Report of the Thirty-Third Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Philip Chester

Tit & Tat: A Tale of Two Alley Cats: Aldington and Lawrence

Thursday 28th March 2024

By Zoom

18.30-20.00 UK time

ATTENDERS

27 people attended, including, from outside of England, Philip Chester in Deep River, Ontario, Lorne Chester in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, Robert Bullock in Paris, Shirley Bricout in Vannes, Brittany, Lee Jenkins in County Cork, Jim Phelps in Cape Town, Shanee Stepakoff in Connecticut, and Phil Bufithis in the US.

INTRODUCTION

This presentation surveyed the evolution of the relationship between D. H. Lawrence and Richard Aldington between 1914 and 1928, analysing the nature of their friendship, the reasons why it apparently broke down on Port-Cros in 1928, and such positive feelings as managed to survive this rupture.

READING

The period which Lawrence and Aldington spent together on the island of Port-Cros from 15th October – 17thNovember 1928 is covered by pp. 590-618 of Volume 6 of the Cambridge University Press edition of the Letters, whilst the opening of Volume 7 contains letters sent immediately after Lawrence’s return to the mainland.

BIOGRAPHY

Philip Chester is a retired teacher and independent scholar living in Deep River, Ontario, Canada – roughly a ten-day canoe paddle northwest of Ottawa on the Kitchissippi (Ottawa) River. He has a B.A. in English from Carleton University in Ottawa (1974) and a B.Ed. from the University of Toronto (1978). His literary interests other than Lawrence include Canadian wilderness literature, Lawrence Durrell, Dylan Thomas, and, most recently, Richard Aldington.

PRESENTATION

Philip started by acknowledging that he was speaking from the traditional lands and unceded territory of the Algonquin People.

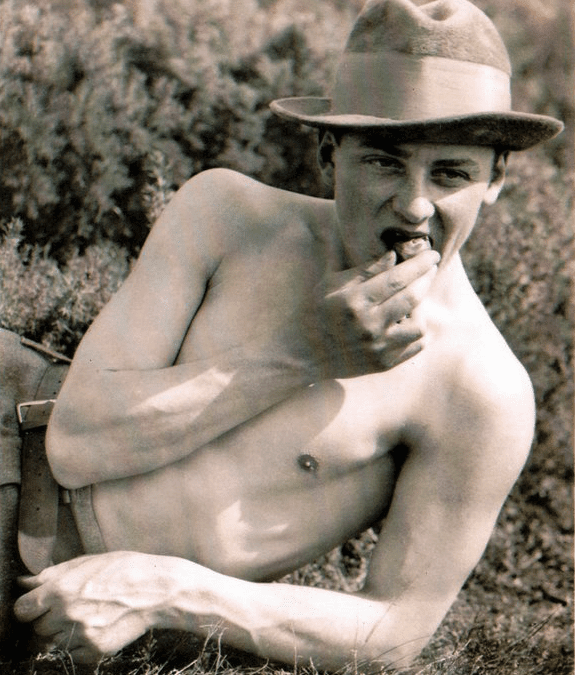

He explained the title of his talk as paying reference both to the ‘tit for tat and tittle for tattle’ sequence describing the relationship of the lovers in Mr Noon, and to the epilogue ‘Enter Bim and Bom’ of Aldington’s 1931 novel The Colonel’s Daughter. He gave a brief biography of Aldington, covering his autodidacticism, Classical studies, marriage to the American poet H. D., co-creation of imagist poetry, war service in France, time in Berkshire with his lover Arabella Yorke, relationships with other women, ascension to fame with his novel Death of a Hero in 1929, and later life. He then surveyed his (at times strained) friendship with D. H. Lawrence.

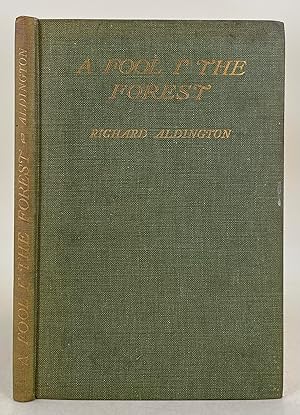

The men were introduced by Amy Lowell in London in 1914, met again in Chesham, Berkshire, and in 1915 briefly lived near one another on Hampstead Heath. In 1917 they cohabited in 44 Mecklenburgh Square after the Lawrences were expelled from Cornwall, and met several times more until 1919, after which their contact reduced. In 1926 it revived when Lawrence visited Aldington in Berkshire during his last trip to England, and Aldington returned with a visit to Lawrence in Italy. In 1927 Aldington wrote D. H. Lawrence: An Indiscretion. This was followed in 1928 by a month of worsening relations when they lived – along with Arabella Yorke, Brigit Patmore and Frieda – on the island of Port-Cros in South France. Aldington described this time as involving a ‘series of demented scenes out of some southern Wuthering Heights’. After they parted on November 17th 1928 Aldington wrote to H. D.: ‘I hope I never see him again’. He didn’t, nor did he ever receive another letter from Lawrence. Yet Aldington did visit Sylvia Beach in Paris to see whether she would publish a cheap authorised edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover; after Lawrence’s death he renamed D. H. Lawrence: An Indiscretion as D. H. Lawrence: An Appreciation; he several times wrote positively about Lawrence, and this culminated in his 1950 biography Portrait of a Genius, But.

Philip presented both men as damaged: Lawrence by his adverse childhood experiences, chronic sickness, and the War; Aldington by his adverse childhood experiences, the stillbirth of his and H. D.’s baby, and the War. He identified multiple possible reasons for Lawrence’s attacks on Aldington during their time on Port-Cros, including the contrast posed by Aldington’s potency to his own sickliness, the distress caused by Aldington to Lawrence’s friend Arabella Yorke by starting a relationship with Brigit Patmore, a possible affair between Frieda and Aldington, and Frieda’s approval of Aldington’s emerging novel Death of a Hero, which contained a negative representation of Lawrence as Mr Bobbe. Philip argued that Lawrence’s poem ‘A Noble Englishman’, which was later published in Pansies, represented Aldington as homosexual. With regard to the deteriorating friendship, he apportioned blame to both sides, but particularly thought that Lawrence should have been more understanding of Aldington’s suffering from shell shock.

DISCUSSION

David Ellis pointed out that both men accused the other of being homosexual types; and that this was extraordinary coming from Lawrence, who was so often himself thus accused. He noted that it was on Port-Cros that Lawrence first obtained definitive proof (from a letter) that Frieda was having an affair (with Ravagli), although he had likely suspected it before, and that this would have soured his mood further. He also thought that Lawrence was irritated by Aldington’s aspect as a ‘war hero’. He wondered whether, if Aldington had read ‘A Noble Englishman’ (which Lawrence wrote on Port-Cros), this might have provoked his negative representation as Mr Bobbe in Death of a Hero. Philip responded that Aldington’s biographer, Vivien Whelpton, thought this was the case. John Worthen responded that the poem’s ink colour indeed indicates that it was written on Port-Cros; it was unlikely that Lawrence would have showed it to him himself, but any one of the three women on the island might have done so. Lee Jenkins suggested that Death of a Hero’s encomium to ‘D. H. Lawrence’ indicated a split between Aldington’s response to Lawrence as a person (caricatured as Bobbe), and as a writer. She also speculated that, with Bobbe, Aldington was upping the ante from Huxley’s (relatively positive) representation of Lawrence as Rampion in Point Counter Point.

Max Saunders argued that writers in this period habitually represented one another satirically, and that a willingness to analyse each other’s problematic sides may have indicated a kind of integrity in friendship; Aldington’s book Soft Answers does this with T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and all those whom he knew best. Such treatments could help develop their targets; Aldington was not diminished by Lawrence’s attacks on him, but rather became a successful novelist. F. M. Ford and Ernest Hemingway performed a similar function for each other. David Ellis disagreed, arguing that the targets strongly objected to such treatment (Michael Arlen’s representation as Michaelis in Lady Chatterley’s Loverbeing a notable exception). Lee Jenkins agreed with Max that ‘literary backbiting’ was an understood feature of fiction in this period, with H. D.’s 1960 novel Bid Me to Live (treating Lawrence and Aldington amongst others) being a late example. David agreed that such treatments were common but not that they were acceptable (recalling Norman Douglas’s opinion that duelling should be re-introduced). He added the stakes involved in representing someone as homosexual, when such activity was illegal and strongly punished, were high.

After the meeting, Robert Bullock added to the discussion by email to the effect that Lawrence’s jealousy of Arabella’s, Brigit’s and Frieda’s praise of the emergent Death of a Hero was likely an important factor in his rising anger at Aldington, given how jealous he had already been made by the success of Point Counter Point; he did not exhibit such jealousy towards friends (such as Mark Gertler) who were not writers. Vic West thought that some of the citations from Lawrence’s letters to Aldington, which Philip had adduced as manifesting hostility, might also have manifested affection (for example the phrase ‘What ails thee lad?’). On Aldington’s side, his advocacy for Lawrence following the latter’s death may have been motivated by intellectual integrity and respect for Lawrence’s achievements. Catherine Brown agrees with Vic on the first point; when Lawrence wrote to Aldington from Villa Mirenda on 18th November 1927: ‘Awfully nice of you to offer an egg from your ill-laying goose. But I’m not hard-up – and when I am, if ever I am, I’ll make richer people fob out’, this was not a swipe at Aldington for relative poverty but can be taken at face value.