Report of the Thirty-Second Meeting of the London D. H. Lawrence Group

Tina Ferris

Windows Imagery in D. H. Lawrence’s Poetry

Thursday 29th February 2024

By Zoom

18.30-20.00 UK time

ATTENDERS

Twenty-four people attended, including, from outside of England, Tina Ferris in Southern California, Shirley Bricout in Vannes, Brittany, Robert Bullock in Paris, Philip Chester in Ottawa Valley, Carlos Augusto in Fortaleza, Brazil, Jim Phelps in Cape Town, David Pratt in Regina, Canada, Shanee Stepakoff in Essex, Connecticut, Kathleen Vella in Malta, and Keith Cushman in North Carolina.

INTRODUCTION

Tina’s talk expanded the second half of her article ‘Message Over the Window Glass: The Window Motif in D. H. Lawrence’s Early Poetry’ [hyperlink]. After briefly looking at four poems, it concentrated on two poems that use window symbolism to highlight emotional storms, before considering three of the early poems from Look! We Have Come Through! in relation to how Lawrence adapted the window motif to his developing relationship with Frieda.

READING

‘From a College Window’ (pre-1908, 1Poems, 7)

‘After School’ (Februrary 1909, 3Poems 1410-11)

‘Dream Confused’ (c. November 1909, 1Poems 8-9)

‘At the Window’ (c. Autumn 1909, 1Poems 67)–This one is the most important of the 4.

‘Elegy’ (Mid 1911-1912, 1Poems, 155)

‘Malade’ (c. February 1910, 1Poems, 76)

‘First Morning’ (May-June 1912, 1Poems, 165)

‘In the Dark’ (July 1912, 1Poems, 170-71)

‘Gloire De Dijon’ (1912, 1Poems, 176)

BIOGRAPHY

Tina Ferris is an independent scholar living in Southern California, DHLSNA Webmaster (2010-2024) and former Lawrence Ranch National Register nomination co-author with Virginia Hyde (1998-2004). Her published articles and book chapters in Lawrence journals and collections include ‘“White Wonderful Demons”: Lawrence and the Heroic Age of Polar Exploration’ in ‘Terra Incognita’: D. H. Lawrence at the Frontiers (2010), ‘D. H. Lawrence and “The Machine Incarnate”: Robots Among the Nettles’ in D. H. Lawrence, Technology, and Modernity (2019), ‘“Surgeon Me Sound/”: Playing Doctor Under the Yew Tree’ (JDHLS 5.3, 2020), and most recently ‘“Message Over the Window Glass”: The Window Motif in D. H. Lawrence’s Early Poetry’ (JDHLS 6.3, 2023).

PRESENTATION

Tina started by describing the third volume of the Complete Poems, published by Cambridge University Press, as a ‘truck of treats’, allowing one to trace poems from their early drafts to their final forms and therefore to understand far more about Lawrence’s technique than had previously been possible. Windows appear over twenty-four times in the early poems, encouraging variously alienation, daydreaming and reminiscence; sometimes the persona is looking in, sometimes out. In ‘From a College Window’ and ‘After School’ Lawrence presents disillusionment with academic life; in ‘Elegy’ and ‘Malade’ he confronts changes beyond his control. In the first he communes with his mother through a window. In the second the sick room is a reflection of his illness, with the window a cave mouth, yet the poem as a whole is anti-Platonic in its embrace of the sick body.

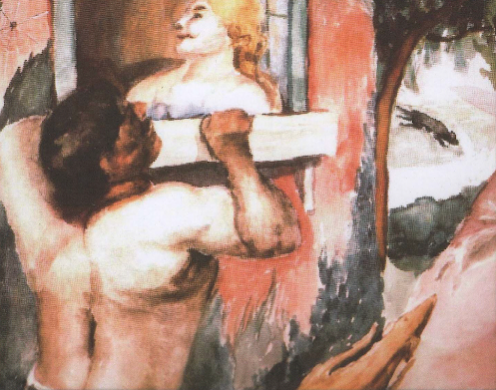

After he met Frieda he developed a new poetic style, and a new kind of window imagery. In several of the poems of Look! We Have Come Through! windows appear in relation to Lawrence’s and Frieda’s conflicts. In ‘First Morning’ a window presents a set of bars that they must break in order to escape their tangled pasts. In ‘Gloire de Dijon’ Lawrence’s painting with words recalls the art of Degas, Monet, Cezanne and Bonnard, who also painted windows (for example Bonnard’s Nude Against the Light of 1908); however, through the window Lawrence and Frieda are finally reconciled. In Lawrence’s own painting, Coal-black Smith of 1928, a blonde inside and a blacksmith outside are both separated and connected by the window. Tina concluded that in Lawrence’s earlier poems (up to and including Look! We Have Come Through!) windows are metaphysical portals into the past or future, but that they lose their significance when Lawrence ‘abandoned himself to living in the quick of time’, after which windows are largely dropped from his poetry.

DISCUSSION

Kathleen Vella noted that Lawrence writes about Cezanne, and that Bonnard appears repeatedly in Woolf’s writings, but she wondered whether there was any direct influence of Bonnard on Lawrence. Tina said she wasn’t sure, but that this was something to explore.

Catherine Brown recalled the moment in George Eliot’s Middlemarch when Dorothea stills the claims of her ego by looking out of her window at struggling humanity beyond; she wondered how often windows play a significant role in Lawrence’s prose. Michael Bell noted that in The Rainbow Tom Brangwen looks through the window at Lydia before he proposes to her; the window, like a picture frame, concentrates his attention in order to allow him emotionally to enter inside, whilst the intimacy is simultaneously aestheticized. Kathleen Vella noted the importance of stained glass both in The Rainbow and ‘A Fragment of Stained Glass’. Shirley Bricout recalled that in Aaron’s Rod Aaron returns home, but stays outside it watching his wife through a window.

Jim Phelps wondered whether Lawrence adequately expressed female desire, given how, for example, ‘Gloire de Dijon’ is focused on male desire. Tina said that she thought that she did, and gave as an example the male-female dialogue in ‘In the Dark’.

Catherine asked Tina to say more about her thesis that Lawrence’s later poems contain less window imagery than the earlier. Tina said that this was supported by her concordance to Lawrence’s poems. In his use of windows imagery he was influenced by older poets, whereas when he dropped it he became a modern poet. Catherine suggested that Lawrence might have had reasons to be opposed to glass – being hard, rectilinear, crystalline and transparent, and Lawrence favouring the soft, mutable, flawed and organic. Tina responded that glass in Lawrence’s time had many imperfections, indeed ‘a funhouse effect’, and might be brown; as a result the light could change as you moved around it, and it did not simply reveal. Victor West wrote later that, even in some of the early poems, the ideal is to block the outside world; thus in ‘The Best of School’ the blinds are drawn, allowing the teacher and boys an ideal unity in concentration. In his late poems, Lawrence yearns for blackness and oblivion, meaning that he again has no interest in looking out. Tina agreed that Lawrence’s renunciation of ‘looking out’ was indeed an important feature of his last poems.