Report of the Thirty-Sixth Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Blake Matich

An Unprofessional Lecture: Anaïs Nin, D.H. Lawrence and Proceeding by Intuition

Thursday 27th June 2025

By Zoom

18.30-20.00 UK time

ATTENDERS

20 people attended, including, from outside of England, Catherine Brown in Germany, Berna Uysal in Paris, Tim Gupwell in Perpignan, Shirley Bricout in Brittany, Kathleen Vella in Malta, Philip Chester in Deep River, Ontario, Shanee Stepakoff in Connecticut, Jim Phelps in Cape Town, and Yup Wang and Tuoya Wulan in Beijing

INTRODUCTION

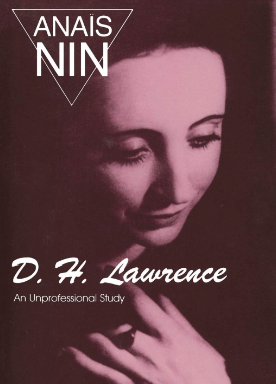

Blake’s talk focused on Anaïs Nin’s intimate portrait – D.H. Lawrence: An Unprofessional Study. Through Nin’s study, diaries, fiction and further writings including The Novel of the Future, he considered Lawrence’s influence on Nin not just as the great emancipator of the unconscious, but with particular attention to the literary impact of Lawrence’s language and style.

BIOGRAPHY

Blake Matich is a writer and editor based in London (but with an itinerancy to rival that of Lawrence). Originally from Australia, his first encounter with Lawrence was probably his bronze plaque on Sydney’s Writer’s Walk at Circular Quay. But his first real introduction was through Twilight in Italy – and he has proceeded by intuition through Lawrence’s life and work ever since. At Freie Universität Berlin he wrote his MA thesis on James Baldwin’s philosophy of love in his fiction, a thesis which greatly benefitted from an understanding of Lawrence’s influence. He has sought to do something similar in this talk about Anaïs Nin.

READING

Anaïs Nin

D.H. Lawrence: An Unprofessional Study (particularly the chapters on Experiences, Woman, Language – Style – Symbolism, In Controversy, Women in Love, Kangaroo)

The Novel of the Future

Henry & June (gives a good taste of the diaries, though any sense of Nin’s diary writing will do)

D.H. Lawrence

Kangaroo

PRESENTATION

Blake started by sharing that his reading of Anaïs Nin’s D.H. Lawrence: An Unprofessional Study was his first encounter with another Lawrencian – one of ecstatic gratitude and passionate appreciation. Nin was the first of a long line of authors on whom Lawrence had a clear deep and lasting influence, beginning for her in 1929 when she noted in her diary that Women in Love was ‘a strange and wonderful book’. This was at the time when Lawrence was very ill; by the time that she had published her brief first article on Lawrence in The Canadian Forum, “The Mystic Sex: A First Look at D.H. Lawrence”, Lawrence had died. This intense period for Nin, described in the posthumous editing of her unpublished diaries, Henry and June, was full of affairs and art as well as an immersion in Lawrence’s works which culminated in her 1932 Unprofessional Study. In 1936 she visited Morocco and testified that Lawrence influenced her reaction to the physical intensity of the streets. Three decades later, in 1968, The Novel of the Future evidences Lawrence’s ongoing influence on her sense of the scope and depth of the novel form, including in her own practice. Blake particularly, however, admired the brevity, inchoate air, and resemblance to its subject of the Unprofessional Study.

Nin thought that Lawrence was classless, instead constituting a class of those who to some degree resembled him. The book exemplifies as well as praising in Lawrence’s emotional knowledge that comes through intuition, and the means of conveying this in drama and fiction. Nin expresses what many of us experience when reading Lawrence – a culture shock at his sensitivity. Moreover, as Harry T. Moore noted in his introduction to Nin’s book, Nin is rare (especially for her period) in discussing the texture of Lawrence’s writing:

Very often, in fact, it is the under-current of rhythm which makes the careless writing. The words almost cease to have meaning; they have a cadence, a flow, and Lawrence gives in to the cadence. That is why there are so many ‘ands’ and enchantments, repetitions like choruses, words that are meant to suggest more than their own determinate, formal significance. [UPS p. 61]

She also likens his writing to sculpture:

Lawrence attempted some very difficult things with writing. For him it was an instrument of unlimited possibilities; he would give it the bulginess of sculpture, the feeling of heavy material fulness: thus the loins of the men and women, the hips and the buttocks. He would give it the nuances of paint: thus his effort to convey shades of colour with words that had never been used for colour. He would give it a rhythm of movement, of dancing: thus his wayward, formless, floating, word-shattering descriptions. He would give it sound, musicality, cadence: thus words sometimes used less for their sense than their sound. It was a daring thing to do. Sometimes he failed. But it was certainly the crevice in the wall, and opened a new world to us.” [UPS, p. 63-64]

Blake went on to observe that The Novel of the Future evidences how defending and explaining Lawrence gave Nin an orientation for her own work. Like Lawrence himself, she fully acknowledged those who had influenced her:

It is not a bad sign for a young writer to choose a model, for if this choice is genuine, it indicates an affinity and helps the young writer to find where he stands. I find young writers today too eager to disclaim any influences, to pay any homage to those who helped them set their course, as if ashamed of their literary parents. I have no desire to claim that as a writer I was born in a cabbage patch. I owe my formative roots to D. H. Lawrence, Marcel Proust, Djuna Barnes, and the novels of Jean Giraudoux and Pierre Jean Jouve. I was influenced by Rimbaud and the surrealists. [The Novel of the Future, Collins 1970, p. 117]

The next part of Blake’s talk focused on the importance to Nin of Kangeroo specifically. She found that novel to contain the quintessence of Lawrence, and approved of his Australian works in general as being relatively unshaped as art:

Lawrence concentrated on the pursuit of an experience with all the slow, intricate, laborious elements of his own nature. He grew within the novel, in a devious way which is the despair of the formalists. What he discovered in the multitudinous byways of his fancies and his intuitions was sometimes unessential, sometimes unique. He was aware of infinite nuances, both of mood and of thought, and carried out their development relentlessly. The result was a fulness and expansiveness which was wearying to readers who had been brought up on direct, condensed, easily digested literature. [UPS, p. 67]

Nin interpreted Kangeroo in term of the tension for the artist between solitude and fame:

‘The debate’, as Huxley put it, ‘between the solitary artist and the man who wanted social responsibilities and contact with the body of mankind. Lawrence, like the hero of his novel, decided against contact. He was by nature not a leader of men, but a prophet, a voice crying in the wilderness – the wilderness of his own isolation. The desert was his place, and yet he felt himself an exile in it.’ [UPS, p. 29]

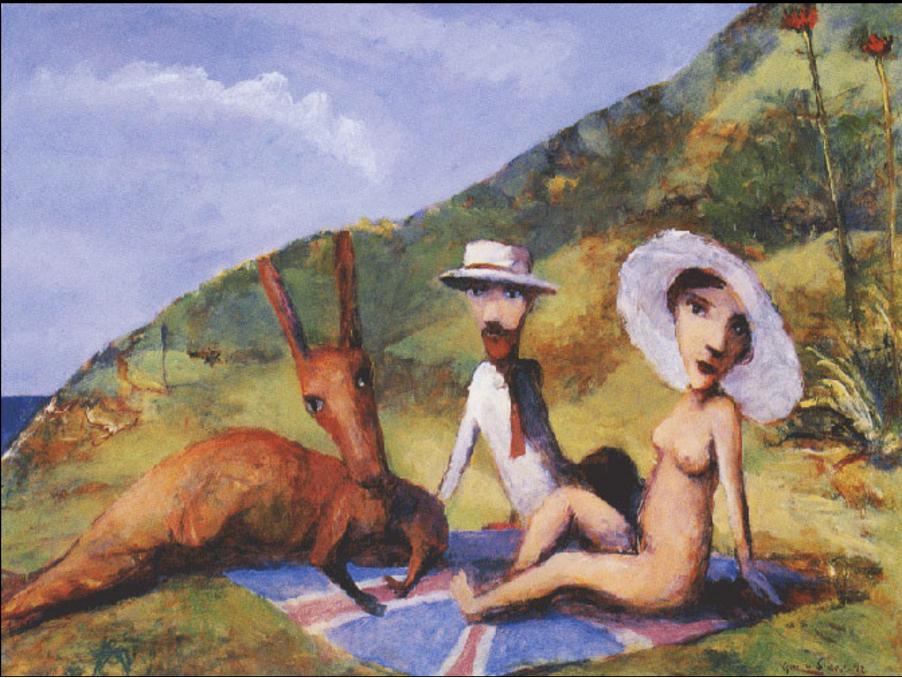

Blake observed that Kangeroo taught Nin how, through instinct and vision, to fictionalise precisely that same part of herself. She also felt vindicated by his ‘androgynous’ writing (she observes that a critic had attributed The White Peacock to a woman). Blake concluded by drawing a parallel between Nin’s response to Kangeroo and that of the Australian artist Garry Shead, who made a series of paintings in response to it:

Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe, by Garry Shead

According to Luke Johnson in this recent article on the painting series:

In Lawrence’s novel, he’d discovered a lens through which to examine this key event from his own life [his shooting of a kangaroo as a boy] and, in Lawrence, a figure onto whom he could overlay his artistic ambitions. The resulting series would be a conglomerate of personal history, biographical research, narrative interpretation and lyrical mysticism, all metaphorised through the world of Lawrence’s mysterious Kangaroo.

Blake ended with an early quote from the Unprofessional Study:

He had a vision. Will it take us one hundred years to understand Lawrence’s vision as it took us one hundred years to understand Blake’s? [UPS, p. 22]

Nonetheless, she presumably and rightly exempted herself from the ‘us’.

DISCUSSION

Jim Phelps thanked Blake for sending him to Nin’s book. Terry Gifford observed that what Nin says about Lawrence’s sound, cadence and rhythm is often overlooked even today, whilst in its own writing the Unprofessional Study reads like ‘sub-Lawrence’. Given how many other responses to Lawrence were being published soon after his death, the distinctiveness of Nin’s response is a remarkable achievement. He also questioned the idea (now an orthodoxy) of Lawrence’s constant shifting of values: he considered Lawrence consistent on many things (including his emphases on flux and intuition), and thought it important to take Lawrence seriously as a thinker, just as Nin does. This is particularly important since we are faced by a number of crises in which values are important. Nin was not concerned with the cosmos in the way that many of us are now; she was principally concerned with relationships; but Lawrence offers important and consistent values and critiques of his own civilisation about which we do need to be articulate. Blake responded that The Novel of the Future is more concerned with today’s issues than is the Unprofessional Study, including in its responses to 1968, and betrayals of the livingness of art. Vic West built on Terry’s point by saying that Lawrence was not opposed to conceptualisation, but to ideas being repeated in a hackneyed way, hence his valuation of a sixth sense in order to keep his apprehension fresh.

Berna Uysal praised Nin’s responsiveness to Lawrence’s ‘pure joy of consciousness’, his ability to use his body as a sponge to soak up experience, and his ability both to name reality and create fiction. Kathleen Vella observed that Nin was both an intimate, intuitive and explanatory critic of Lawrence, and someone who used him to justify her own practice. Helpfully, Nin could see that the characters of Women in Love could be judged as false by realist standards, but that they contain artistic truth. Tina Ferris enjoyed Nin’s theme of itinerancy, as read in relation to Lawrence’s poem ‘Uprooted’. She praised both Lawrence and Nin’s courage of emotional expression. Catherine Brown observed that it was appropriate that this presentation concluded the academic year’s series of presentations to the London Lawrence Group, since it gave historical depth and antecedence to our own passionate appreciations of Lawrence. Blake concluded that Lawrence is currently having a particularly fertile moment as an inspiration to others, and that Nin stood at the beginning of this trend.