accidental death of the young, which was one development of the term’s extension from art to life in the late nineteenth century.[42]

Darwin did not, unlike Haeckel, accept the possibility of biological devolution, but did, in The Descent of Man, suggest that a society could degenerate through the loss of intellectual and moral faculties: “It is most difficult to say why one civilised nation rises, becomes more powerful, and spreads more widely, than another; or why the same nation progresses more quickly at one time than at another. We can only say that it depends on an increase in the actual number of the population, on the number of men endowed with high intellectual and moral faculties.”[43] Accordingly, he speculates that one possible reason for the degeneration of the Greeks was “extreme sensuality”, for they did not succumb until “they were enervated and corrupt to the very core.”[44]

For Lawrence, almost exactly the reverse was the case; it was through the over-development of the mental faculties, in detachment from sensual reality, that individuals and their societies become degenerate. In his meditation on the Book of Relevations, Apocalypse, Lawrence presents as evidence of human devolutionthe fact that humans now smirk at “the riddle of the sphinx about legs”, which “seems to us silly”. He argues that to its original audiences, “The thing that goes on four legs is the animal, in all its animal difference and potency, its hinterland consciousness which circles round the isolated consciousness of man” (A 92). Despite Darwin’s recent impact at an intellectual level, Lawrence diagnoses that humanity has disastrously lost its sense of kinship with animals at a deeper level. In “Him With His Tail in His Mouth”, Lawrence tracks human devolution in terms of its ability to depict animals in art:

‘how did those prognathous semi-apes of Altamira come to depict so delicately, so beautifully, a female bison charging […] It is art on a pure, high level, beautiful as Plato, far, far more “civilized” than Burne-Jones. – Hadn’t somebody better write Mr Wells’ History backwards, to prove how we’ve degenerated, in our stupid visionlessness, since the cave-men?’

The pictures in the cave represent moments of purity which are the quick of civilization. The pure relation between the cave-man and the deer: fifty per-cent man, and fifty per-cent bison, or mammoth, or deer. It is not ninety-nine per-cent man, and one per-cent horse: as in a Raphael horse. Or hundred per-cent fool, as when G.F. Watts sculpts a bronze horse and calls it Physical Energy (RDP 316-17).

Lawrence, like both Nietzsche and Nordau, thought that one index of European civilisation’s degeneration was its perverse conception not just of civilisation, but of evolution itself. This is apparent in the argument between Clifford and Constance Chatterley quoted above. Clifford tells his wife, who informs him that she has been dancing naked in the rain, “You’d have no need to cool your ardent body by running out in the rain, if only we have a few more aeons of evolution behind us”. Constance dismisses this conception as “spiritually blown out” (LCL 233).

When degenerate characters predominate in a civilization, as they do in Women in Love, then that civilization is itself in decline – yet the fact of its degeneration is no more tragic than are the deaths of its members. Other civilizations, such as those of Russia, the United States or Mexico, will rise to take the place of the European civilization that is, in Lawrence’s conception, committing slow suicide in the First World War. In his 1919 Preface to S.S. Koteliansky’s translation of Shestov’s The Apotheosis of Groundlessness, he writes that when Russia frees itself from European influence, “Russia will certainly inherit the future” (IR 5). In Studies in Classic American Literature he asserts that “Two bodies of modern literature seem to me to have come to a real verge: the Russian and the American”; they contain “a quick. From which the future may develop” (SCAL 389-90). The Plumed Serpent describes the re-ascendance of Mexican over European civilization through an Aztec revivalist cult.

The same applies to humanity itself. Since, for Lawrence, the individual is more important than the collective, the extinction of humanity can be no more tragic than can that of an individual; as Birkin asserts, “Humanity is less, far less than the individual, because the individual may sometimes be capable of truth, and humanity is a tree of lies” (WL126).The hypothesis of eventual human extinction had gained considerable credibility from Darwin, as Granofsky points out.[45] In 1862, Herbert Spencer wrote in First Principles that dissolution is “apt to occur when social evolution has ended and decay has begun”; “are we not manifestly progressing towards omnipresent death?”; “Is that motionless state called death, which ends Evolution in organic bodies, typical of the universal death in which Evolution at large must end? And have we to contemplate as the outcome of things, a boundless space holding here and there extinct suns, fated to remain for ever without further change?”[46] James Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890-1915), which Lawrence read in 1915, envisaged “the sun someday cooling and we all freezing”; other beings, such as the crabs that live in the far future at the end of H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine (1895), will however far outlive humanity.[47]

Lawrence’s own envisioning of human extinction was inspired by and inverted the misanthropy of the late Tolstoy. The protagonist of the latter’s 1889 novella The Kreutzer Sonata advocates sexual abstinence in the interests of spiritual salvation. When it was pointed out to Tolstoy that Pozdnyshev’s recommendations, if followed, would result in humanity dying out, Tolstoy responded:

‘What will die out is man the animal. What a terrible misfortune that would be! […] Let it die out. I am no more sorry for this two-legged animal than I am for the ichthyosaurs etc. What I care about is that the true life should not die out, the love of creatures that are able to love.'[48]

Of course, this means humanity will die out precisely by becoming more true in its loving. No such contradiction operates in Lawrence’s advocacy of the right kind of sex as assisting humans towards fulness of being. However, his lack of attachment to humanity bears striking similarities to Tolstoy’s; in “Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine” he writes: “either [man] will have to start budding, or he will be forsaken of the Holy Ghost: abandoned as a failure […] as the ichthyosaurus was abandoned” (RDP 360).

Women in Love’s Birkin also mentions the ichthyosaurus in the context of human extinction: ‘Man is one of the mistakes of creation—like the ichthyosauri […] The ichthyosauri were not proud: they crawled and floundered as we do.’ (WL 127-28)

It is unclear, as Ursula points out, how human extinction would in physical terms be brought about; the only agency that Birkin adduces is “the proud angels and the demons”. Ursula’s pessimistic understanding that humanity “could not disappear so cleanly and conveniently. It had a long way to go yet, a long and hideous way”neatly inverts Nordau’s optimistic prediction:“Humanity has not yet reached the term of its evolution […] It is still young.”[49] Nonetheless, Tolstoy and Lawrence are agreed that their vision is not tragic:“there would be no absolute loss, if every human being perished tomorrow” (WL 127).

Birkin reprises the point in the presence of Gerald’s corpse: “‘God cannot do without man.’ It was a saying of some great French religious teacher. But surely this is false. God can do without man. God could do without the ichthyosauri and the mastodon.” (WL 478). Yet this time, he couches his post-human vision in hypothetical terms: “should he too fail creatively to change and develop” (italics mine). Individuals have the means of development and flourishing in their own hands, just as in Lamarck’s understanding individuals could improve their fitness. As Granofsky notes, “Like all social Darwinists” Lawrence “was in a hurry, and concerned with what could be achieved in a lifetime”.[50] Just as nineteenth century evolutionary theories had mapped the eighteenth century conception of evolution in relation to ontogeny onto phylogeny, social Darwinists (including, in a broad sense of that term, Lawrence) mapped phylogeny back onto ontogeny, and the possibility of development within a lifetime. Were it otherwise, Lawrence’s preaching, in this novel and his other works, would on its own terms be without point.

It is, according to Lawrence, possible to live in contact with what Apocalypse calls “that in the cosmos which contains the essence, at least, or the potentiality, of all things”; as Constance tells Clifford, “I feel that whatever God there is has at last wakened up in my guts, as you call them, and is rippling so happily there” (A 17, LCL 235). Constance’s is not an eternal, static comedy like that of the saved of the New Jerusalem inRevelations according to Apocalypse, but a firmly sublunary comedic vision. As Lawrence puts it in “Him With His Tail in His Mouth”: “I don’t want eternal life, nor length of days for ever and ever. Nothing so long drawn out. I give up all that sort of stuff. Yet while I live, I want to live” (RDP 311).

Gerald Crich’s Darwinian Tragi-Comedy

Gerald Crich therefore suffers a “barren tragedy”, which owes much to Lawrence’s revisionary response to Darwin. He failed to develop himself, and in this sense his is a “little” tragedy. He partly but not fully broke with society in his relationship to Gudrun, and in this sense suffers a “lesser” tragedy – not tragedy in a positive Nietzschian sense, nor in the sense described approvingly in the Preface to Touch and Go as involved in “a struggle we were convinced would bring us to a new freedom” (Plays 367). He is, in a very different sense to Lawrence himself, a social Darwinist, and is therefore in Lawrence’s terms degenerate. Having visited South America as a young man, as did Darwin in the 1830s, Gerald like Darwin likened the natives to children.[51] He did not, like Lawrence in The Plumed Serpent and other of his American writings, perceive ways in which native Americans might inherit the future.

A mine-owner, and mechaniser of his mines, he was thrown up by the systole of social evolutionary imperative as manifested in industrialisation, but failed fatally at the level of diastole. In “Education of the People”, Lawrence asserts that in “disintegrating periods” of history, man becomes “a unit of automatised existence” symbolised by “the great man who represents the wage-reality” who is “hailed as the supreme” (RDP 110). This description fits Gerald, who becomes a mechanical man, and therefore subject to the laws of physics rather than biology. As Ebbatson points out, “Laws of evolution suggest unbroken continuity, but laws of physics may hint at stopping or entropy”.[52] At one point in the novel, Gerald is described as “suspended motionless, in an agony of inertia, like a machine that is without power […] Now, gradually, everything seemed to be stopping in him” (WL 266). Ebbatson suggests that he is therefore an ironic representation of maximally-evolved man: “From the primal homogeneity of the early Brangwens, mankind’s yearning for development culminates, at one level of meaning, on the Alpine heights […] The characterisation of Gerald represents the Lawrencian critique of Spencer’s theory of the gradual disappearance of imperfection, and his positivist claim that \the ultimate development of the ideal man is logically certain.’”[53]

On the other hand, as I and others have argued, Gerald has something of the aspect of a scapegoat.[54] He was someone who was capable of more, as Birkin perceives: “He might have gone on […] He might! […] If he had kept true to that clasp, death would not have mattered” (WL 478, 480). Birkin is comforted by his vision of “the timeless creative mystery” (“It was very consoling to Birkin, to think this”) – but he is in great need of comfort: “Either the heart would break, or cease to care. Best cease to care” (WL 479).

Whatever the non-human comedic universe envisioned by Birkin, and by Lawrence in so many of his works – and however much the amplitude of Gerald’s tragedy is circumscribed by his own failings – the feeling of the novel’s ending is at best tragi-comic (in the sense of the commingling of these genres). Despite the treatment of Banford in “The Fox”, and Mrs Hepburn in The Captain’s Doll, it is not the case that all of Lawrence’s characters who freeze in their development, as Crich freezes in the snow, “are abandoned by their creator”, as Granofsky asserts.[55] Michael Bell, when he describes the novel a “psychomachia in which the major figures are potentialities of each other”, rightly observes that “If they do indeed grow apart it is by a tragic wrenching.”[56]

Gerald’s death is not followed by a decisive comedic ending for the novel’s other couple, Birkin and Ursula, such as Anna Karenina affords to Levin and Kitty. Their ending is certainly not that of the saved in the New Jerusalem, as contrasted to the burning lake of, say, Dresden (whither Gudrun travels with Loerke). Ebbatson judges rightly that the emotional impact of Gerald’s tragedy has been so strong that the final scene of the surviving couple functions “like the close of a Shakespearean tragedy, both mourning the past and looking to a reconstructed future.”[57] Moreover, the novel contains so many characters who fail creatively to develop that there is force to Ebbatson’s argument that, whereas the progress of The Rainbow is evolutionary, that of Women in Loveis degenerative.[58]

Rather, Birkin and Ursula’s is the quieter evolutionary comedy of flux and possibility: nothing about them is fixed; and therefore they will be able to adapt and survive, overshadowed and chilled, but not frozen, by Gerald’s barren tragedy. The very fact that they finish the novel mid-argument denies the novel closure, fails to separate the novel as art from the lives of its creator and its readers, and therefore implicitly throws onto the readers the responsibility for determining its continuation – preferably by reaching that self-fulfilment which it presents as the primary end of all life. There isa way out, the novel suggests, out of the Alps, out of England, out the War, one might find it – indeed to believe this is to have found it – time has not ended, the game is never up.

NOTES

[1] For example, by Beer 1983, Ruse 2006, Richards 2008, and Bell 1992.

[2] For Darwin’s impact on Lawrence see however Ebbatson 1982, Norris 1985, and Granofsky 2003.

[3] For example see Williams 122 and Bell 105.

[4] The quotation from Tolstoy is taken by Lawrence from Gorky 19.

[5] Karl Marx wrote approvingly about Darwin to Engels in 1860, and Alfred Russell Wallace became increasingly socialist over the course of his career, whereas social Darwinists such as Herbert Spencer, Andrew Carnegie and Heinrich von Treitschke used Darwin’s theories in support of their opposition to statist attempts to abolish inter-personal and inter-group struggle; see Young 19 and Oldroyd 212-214. Gillian Beer notes the contradictory possible political deductions to be made from Darwin’s description of man: “whereas the story of man’s kinship with all other species had an egalitarian impulse, the story of development tended to restore hierarchy and to place at its apex not only man in general, but contemporary European man in particular – our kind of man, to the Victorians” 114.

[6] Beer 5.

[7] Beer 115-16.

[8] Beer 115-16, 206.

[9] Richards 11.

[10] Oldroyd 274.

[11] Richards 15-16.

[12] Nordau 540.

[13] Ruse 259.

[14] Freud 221.

[15] Darwin, The Origin of Species459-60.

[16] O’Gorman 165, 117.

[17] George Levine notes that Victorian realism started comic, but became tragic. 47.

[18] “Ours is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically. The cataclysm

has happened, we are among the ruins, we start to build up new little habitats, to

have new little hopes […] This was more or less Constance Chatterley’s position.

The war had brought the roof down over her head. And she had realised that one

must live and learn” LCL5.

[19] Dupree 273, 266, 274.

Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach” contains the lines:

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Aegean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

O’Gorman 312-13

[20] Chambers 112.

[21] Worthen 171-72, 175.

[22] Ebbatson 88.

[23] Quoted in Carroll 17.

[24] This is not to deny the complication of this account by recent explorations of Lawrence’s attraction towards the mechanics, such as Wallace 2005.

[25] Oldroyd 35.

[26] Norris 18.

[27] Norris 6-7.

[28] Ebbatson 81.

[29] Young 19.

[30] The Origin of Species460.

[31] The Origin of Species458.

[32] Young 16; Hodge and Radick 373.

[33] Granofsky 30.

[34] Granofsky6-7.

[35] Wilson 158.

[36] O’Gorman 117.

[37] Norris 1 and passim.

[38] Norris 3.

[39] O’Gorman 156.

[40] Norris, Beasts of the Modern Imagination1. Nietzsche “used Darwinian ideas as critical tools to interrogate the status of man as a natural being.”

[41] Granofsky 32, 9. He also argues: “Eventually, we get the leadership fiction, whose peculiar mixture of utopianism and misanthropy corresponds to the optimistic and pessimistic readings (towards perfection and extinction, respectively) to which the idea of evolution is open, as Gillian Beer has pointed out (16, 22, 39f et passim)” 7.

[42] James Joyce’s character Stephen Dedalus complains similarly about the debasement of the term: “A girl got into a hansom a few days ago, he went on, in London. She was on her way to meet her mother whom she had not seen for many years. At the corner of a street the shaft of a lorry shivered the window of the hansom in the shape of a star. A long fine needle of the shivered glass pierced her heart. She died on the instant. The reporter called it a tragic death. It is not. It is remote from terror and pity according to the terms of my definitions” 209.

[43] The Origin of Species 132.

[44] The Descent of Man 177-78; Darwin gives his quotation as from “Mr. Greg, ‘Fraser’s Magazine,’ Sept. 1868, p. 357”.

[45] Granofsky 30.

[46] Spencer 416, 413, 423-24.

[47] Ebbatson 107.

[48] Tolstoy 12.

[49] Nordau 540.

[50] Granofsky 15.

[51] Gerald describes the “savages” as “on the whole” “harmless – they’re not born yet, you can’t feel really afraid of them. You know you can manage them” (WL66). This echoes the tone in parts of Darwin’s The Voyage of the Beagle, which Lawrence had read:“I just read Darwin’s Beagle again” (L vi. 214).

[52] Ebbatson 106.

[53] Ebbatson 107-08.

[54] See Brown 135 ff. Roger Ebbatson argues that Gerald has “a sacrificial role: a man personifying a late stage of industrial power and organisation through the dominance of the will”, 109.

[55] Granofsky 23.

[56] Bell 105.

[57] Ebbatson 109.

[58] Ebbatson xix.

WORKS CITED

Arbery, Glenn, ed., The Tragic Abyss (Dallas: The Dallas Institute of Humanities and

Culture, 2003)

Beer, Gillian, Darwin’s Plots: Evolutionary Narrative in Darwin, George Eliot and

Nineteenth-Century Fiction (London, Boston, Melbourne and Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1983)

Bell, Michael. 1992. D.H. Lawrence: Language and Being (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press)

Brown, Catherine, The Art of Comparison: How Novels and Critics Compare

(London: Legenda, 2011)

Carroll, David, George Eliot and the Conflict of Interpretations (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1992)

Chambers, Jessie, D.H. Lawrence: A Personal Record (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1980)

Darwin, Charles, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 1981)

Darwin, Charles, The Origin of Species (London: Penguin, 1985)

Darwin, Charles, The Voyage of the Beagle (1839)

Dupree, Robert S., ‘Alternative Destinies: The Conundrum of Modern Tragedy’, in Glenn Arbery, ed., The Tragic Abyss(Dallas: The Dallas Institute of Humanities and

Culture, 2003), pp. 273 onwards

Ebbatson, Roger, The Evolutionary Self: Hardy, Forster, Lawrence (Brighton,

Sussex: Harvester Press, 1982)

Gorky, Maxim, Reminiscences of Leo Nicolayevitch Tolstoi, trans. S.S. Koteliansky

and Leonard Woolf (London: Hogarth Press, 1934)

Granofsky, Ronald, DH Lawrence and Survival: Darwinism in the Fiction of the

Transitional Period (Montréal and London: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003)

Hodge, Jonathan and Gregory Radick, eds, The Cambridge Companion to Darwin, 2nd

edn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009)

Joyce, James, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (London: Paladin, 1988)

Levine, George, ‘Hardy and Darwin: An Enchanting Hardy’, in Keith Wilson, ed., A

Companion to Thomas Hardy (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), pp. 37 onwards

Nietzsche, Friedrich, The Birth of Tragedy, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York:

Vintage Books, 1967)

Nordau, Max, Degeneration (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press,

1995)

Norris, Margot, Beasts of the Modern Imagination: Darwin, Netzsche, Kafka, Ernst,

and Lawrence (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985)

Oldroyd, D.R., Darwinian Impacts: an Introduction to the Darwinian Revolution

(OUP, Milton Keynes, 1980)

Richards, Robert J., The Tragic Sense of Life: Ernst Haeckel and the Struggle over

Evolutionary Thought (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2008)

Ruse, Michael, Darwinism and its Discontents (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2006)

Tennyson, Alfred, Poetical Works of Alfred Lord Tennyson (New York: Macmillan,

1899)

Tolstoy, Lev, The Kreutzer Sonata and Other Stories, trans. by David Mcduff

(London: Penguin, 1983)

Wallace, Jeff, D.H. Lawrence, Science and the Posthuman (Basingstoke: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2005)

Williams, Raymond, Modern Tragedy (London: Chatto and Windus, 1966)

Wilson, Keith, A Companion to Thomas Hardy (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell , 2009)

Worthen, John, D.H. Lawrence: The Early Years 1885-1912 (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1991)

Young, Robert M., Darwin’s Metaphor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1985)

ABBREVIATIONS

Letters of D. H. Lawrence

1L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume I: September 1901–May 1913, ed. James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1979).

2L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume II: June 1913–October 1916, eds. George J. Zytaruk and James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1981).

3L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume III: October 1916–June 1921, eds. James T. Boulton and Andrew Robertson (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1984).

4L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume IV: June 1921–March 1924, eds. Warren Roberts, James T. Boulton and Elizabeth Mansfield (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1987).

5L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume V: March 1924–March 1927, eds. James T. Boulton and Lindeth Vasey (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1989).

6L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume VI: March 1927–November 1928, eds. James T. Boulton and Margaret H. Boulton with Gerald M. Lacy (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1991).

7L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume VII: November 1928–February 1930, eds. Keith Sagar and James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1993).

8L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume VIII: Previously Uncollected Letters and General Index, ed. James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000).

Works of D. H. Lawrence

A Apocalypse and the Writings on Revelation, ed. Mara Kalnins (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1980).

AR Aaron’s Rod, ed. Mara Kalnins (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988).

BB The Boy in the Bush, with M. L. Skinner, ed. Paul Eggert (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990).

EmyE England, My England and Other Stories, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1990).

FLC The First and Second Lady Chatterley Novels, eds. Dieter Mehl and Christa Jansohn (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1999).

Fox The Fox, The Captain’s Doll, The Ladybird, ed. Dieter Mehl (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992).

FWL The First ‘Women in Love’, eds. John Worthen and Lindeth Vasey (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1998).

IR Introductions and Reviews, eds. N. H. Reeve and John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005).

K Kangaroo, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1994).

LAH Love Among the Haystacks and Other Stories, ed. John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1987).

LCL Lady Chatterley’s Lover and A Propos of ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’, ed. Michael Squires (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1993).

LEA Late Essays and Articles, ed. James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004).

LG The Lost Girl, ed. John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1981).

MEH Movements in European History, ed. Philip Crumpton (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1989).

MM Mornings in Mexico and Other Essays, ed. Virginia Crosswhite Hyde (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009).

MN Mr Noon, ed. Lindeth Vasey (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1984).

Plays The Plays, eds. Hans-Wilhelm Schwarze and John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1999).

PM Paul Morel, ed. Helen Baron (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003).

PO The Prussian Officer and Other Stories, ed. John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1983).

1Poems, 2Poems, 3Poems The Poems. 3 Vols., ed. Christopher Pollnitz (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2013).

PS The Plumed Serpent, ed. L. D. Clark (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1987).

PFU Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004).

Q Quetzalcoatl, ed. N. H. Reeve (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2011).

Paintings The Paintings of D. H. Lawrence(London: Mandrake Press, 1929).

R The Rainbow, ed. Mark Kinkead-Weekes (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1989).

RDP Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays, ed. Michael Herbert (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988).

SCAL Studies in Classic American Literature, eds. Ezra Greenspan, Lindeth Vasey and John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003).

SEP Sketches of Etruscan Places and Other Italian Essays, ed. Simonetta de Filippis (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992).

SL Sons and Lovers, eds. Helen Baron and Carl Baron (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992).

SM St. Mawr and Other Stories, ed. Brian Finney (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1983).

SS Sea and Sardinia, ed. Mara Kalnins (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997).

STH Study of Thomas Hardy and Other Essays, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1985).

T The Trespasser, ed. Elizabeth Mansfield (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1981).

TI Twilight in Italy and Other Essays, ed. Paul Eggert (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1994).

VicG The Vicar’s Garden and Other Stories, ed. N. H. Reeve (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009).

VG The Virgin and the Gipsy and Other Stories, eds. Michael Herbert, Bethan Jones and Lindeth Vasey (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006).

WL Women in Love, eds. David Farmer, Lindeth Vasey and John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1987).

WP The White Peacock, ed. Andrew Robertson (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1983).

WWRA The Woman Who Rode Away and Other Stories, eds. Dieter Mehl and Christa Jansohn (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1995).