The following article is the pre-edited version of a chapter in Cultures of London: Legacies of Migration edited by Charlotte Grant and Alistair Robinson (London: Bloomsbury, 2024). It is reproduced here with the permission of the editors.

Abstract

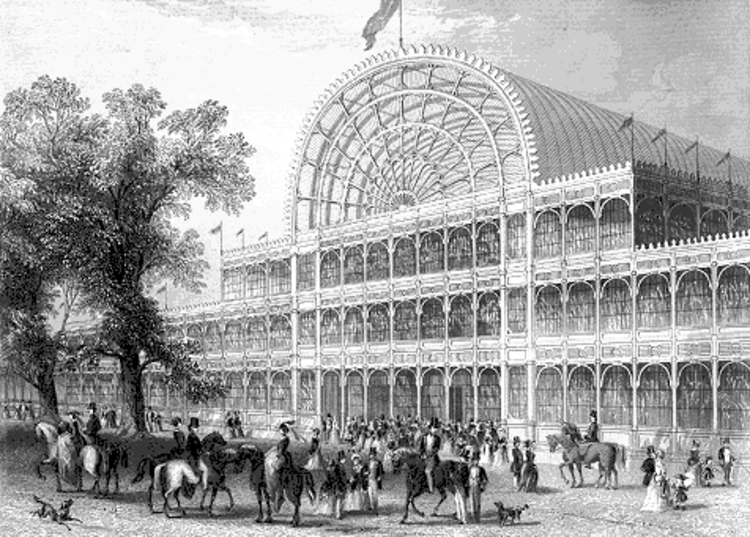

This chapter describes the early 1860s dispute between the radical Russian philosopher Nikolai Chernyshevsky and the anti-radical Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky, as centred on their contrasting responses to the Crystal Palace built for the Great Exhibition in London in 1851. The Palace represented the cutting edge of modernity of the country that itself represented technological and social progress to Westernising Russians. By the same token it represented a sinister totalitarianism to Dostoevsky, who rightly identified in the younger generation of radicals who admired it the seeds of the Revolution that was eventually to come. Both went to London to visit the Russian expatriate philosopher Alexander Herzen, who tried but ultimately failed to keep the more conservative and more revolutionary wings of Russian reformism working together, and whose thoughts about London influenced Dostoevsky’s own. Moreover Dostoevsky’s visit coincided with the 1862 World Exhibition, which horrified him in the same way as the Crystal Palace (by then rebuilt in Sydenham), and which like the Great Exhibition had a cosmopolitan ethos which Slavophiles such as he rejected, and which Britain has arguably since lost.

Introduction

In Russia’s post-revolutionary future – as imagined by the heroine of an 1863 novel by Nikolai Chernyshevsky – the masses would live in crystal palaces. Later that same year one of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s most famous protagonists argued that a crystal palace was no fit dwelling for a free person.

To understand why this intra-Russian dispute between a rationalist materialist feminist revolutionary and an Orthodox peasant-orientated anti-revolutionary Slavophile played out around the image of a building constructed in London twelve years earlier, we need first to revisit the circumstances of its creation. The 1851 Great Exhibition, the world’s first ‘world fair’, showcased 17,000 exhibitors including 384 from Russia.[i] The visitors were similarly international:

in the crowds there were … flags of all peoples … the French Tricolore and the Dutch lion, the British unicorn and Irish harp, the two-headed eagle of Austria, the black eagle of Prussia, and the white eagle of Russia. All these banners, which until now had only been found on the battlefield, are now flying together peacefully in the industrial basilica. Under the arches of this building, people were speaking in every dialect, as in the time of Babel.[ii]

Such was the enthusiastic May 1851 report in Современник (The Contemporary), which reported regularly on the Exhibition. It was particularly enthusiastic about the exhibition’s building, which was ‘so remarkable that we would like to offer some pleasure to our readers by presenting them with a view of its facade, which we await hourly from London.’[iii] The English soubriquet soon coined for Joseph Paxton’s building was as early as May 1851 translated into Russian as кристальная палата (‘crystal chamber’, presumably because ‘palata’ sounds closer to ‘palace’ than the direct translation дворец ‘dvorets’)[iv]; by July The Contemporary was imitating the English version by using initial capitals.[v]

The Contemporary was not the only Russian journal to report on the exhibition, but, given its radicalism, it was unsurprising that its coverage was positive. That journal represented the Westernising trend in Russian society, which looked to Europe as a model to be emulated, and which (especially in the post-Napoleonic anti-French reaction) held England in particular to be the epitome of liberalism, technocracy and modernity. Westernisers were also, as The Contemporary’s coverage suggests, liable to understand the Crystal Palace in similar terms to its English admirers – as a manifestation of enlightenment, healthiness (it was well lit and ventilated), egalitarianism (its transparency contrasted with French autocratic architecture), and celebration of both natural history and industry (the two in combination creating a narrative of evolution).[vi] By such English and Russians as embraced this conception, Russia was by contrast seen as undeveloped and autocratic. The Russian exhibits may have underlined this: chiefly raw materials on the one hand, and such malachite ornaments as were commissioned by the aristocracy on the other.[vii] From this perspective it would have seemed just that the host nation (empire included) gave itself pride of place in the Exhibition, occupying half the display space and taking half the gold medals for best products; Russia was awarded one percent.[viii]

Russian visitors would have been less enthusiastic about the xenophobic fears voiced by many English opponents of the Exhibition, concerned by the large number of foreigners drawn to London by the event, and the fact that they included radicals taking refuge in the wake of the failed 1848 European revolutions.[ix] Nonetheless, radicals had good reason to be drawn to England, which was markedly tolerant of political refugees. Moreover the tensions between the British and Russian governments in the build-up to the Crimean War gave the British a motivation to tolerate Russian dissidents specifically. Thus it was that the agrarian socialist Alexander Herzen came to London the year after the Exhibition, escaping the Second Empire that had just been established in France, and having previously left Russia where he had spent five years in Siberian exile. The following year he opened the Free Russian Press, which produced several Russian-language journals (most famously The Bell) that argued for reforms such as the emancipation of the serfs. His journals evaded tsarist censorship by being smuggled into Russia, where they became widely influential. From that point onwards Herzen’s London home became a focal point for Russian political activists – often visiting him either in order to remonstrate with him from a position of greater radicalism, or from one of greater conservatism.

Chernyshevsky

In June 1859 one such visitor in the former category was the thirty-one-year-old Nikolai Chernyshevsky, a theorist of rationalist utilitarian socialism with Russian characteristics. In July 1854 he had demonstrated his enthusiasm for the Crystal Palace by writing a glowing review (based on others’ accounts) of its reopening in the suburb of Sydenham: ‘everything demonstrates that the new Crystal Palace in Sydenham is something unusually magnificent, elegant, and dazzling’.[x] The reason for his visit to Herzen was that the latter had criticised his generation of radicals for over-reliance on abstractions and an extremism that played into the hands of reactionaries. Both failed to convince the other, and the dispute continued in the pages of The Bell and The Contemporary, of which Chernyshevsky had in 1853 become the editor.[xi]

It is not certain that Chernyshevsky visited the Palace in 1859, but, given his enthusiasm for the building as demonstrated both before and after his London visit, it is highly likely. He returned to a Russia in which pressure was building on Alexander II to emancipate the serfs. After he did so in 1861 the new climate of reform and relaxed censorship encouraged further radicalism, and in St Petersburg in 1862 there were a series of student protests and suspicious fires.[xii] It was in this context that Chernyshevsky was on 7 July (wrongly) arrested for connections to a revolutionary organization, and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress pending his trial.[xiii]

It was there – having convinced his guards to give him pen and paper with the promise that he would only write fiction – that he wrote his only novel and most famous work, What is to be Done? It inverted the depiction of the younger generation of ‘nihilists’ in Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons of earlier that year by positively representing four young radicals. Its heroine, the lower-middle-class Vera Pavlovna, escapes from an oppressive family and sets up successful sewing cooperatives and communes before training as a doctor. Her ideological emancipation is marked and helped by four dreams hosted by a female spirit. In the first she is shown a young woman of fluctuating nationality (‘First she’s English, then French; now she’s German, then Polish; she becomes Russian, English again’) being liberated from ‘a damp, dark cellar’ into a beautiful field. Later the novel’s readers are similarly enjoined to ideologically ‘Come up out of your godforsaken underworld … Come out into the light of day, where life is good’.[xiv]

In the fourth and most famous dream, Vera sees the future. In a rural paradise

‘There stands a building, a large, enormous structure … What style of architecture? There’s nothing at all like it now. No, there is one building that hints at it – the palace at Sydenham: cast iron and crystal, crystal and cast iron’.[xv]‘Crystal palace’ is translated хрустальный дворец, the noun now directly translating ‘palace’, and the adjective хрустальный connoting the heavenly and sublime (in contrast to The Contemporary’s кристальный, which connotes cold, crystalline form). In the building over a thousand people are dining with place settings made of aluminium and crystal. It is a worker’s cooperative where ‘What everyone can afford together is provided free; but a charge is made for any special item or whim’.[xvi] Vera is then shown the Russian far South, where the former desert has been irrigated and covered by ‘enormous buildings stand[ing] three or four versts apart … the same sort of enormous crystal building’. Here the population live during the cold months. Everyone is elegantly dressed; the dining hall (with room for 9,000) is lit by electric light, and sound-proofed rooms lead off it where couples may retire to have sex. Nobody is forced to live communally; those who wish live ‘just as you now live in those Petersburgs, Parises, and Londons of yours’; but ninety-nine percent of the people choose to do so. The guide ends Vera’s dream by enjoining her to ‘Strive toward it [this future], work for it, bring it nearer, transfer into the present as much as you can from it’.[xvii]

The idea of communal living in large buildings was pioneered by the utopian socialist Charles Fourier, an important influence on both Chernyshevsky and Herzen; he called such institutions phalanstères. The journalist Henry Mayhew may have been influenced by his conception in his 1851 novel 1851; or, the Adventures of Mr. and Mrs. Sandboys and Family who came up to London to ‘enjoy themselves,’ and to see the Great Exhibition. The eponymous family is invited to stay in a ‘Monster Lodging House which was to afford accommodation for one thousand persons from the country’ In response Sandboys asks ‘whether it was probable that he, who had passed his whole life in a village … would, in his fifty-fifth year, consent to take up his abode with a thousand people under one roof, with … policemen to watch him all night, and a surgeon to examine him in the morning!’.[xviii] He is, however, focused on getting a ticket to the Crystal Palace, which he sees as a haven of rationality even if one of imperfect accessibility (the tickets initially cost £1; only a month later were they reduced to a shilling on certain days, and that still excluded the poorest).[xix] Chernyshevsky, therefore, combined the vision of a phalanstery with the architecture of the Crystal Palace; universal accessibility with modern luxuries; and the roles of education-provision and pleasure-provision that were less perfectly combined at Sydenham.

What is to be Done?, exfiltrated from prison, was published in The Contemporary in 1863. By this time Chernyshevsky had been tried, put through a mock execution, and sentenced to Siberia for fourteen years’ hard labour and lifelong exile. He wrote little more.[xx]

Dostoevsky

A few months before his arrest Chernyshevsky had been visited by Dostoevsky, himself only three years returned from a decade’s exile in Siberia after his own trial, and mock execution, for seditious activities. But Dostoevsky was now at the beginning of a trajectory towards a more conservative, Slavophile (anti-Westernising) position. He saw Chernyshevsky as dangerously siding with the forces causing disturbances in St Petersburg in 1862, and wished to remonstrate with him. Like Herzen, he failed to change his mind.[xxi]

Not long thereafter, shortly before Chernyshevsky’s arrest, Dostoevsky decided to finally inspect Europe, which had been the object of veneration in the Fourierist circles of his radical 1840s youth. As he parodically put it: ‘After all, literally almost everything we can show which may be called progress, science, art, citizenship, humanity, everything, everything stems from there, from that land of holy miracles. The whole of our life, from earliest childhood, is shaped by the European mould.’[xxii]

So he spent two and a half months of 1862 in Europe, including eight days in London where he visited Herzen at his Paddington home.[xxiii] In the previous year Herzen had been visited by Tolstoy, the revolutionary Bakunin (having escaped Siberian exile by travelling Eastwards round the world), and Turgenev. He and Dostoevsky soon discovered that they were both troubled by Chernyshevsky’s generation of ‘nihilists’, and that they both believed that the future of Russia lay in a system based on the peasant commune (albeit Herzen’s conception was atheist and Dostoevsky’s Orthodox).

It is not known whether Dostoevsky visited the Crystal Palace at Sydenham. But he certainly visited the World Fair which was held between May and November 1862 in a new building (later partially rebuilt as the Alexandra Palace) in South Kensington. This exhibition sought to outdo that of 1851, and the intervening imitative fairs such as Paris 1855, on every criterion – thus enacting the spirit of competition that it praised, and proving its own hypothesis of progress.[xxiv] There were twice the number of exhibitors as in Hyde Park, and the building was much larger; its two domes were the world’s largest made of glass.

Back in Russia Dostoevsky wrote a rumination on his tour, Winter Notes on Summer Impressions, published in 1863. In it he described London in a chapter entitled ‘Baal’, adumbrating the idea that England worshipped a monstrous individualist spirit with complete frankness. Unlike Paris, London was unembarrassed by its extremes of wealth, prostitution and crime; each morning the preceding night’s horrors were forgotten as the day’s capitalist business was embarked on with vigour:[xxv]

The immense town, for ever bustling by night and by day, as vast as an ocean, the screech and howl of machinery … the apparent disorder, which in actual fact is the highest form of bourgeois order, the polluted Thames, the coal-saturated air, the magnificent squares and marks, the town’s terrifying districts, such as Whitechapel with its half-naked, savage and hungry population, the City with its millions and worldwide trade, the Crystal Palace, the World Exhibition’[xxvi]

He uses the term кристальный дворец, using the adjective which connotes crystalline clarity. The two last terms in the paragraph above suggest that he is not conflating them; but his response to both is aligned:

The Exhibition is indeed amazing … you realize the grandeur of the idea … And you feel nervous … Can this, you think, in fact be the final accomplishment of an ideal state of things? Is this the end, by any chance? … You look at those hundreds of thousands, at those millions of people obediently trooping into this place from all parts of the earth … It is a biblical sight, something to do with Babylon, some prophecy out of the Apocalypse being fulfilled before your very eyes. You feel that a rich and ancient tradition of denial and protest is needed in order not to yield … not to bow down in worship of fact, and not to idolize Baal … let us admit I had been carried away by the décor; I may have been. But if you had seen how proud the mighty spirit is which created that colossal décor and how convinced it is of its victory and its triumph, you would have shuddered at its pride, its obstinacy, its blindness.[xxvii]

Three years later, in Crime and Punishment, he would make the connection between London’s poverty and its famous palace by ironically naming a seedy St Petersburg pub Хрустальный дворец (using the more ethereal adjective).[xxviii] These views have much in common with Herzen’s, and it is highly likely that Dostoevsky’s conversations with Herzen coloured his view of a city where he spent only eight days, and could not speak the language.

The narration of Winter Notes on Summer Impressions makes good its stated distrust of totalising systems by being itself frequently facetious, self-critical, and dialogic with the reader. The same is still more true of the fictional narrator of Notes from Underground which Dostoevsky published the following year (1864). The fact that the nameless underground man intentionally inhabits a spiritual underground recalls and inverts the message of What is to be Done?, which is to draw its readers out of their mental cellars, whereas Notes from Underground drags the reader into that of the narrator. The extent to which he is intended to be an unreliable narrator is the subject of intense critical debate. The novel is in two parts; in Part 1 the forty-year-old narrator sets out his anti-rationalist, anti-utilitarian credo; in Part 2 he relates certain masochistic and sadistic incidents from his early twenties which exemplify the life of an ‘underground man’. These appeared in separate instalments, and Part 1 has since been republished in isolation, allowing the narrator the more easily to be presented as a proto-existentialist hero. It seems relevant that the narrator’s brief statement of yearning for Christian faith was edited out by the censor,[xxix] leaving only the hint: ‘I know myself … that it isn’t really the underground that’s better, but something different, altogether different, something that I long for, but I’ll never be able to find!’[xxx] – since such a yearning would both validate his criticisms of Western rationalism, and explain his current incapacity to find redemption from what is, in its intense articulacy and self-consciousness, itself a parodic exaggeration of rationality.[xxxi]

What is clear, however, is that the novel is a deliberate attack on What is to be Done? of the previous year. When the narrator asks: ‘Oh, tell me who was first to announce … that man does nasty things simply because he doesn’t know his own true interest; and that if he were to be enlightened … he would stop doing nasty things at once’ the answer is, as his readers would have known, Chernyshevsky.[xxxii] He continues parodically: ‘new economic relations will be established, all ready-made, also calculated with mathematical precision … Then the crystal palace will be built. … Of course, there’s no way to guarantee … that it won’t be, for instance, terribly boring’.[xxxiii] His critique of Chernyshevsky’s utopianism has a considerable overlap with Aldous Huxley’s Savage’s objections to the Brave New World: ‘Man needs only one thing – his own independent desire, whatever that independence might cost and wherever it might lead’; ‘there is one case, only one, when a man may intentionally, consciously desire even something harmful to himself … namely: in order to have the right to desire something even very stupid and not be bound by an obligation to desire only what’s smart’.[xxxiv] Life in the хрустальный дворец is therefore oppressive: ‘suffering is not permitted in vaudevilles, that I know. It’s also inconceivable in the crystal palace … Yet, I’m convinced that man will never renounce real suffering … perhaps I’m so afraid of this building precisely because it’s made of crystal and it’s indestructible, and because it won’t be possible to stick one’s tongue out even furtively’.[xxxv] The doubly repressed (by the narrator and the censor) Christian sentiment of the novel may also have been offended by the irreverent ecclesiastical aspect of the Crystal Palace, with its nave and transepts, three times the size of St Paul’s, and by the same token vastly bigger and lighter than any Orthodox church. The critique is extended to St Petersburg – by name and design Russia’s most Westernising city, younger than New York – which is described as ‘the most abstract and premeditated city in the whole world’.[xxxvi] In this sense it is still more to be condemned than ‘Baal’.

The Future

In 1870 Herzen died; two years later he was depicted as the inadvertent intellectual father of the nihilists in the character of Verkhovensky in Dostoevsky’s novel The Demons (Verkhovensky is appalled to discover the evolution of his own ideas in a novel called What is to be Done?). Chernyshevsky, meanwhile, was a model for the eponymous demons of the younger generation. That year Chernyshevsky finished his penal servitude, but had another seventeen years of Siberian exile still ahead of him. Two years later the reforming Tsar Alexander II visited the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, implicitly affirming its importance in the Russian imagination. In 1881, the month after Dostoevsky had died, he was assassinated by populists – one step towards the revolution that Dostoevsky’s novels had predicted.

What is to be Done? inspired many revolutionaries through the decades of reaction that followed (Lenin foremost amongst them), and the novel became canonical reading in the Soviet period, when it was far more read than any of Dostoevsky’s works. Vladimir Tatlin’s famous 1919-20 crystalline design for the tower of the Third International was arguably the Soviet version of the Crystal Palace. But it was never built, and by the time that the Sydenham palace had burned down in 1936 Soviet architecture had moved away from sheet glass and towards the Stalinist baroque, arguably in reflection of Bolshevism’s departures from its founding idealism. Back in London the Millennium Dome beat the reconstruction of the Crystal Palace as a proposal to celebrate the millennium, presumably due to a rejection of the latter’s associations with Empire, and a desire to be similarly forward-looking. Indeed, the Millennium Dome was its modern British equivalent: like its forebear gigantic, panoptical, nationally self-celebratory, and self-consciously progressive – yet with scant celebration of cosmopolitanism, and nothing like the same effect on the world. The fact that the Dome has had a fraction of the Crystal Palace’s international attention, let alone its impact on international political debate (a latter-day Dostoevsky would dislike the Dome’s ethos, but is unlikely ever to have heard of it), fits with Britain’s reduced status, openness, and appeal, to the world.

Acknowledgment

I would like to acknowledge the support and advice given to me in researching this chapter by Sean Mitchell, a London Blue Badge Guide specialising in the history of Russian expatriates in London.

Bibliography

Chernyshevsky, Nikolai. What is to be Done? 1863. Translated by Michael R. Katz.

Introduction by Miachael R Katz and William G. Wagner. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1989.

- Что делать?

https://royallib.com/read/chernishevskiy_nikolay/chto_delat.html#0

http://www.lib.ru/LITRA/CHERNYSHEWSKIJ/chto_delat.txt

Dostoevsky, Fyodor. Crime and Punishment. 1866. Translated by David McDuff.

London: Penguin, 2003.

- Преступление и наказание.

https://ilibrary.ru/text/69/index.html

— Notes from Underground. 1864. 4th edn. Translated by Michael

- Katz. New York: Norton, 2001.

- Записки изъ подполья.

https://royallib.com/read/dostoevskiy_fedor/zapiski_iz_podpolya.html#0

- Winter Notes on Summer Impressions. 1863. Translated and

introduced by Kyril FitzLyon. Richmond: Alma Books, 2016.

- Зимние заметки о летних впечатлениях

https://royallib.com/read/dostoevskiy_fedor/zimnie_zametki_o_letnih_vpechatleniyah.html#0

Frank, Joseph. Dostoevsky: The Stir of Liberation, 1860-1865. Princeton, New

Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Jackson, Robert Louis. The Art of Dostoevsky: Deliriums and Nocturnes. Princeton,

New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1981.

Katz, Michael R. ‘“But This Building: What on Earth Is It?”’. New England Review

vol. 23, no. 1 (2002): 65–76.

Kelly, Aileen M. The Discovery of Chance: The Life and Thought of Alexander

Herzen. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Landon, Philip. ‘Great exhibitions: Representations of the Crystal Palace in Mayhew,

Dickens, and Dostoevsky’. Nineteenth-Century Contexts, 20:1 (1997): 27-59.

Mayhew, Henry and George Cruikshank. 1851; or, the Adventures of Mr. and Mrs.

Sandboys and Family who came up to London to ‘enjoy themselves,’ and to see the Great Exhibition. London: David Bogue, 1851.

Salvesen, Britt. ‘“The Most Magnificent, Useful, and Interesting Souvenir”:

Representations of the International Exhibition of 1862’, Visual Resources, 13:1 (1997): 1-32.

Young, Sarah J. Blog posts on the website site ‘Russian Literature, History and

Culture’:

[i] https://sarahjyoung.com/site/2011/07/28/russian-perspectives-on-the-great-exhibition-6/

The four blog posts by Sarah J. Young referenced in this article are based around transcriptions, and Young’s own translations, of articles about the Great Exhibition published in The Contemporary.

[ii] https://sarahjyoung.com/site/2011/05/29/the-opening-of-the-great-exhibition-a-view-from-russia/

[iii] https://sarahjyoung.com/site/2011/07/28/russian-perspectives-on-the-great-exhibition-6/

[iv] https://sarahjyoung.com/site/2011/05/29/the-opening-of-the-great-exhibition-a-view-from-russia/

[v] https://sarahjyoung.com/site/2011/06/09/russian-perspectives-on-the-great-exhibition-2/

[vi] Landon, Philip, ‘Great exhibitions: Representations of the Crystal Palace in Mayhew, Dickens, and Dostoevsky’, Nineteenth-Century Contexts, 20:1 (1997): 27-59 (27-31).

[vii] https://sarahjyoung.com/site/2011/07/15/chaucer-chernyshevsky-crystal-palace/

[viii] Landon, ‘Great exhibitions’, 29.

[ix] Ibid, 28.

[x] Katz, Michael R, ‘“But This Building: What on Earth Is It?”’, New England Review

vol. 23, no. 1 (2002): 65–76 (69).

[xi] Kelly, Aileen M, The Discovery of Chance: The Life and Thought of Alexander

Herzen (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2016), 486.

[xii] Michael R Katz and William G. Wagner, ‘Introduction’ to Nikolai Chernyshevsky, What is to be Done?, 1863, translated by Michael R. Katz (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1989), 6-7.

[xiii] Katz and Wagner, ‘Introduction’, 14.

[xiv] Chernyshevsky, What is to be Done?, 129-30, 313.

[xv] Ibid, 370.

[xvi] Ibid, 371-2.

[xvii] Ibid, 375-78, 379.

[xviii] Mayhew, Henry and George Cruikshank, 1851; or, the Adventures of Mr. and Mrs.

Sandboys and Family who came up to London to ‘enjoy themselves,’ and to see the Great Exhibition (London: David Bogue, 1851), 17.

[xix] Landon, ‘Great exhibitions’, 49.

[xx] Katz and Wagner, ‘Introduction’, 14.

[xxi] Frank, Joseph, Dostoevsky: The Stir of Liberation, 1860-1865 (Princeton, New

Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986), 151.

[xxii] Fyodor Dostoevsky, Winter Notes on Summer Impressions (1863), translated and

introduced by Kyril FitzLyon (Richmond: Alma Books, 2016), 13.

[xxiii] Dostoevsky, Winter Notes, 3, 9; Frank, Dostoevsky, 188.

[xxiv] Salvesen, Britt, ‘“The Most Magnificent, Useful, and Interesting Souvenir”:

Representations of the International Exhibition of 1862’, Visual Resources, 13:1 (1997): 1-32 (1-2).

[xxv] Dostoevsky, Winter Notes, 48-49, 58.

[xxvi] Ibid, 49-50.

[xxvii] Ibid, 50-51.

[xxviii] Fyodor Dostoevsky, Crime and Punishment (1866), translated by David McDuff

(London: Penguin, 2003), 191.

[xxix] Fyodor Dostoevsky, Notes from Underground (1864), 4th edn., translated by Michael

- Katz (New York: Norton, 2001), 95-96.

[xxx] Ibid, 27

[xxxi] Robert Louis Jackson makes this argument in The Art of Dostoevsky: Deliriums and Nocturnes (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1981), 161.

[xxxii] Dostoevsky, Notes from Underground, 15.

[xxxiii] Ibid, 18.

[xxxiv] Ibid, 19, 21.

[xxxv] Ibid, 25.

[xxxvi] Ibid, 5.