Report of the Thirty-Fourth Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Terry Gifford

Lawrence, Sardinia and Ecology

Thursday 18th April 2024

By Zoom

18.30-20.00 UK time

ATTENDERS

30 people attended, including, from outside of England, Philip Chester in Deep River, Ontario, Jim Phelps in Cape Town, Vic West in Aichtal near Stuttgart, Lee Jenkins in County Cork, Jeffrey McCarthy in Corsica, Carrie Rohman in Pennsylvania, Keith Cushman in North Carolina, and Ben Hagen in Vermillion, South Dakota

INTRODUCTION

‘When last autumn I made this presentation in Spain to Xavia Book Circle one person was outraged that Lawrence could make judgements about the Sardinians from a nine-day train and bus journey across the island. Fair enough. But what is fascinating about those judgements of the character of different people in different parts of the island is that they are based upon the affect of the ecology of place. Sea and Sardinia is a contentious and cantankerous, playfully provocative work of psychogeography that deserves to be taken seriously. In June 2023 Gill and I retraced Lawrence’s journey backwards towards a conference at the University of Cagliari celebrating the book Insights into D. H. Lawrence’s Sardinia (2022). We were surprised to meet Lawrence unexpectedly in two places along the way, as this illustrated presentation reveals.’

BIOGRAPHY

Terry Gifford is the author of D. H. Lawrence, Ecofeminism and Nature (2023). He is Visiting Research Fellow at Bath Spa University’s Research Centre for Environmental Humanities, UK and Professor Honorifico at the Universidad de Alicante, Spain. A co-founder of British ecocriticism, he is the author of Pastoral (2020), Green Voices (2011), Ted Hughes (2009) and Reconnecting With John Muir (2006). He is currently editing Reading D. H. Lawrence in the Anthropocene for Edinburgh University Press and writing an ecofeminist reading of Lawrence’s short stories.

PRESENTATION

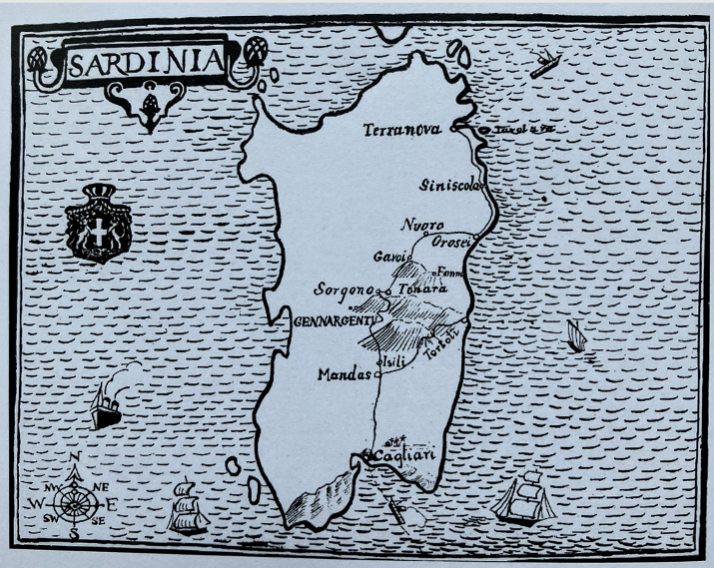

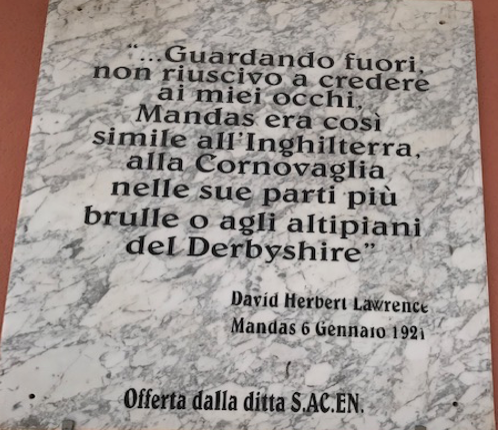

Terry gave an account of his and his wife’s 2023 reverse (North to South) retracing of the Lawrences’ 1921 journey across Sardinia, which entailed reading Sea and Sardinia in reverse. Lawrence’s descriptions are sufficiently precise that they were able to identify many of the locations, and to photograph them. They also discovered that, being confined to train and bus transport, the Lawrences had been unable to visit signs of the 2000 year-old culture of Sardinia; he and his wife visited granite monoliths and dolmen. Terry opened with the observation that whereas in Twilight in Italy nature and culture are separately described, in Sea and Sardinia they are mutually influential; indeed, landscape affects people more than the reverse is true. The book dramatizes – and sometimes comically exaggerates – Lawrence’s response to the landscape, which he views as though from a distance, and as though his travelling is being directed by Frieda. Having been affected by (in the words of the book’s famous opening) ‘an absolute necessity to move’, he chooses to move away from Sicily’s expats to a less inhabited, less civilised environment, replacing Etna by the lesser-known Gennargentu mountains. Choosing to take a narrow gauge railway over the mountains to Nuoro and then Terra Nova (now Olbia), he developed a theory of the psychogeography of the mountains compared to the plains, considering that the ‘life-level’ is better in the mountains, and that there are people are tougher, in a good way. Terry considered that in the book Lawrence anticipated biosemiology. He also developed his ‘psyche of islandness’ (this being a topic found in many of his writings). Clearly, he was experiencing nostalgia for the bleakness of the Cornish landscape, and as this quotation – presented in Italian on a plaque in Mandas – states, Sardinia reminded him of it.

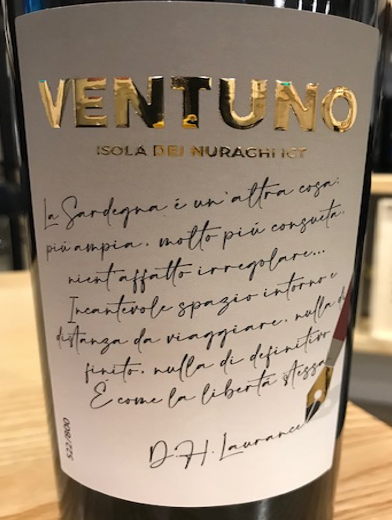

Sardinians today are well aware of the book. There is a statue and a bust of him at the train station at Mandas. At Sorgorno the restauranteurs celebrate Lawrence despite the way he described their establishment, and sell Lawrence merchandise:

Terry concluded by arguing that Sea and Sardinia is a rehearsal for the essays and stories of Lawrence New Mexican period. The book makes one mention of a Pan, which is considerably expanded upon in the New Mexican context.

DISCUSSION

Dudley Nichols was puzzled by the time of year that Lawrence chose to visit Sardinia; they left Sicily on 4th January, and the narrative is driven by the freezing conditions in their hotels. Terry agreed that Lawrence would have responded very differently in the spring; there are very few references to flowers; but Lawrence also responds positively to the cold, because of its conformity with the wildness which he was seeking. John noted that Lawrence wrote no letters or postcards in Sardinia, and that he was clearly being physically challenged. Terry agreed, noting that the Lawrences were moving every day, using an out-of-date Baedeker, arriving late in each place, and then having to find accommodation. He didn’t even write any notes from which Sea and Sardinia might have been drawn; it is exceptional that he wrote nothing for nine days; he wrote the book from memory upon return to Taormina.

Jeffrey asked Terry to compare Lawrence’s response to the Sardinian landscape to Auden’s poem ‘In Praise of Limestone’ of a few decades later. Terry replied that Lawrence became critical of lowland, coastal culture, and approving of the way in which the granite and its ecology made people independent, and relatively equal with regard to class (he notes that a maid in Cagliari is treated as a member of the family).

Keith Cushman asked what Terry thought of Jan Juta’s illustrations to the book, which he made after a trip to the island, but without reading what Lawrence had written about it, resulting in an interesting gap between the narrative and the paintings. Terry said that liked them as combining modernist style with traditional content, such as local costumes; he also noted that Jonathan Long has written a chapter about them (as had Keith himself).

Carrie Rohman noted that Lawrence’s contradictions, for which he is famed, and which make him lovable, are abundantly represented in the book. Terry thought that these contributed to its freedom and freshness; Lawrences dramatizes his contradictions, and repeatedly admits that he might not be right. Jim Phelps noted Lawrence’s dramatization of himself and his wife as characters; Terry responded that even first-person pronouncements such as ‘I don’t believe there were ever any Celts’ are self-distanced. Jonathan Long described this as ‘easy, approachable humour’, making Sea and Sardinia a good introduction to Lawrence for anyone who had never read any. Terry thought that this humour and ease constituted one of the differences in tone to the later Mexican essays, and that what Lawrence was searching for in Sardinia, he found in the New Mexican Indians. Lee Jenkins noted that it was, in fact, when Mabel Dodge Luhan read excerpts in The Dial, that she invited Lawrence to visit her in New Mexico.

Terry concluded by pointing to how much Sea and Sardinia had to say on the environmental crisis that we are currently living through. The whole book is about how people have accommodated to their environment, living in and of the place rather than just resting on its surface.