Last Saturday evening I went to a talk on the Parthenon Marbles. Aka in less-Greek or less-politically-sensitive circles, those of Elgin.

In the 1880s German immigrants in London built themselves a Turnhalle – a gymnasium – just off Baker Street. About fifteen years ago this barn of a building was acquired by the Hellenic Society of Greek expatriates, and since its main room is now but thinly disguised as an events hall, it was easy, sitting there, to imagine the German immigrants of a century ago pumping their kettlebells and flexing their ironbars. They were not a rich group. The Greeks of London today, by contrast, include some very rich people, and until recently the Hampstead-dwelling former King Constantine II. But on Saturday there were mainly professionals, the evening having been organised by the Society’s medical group; this chimed nicely with the gymnastic setting. Also present was Archbishop Gregorias of Thyateira and Great Britain, to whom I was introduced feeling rather awestruck, since his Eminence not only looks as though he could have walked straight out of a Tolstoy novel, but looks just like Tolstoy in about 1900 (black robes rather than peasant garb aside; this was the time at which Tolstoy was being excommunicated by the Orthodox Church). When he said grace at the beginning of the meal, about half the assembled company were willing and able to join him. Then we had an entirely West European meal, before Spyros Mercouris got up to speak.

Spyros is the brother of the late Melina Mercouri – the 1960s Hollywood film-star-turned-Greek Minister of Culture who led the campaign for the return of the marbles to Greece. Most people have an opinion, more or less strongly-held or well-informed, on this question. Since New College of the Humanities is just a marble’s throw from their current home, this can be seen as a ‘local’ issue for me. I will repeat here a few of the claims made by the talk; counterveiling points can be found elsewhere.

Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, was British Ambassador to Istanbul. The firman (decree) which he obtained from the Sultan, signed by the Haymacam Pasha and addressed to the Governor of Athens, only survives in an Italian translation, which records that Elgin had permission to draw and make models of the Acropolis sculptures without let or hindrance – but not to remove them. He nonetheless managed to remove about a third of them by bribing relevant local people (whilst a third remain in Athens, and a third have been lost). The job was done hastily and messily. The Hellenophile Lord Byron was strongly opposed, and included the following lines in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage:

Dull is the eye that will not weep to see

Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed

By British hands, which it had best behoved

To guard those relics ne’er to be restored.

Curst be the hour when from their isle they roved,

And once again thy hapless bosom gored,

And snatch’d thy shrinking gods to northern climes abhorred!

Elgin kept the marbles in his private collection until he tried to sell them to the British Museum in 1816. A select committee of Trustees questioned him, in accordance with the statutes of the Museum, as to the legality with which they had been obtained, and whether he had taken advantage of his position as British Ambassador in order to obtain them. He had not kept a copy of the firman; yet despite their misgivings, and a heated debate in Parliament, the trustees bought the marbles for £35,000 – about £2,800,000 in 2013 money. Other prominent Britons who have supported their return include Keats, Shelley, and Hardy. Melina Mercouri instigated the building of a new Acropolis museum in Athens to house the Greek marbles, and all of them when they should be reunited. This museum opened four years ago.

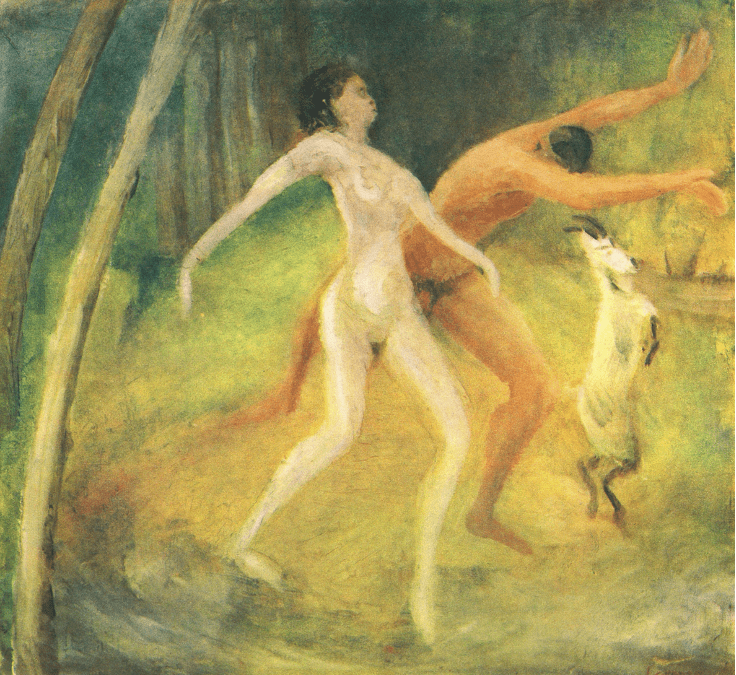

I have no axe to grind on this issue, but I suggest that – especially if you are of the opinion that they should remain where they are, and you live in London – you should make the effort to get to Room 18 of the museum to see them. The marbles show the annual procession of young people to present gifts to the cult statue of Athena, and the battle of the Centaurs and the Greeks. Lord Byron, despite deploring their ‘rape’ (an archaic term for carrying-off, as in the Rape of the Sabine Women), did not admire them, calling them ‘misshapen monuments’ (a phrase which is alas equally applicable to his doggerel on the subject in Childe Harold).

When the talk was over the lights were dimmed and the band took over, playing beautifully haunting music from Ipiros – the far North-West corner of Greece near the Albanian border. The doctors left their tables, joined hands, and started dancing in circles. It was like Natasha’s dance in War and Peace. These Westernised, professional Greek expats, when played Greek music, knew what to do with it. The circle dances of Greece are as old as the Acropolis, and I thought that I learned as much about Greece – ancient and modern – from watching them, than from surveying the poor colourless, mutilated souvenirs of Lord Elgin any day.