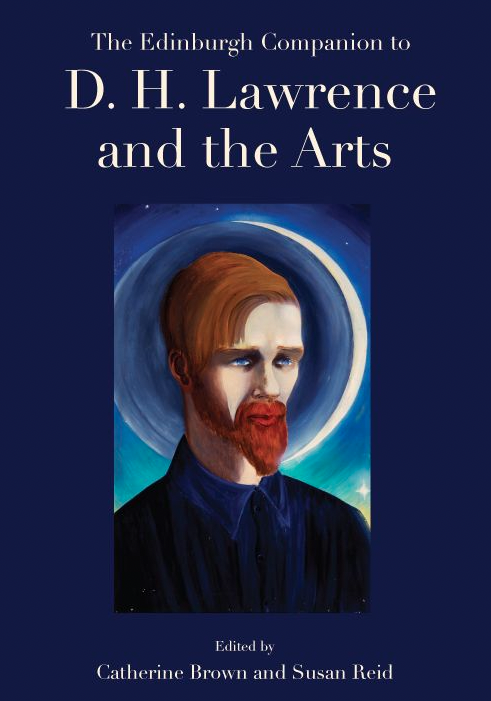

Dorothy Brett, D. H. Lawrence with Halo, 1925

The following is the pre-edited version of the Introduction to The Edinburgh Companion to D. H. Lawrence and the Arts (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020) which I co-edited with Susan Reid. Please find elsewhere on this site my own chapter within the volume, ‘D. H. Lawrence: Icon’.

This Introduction was written jointly by Susan Reid (editor of Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies) and myself. It is reproduced here by kind permission of Susan Reid and Edinburgh University Press.

INTRODUCTION

‘It is Art which opens to us the silences, the primordial silences which hold the secret of things’ (STH 140). So Lawrence said in his first public statement on aesthetics, the paper ‘Art and the Individual’ delivered to the Eastwood ‘Debating Society’ in 1908. This assertion, which immediately follows an extract of poetry, places verbal art in the context of all art, of which the role is to escape the conscious and the verbal. Admittedly, most of his prodigious output, from a life cut short at the age of forty-four in 1930, was in written form: not just the long and short fiction for which he is best known, but poems, plays, travel writing, literary criticism, art criticism, social criticism, historiography, philosophyphysiological psychology and 6000 extant letters. Yet the letters, like much of his prose, carry a sustained dialogue about the arts – often with other artists – that frequently interprets painting, sculpture, architecture, design, clothing, music, dance and cinema in relation to the verbal arts, history, philosophy and politics. Lawrence lived at a time of unprecedented experimentation across and between the arts, much of which he experienced through his growing artistic network, and in which he himself engaged. Before he embarked on a literary career, he painted, sang hymns that inspired his lifelong wonder of words and other worlds, and organised impromptu dramas and sing-songs – pursuits which came to fruition in his final years in his own paintings and his operatic play David, for which he composed music for ten songs.

What it means to consider Lawrence as a practitioner of many and overlapping arts is one over-arching aim of this Companion, which also revisits his perceived distrust of the idea of ‘art’ that has perpetuated his status as an outsider to literary modernism. The other main aim is to make the strongest possible case for his ongoing aesthetic power, and his relevance to a world experiencing several of the problems of his own time in intensified forms. The reassessment starts by concentrating on aesthetic categories which transcend particular art forms. The fact that Part 1, ‘Aesthetics’, constitutes nearly half of the volume fits with an artist who worked in such a wide range of overlapping forms and genres. ‘The Idea of the Aesthetic’, as Michael Bell puts it in the opening Chapter, needs careful orientation in relation to a man whose ‘emphatic valuing of life over art has gained him the still lingering reputation of being anti-aesthetic’. All the contributors in this Part find that his aesthetic attitudes point, as Hugh Stevens argues, ‘in several directions’, and so demand reevaluation of existing critical positions.

Part II, ‘Aesthetic Forms’, concerns Lawrence’s practice of and reflections on a range of artistic forms, considered in three inter-related groups. The first section addresses the ‘Verbal Arts’ of the novel, poetry and his important practice of revising and rewriting, all of which resonate throughout this Companion. The second draws out the fundamental import of the ‘Performance Arts’ in Lawrence’s oeuvre, John Worthen finding that his genius for performance was displaced into his fiction because ‘it was the only place he could thoroughly stage his imaginings’, a view reinforced by Jeremy Tambling’s rereading of the under-valued plays. This focus on performance arts also embraces his wide-ranging engagements with music and dance, and complements Part I’s discussions about the aesthetics of inter-arts modernism and the performance of gender. The third section’s consideration of the ‘Visual Arts’ opens with his ‘painterly criticism’, as Jeff Wallace describes it, and moves to a wider interest in design that he brought to the dust jackets of his books, before addressing his interests in other arts that have been relatively neglected by his critics: sculpture, architecture and clothing. These indicate rich seams for future exploration, as research areas along with dance that have yet to receive the book-length treatment they clearly merit.

Artists have been abundantly responsive to Lawrence’s life and work in a range of media. Part III, ‘Lawrence in Others’ Art’, therefore responds to his works and image as reflected in the art of others up to the present day: in biofiction, film, music and portraiture which can verge on iconisation (or, alternatively, iconoclasm). Beginning with Aldous Huxley, whose Introduction to the first edition of Lawrence’s letters in 1932 insisted that we approach him as an artist, Lee M. Jenkins traces the longevity of biofictional writings about Lawrence originating in ‘the inter-arts aesthetic of 1910s modernism’ through to a contemporary boom. Versions of ‘Lawrence’ survive in biofiction, she argues, ‘as a signifier of the inseparability of life and art’. Louis K. Greiff notes that ‘Seventy-one films devoted to a single author is, by any standard, a remarkable number’, which reflects the ability of his texts to ‘blossom into vivid and compelling scenes reminiscent of recent cinema at its very best’. Similarly Bethan Jones explores examples drawn from more than fifty musical settings of texts by Lawrence that indicate how the soundscapes of selected poems make them especially suitable for setting by composers. Interdisciplinary approaches such as these, as throughout the volume, draw on emerging areas of study to create a more composite understanding of Lawrence. Above all the ‘new modernist studies’ are challenging what it means to be modernist, considering profound engagements with the conditions of modernity, and opening up the concept beyond the remit of superficial morphological innovation.

Lawrence has long been perceived as only questionably a modernist. Sons and Lovers has proved one of his most popular works, whilst The Lost Girl was the only one of his works to win a literary prize in his lifetime (the James Tait Black Memorial). Both are for the most part realist. Holly A. Laird notes that ‘Lawrence is missing from Lawrence Rainey’s prominent Modernism: An Anthology (2015)’, and that he is ‘barely mentioned in the Cambridge Companion to Modernist Poetry (2007)’, so that ‘Lawrence remains even today a maverick within the canon of modernist poetry’. Certainly, the respects in which he is modernist are less striking than are those of the mature James Joyce or Virginia Woolf. Novels such as The Rainbow and Women in Love can mislead the reader into perceiving a realist text and judging it (unfavourably) by realist standards; in fact, as Keith Cushman observes, The Rainbow functions with the ‘allotropic states’ of a different type of ‘ego’ than had existed previously in British characterisation (2L 183). Vincent Sherry extends Lawrence’s analogy to observe that these two novels, originally a single book-project, seem to be ‘made out of each other’s imaginative antimatter’, encapsulating the numerous oppositions within his work and his ongoing experimentation with character and form.

Recent understandings of the umbrella term ‘modernism’ have, as Sarah Edwards notes, broadened in such a way as to more comfortably cover Lawrence’s expansive oeuvre. Moreover recent biographical research (Laird observes) has revealed the extent to which he was well-connected in modernist circles from the very beginning of his career, and increasingly critics are noticing how Lawrence’s aesthetic interests overlapped with those of his contemporaries. He has been called ‘arguably the most Biblical writer of the twentieth century’, but, Shirley Bricout points out, Joyce or Eliot would be close contenders. Lawrence’s engagement with Biblical aesthetics was ‘distinctively intimate’, she notes, and while this description rings true of all his diverse engagements across the arts, this Companion also emphasises common ground with his modernist contemporaries. Like Joyce and Eliot, he wrote about music hall, combining putatively ‘high’ and ‘low’ forms in his novels The Lost Girl and Mr Noon, and was at least as interested in both music and dance as his literary contemporaries. The importance to Lawrence of the Ballets Russes, European Expressionist dance and ‘new physical health practices and martial arts’, as described by Susan Jones, overlaps more broadly with his interests in music and in combining the arts as Wagner and his Expressionist successors sought to do.

The parallels that emerge with other practitioners across the visual arts of modernism are especially striking. Wallace reaffirms Anne ‘Fernihough’s argument that Lawrence had far more in common with the aesthetics of Clive Bell and Roger Fry, particularly through their shared endorsement of the significance of Cézanne, than has been assumed’, whilst Jonathan Long emphasises his collaborations with contemporary artists such as Dorothy Brett on his book jackets. Through Mark Gertler and Ezra Pound, Lawrence was indirectly connected with Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska; his interest in their practice shows clearly in his writing about avant-garde sculpture, as Jane Costin argues. His attention to the built environment was such, Edwards comments, that he helped to shape ‘interdisciplinary debates in architecture, the arts and literature, and in the changing definitions of these terms in the twentieth century’.

Bell asserts that Lawrence shared with those writers now most commonly considered as ‘high’ modernist ‘an ambitious conception of literature as a means of personal and social understanding’ that they inherited from European Romanticism, alongside a perception that Romanticism had ‘run to seed’ in escapist sentimentality ‘over the nineteenth century’. However, he diverged from some of his fellow modernists in equally distrusting the overreaction against emotionality that characterised their neo-classicism and ‘emotional avoidance’: ‘He therefore kept faith with the Romantic tradition’ and disparaged ‘modernist irony’ as ‘a way of handling the emotions with self-protective tongs’. He also diverged from their conception of impersonality: ‘Eliot and Joyce emphasise the impersonality of the artist vis-à-vis the artistic material whereas Lawrence was concerned with impersonality as a quality of feeling as such’.

Sherry extends Bell’s discussion of Romanticism by presenting The Rainbow as embracing the ‘revolutionary possibilities’ of a Romanticism that, rather than being focused on formal political change, emphasises personal and erotic liberation at the level of the individual: thus Ursula in The Rainbow achieves a type of autonomy which her grandmother Lydia, when she was oppressed in her marriage to a Polish revolutionary, did not. However, the First World War’s assault on Lawrence’s belief in the revolutionary potential in English society rendered Women in Love overwhelmingly pessimistic and suffused with the Decadence into which a thwarted Romanticism degenerated: Hermione is ‘a figure out of Decadence central casting’ who holds Birkin back, and even in the Alps – transcendent refuge of the Romantic spirit – Loerke represents what David Trotter describes as ‘Lawrence’s best shot at a degenerate’. These decadent and degenerate figures in Women in Love also contribute to a critique of Wagner’s idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, which, Susan Reid argues, was a common modernist concern rooted in a decaying ‘Romantic ideal of unifying the arts as a means of restoring wholeness in society’.

Lawrence’s strong engagements with the aesthetic debates and trends of his time are stressed in number of Chapters which treat Lawrence as a ‘practitioner critic’ – that is, an artist who writes criticism and a critic who produces art. The breadth of art to which he responded is reflected in the variety of his own output, as Laird perceives in relation to his poetry: ‘So dissimilar are the kinds of verse to which Lawrence responded that his general openness … helps account not only for this maverick status, but for the sheer variety of verse forms practiced in his poetry’. So diverse are these influences that some are yet to be fully explored, not least his shared modernist roots in PreRaphaelite and Decadent poetry. Cushman frames Lawrence’s ‘Idea of the Novel’ in the light of his 1925 essays on the novel, which crystallise his disagreement with those writers who elevate art above life (from Flaubert to Joyce, Proust and Richardson), and reinforce his own emphasis on ‘quickness’ of being.

He was also a confident critic of paintings from an early age, Wallace comments, ‘such that, when he takes his own place in the world of art, a critical disposition is already well primed’. Moreover he ‘could not have persevered with his technically maladroit painting without the theoretical conviction that the painterly effect of the vital could be achieved outside of formal technique and training’. He repeatedly used existing art as something to react away from, which is why his early enthusiasm for other artists was often eventually inverted, mirroring what Laird describes as ‘The well-known pattern of his personal relationships, of sympathy followed by judgement’. Bell puts it thus: ‘As a creative writer he was necessarily a creative reader always honing his own artistic commitments against the whetstone of other writers’.

Lawrence’s criticism is frequently inter-artistic: Cushman notes that ‘Lawrence begins “Art and Morality” with a discussion of a Cézanne still-life’ and Wallace that Study of Thomas Hardy is in part art-historical. The same is true of his art itself. In the field of historiography, Andrew Harrison relates his treatment of historical events and processes ‘to his interest in (and production of) other historiographical forms such as autobiography, biography, fictional biography, and the various hybrid historical fictions now discussed under the term “auto/biografiction”’. Reid explores Lawrence’s attraction to concepts of the Gesamtkunstwerk throughout his writings, including The Plumed Serpent, an operatic novel which combines ‘travelogue, fiction and gospel’ with poetry, music and dance; to this list Judith Ruderman adds that it also ‘offers perhaps the most vivid examples of fabric design and the clothing made from it as applied arts’. Lawrence’s presentations of non-verbal art forms such as dance and music ‒ whether in those forms themselves, or through his writings – frequently point to the limitations of language. As Reid puts it in her Chapter on ‘Music’, works such as ‘The White Peacock, The Rainbow, The Lost Girl, Mr Noon, Aaron’s Rod and David suggest textual experimentation beyond the sound of words to the non-representational potential of music to evoke states of embodied being’.

‘Embodied being’ is never fixed, because the body is constantly in flux. The idea therefore recurs through this Companion that Lawrence – contrary to his depiction by numerous of his detractors and admirers – is an artist whose individual works, and oeuvre, resist any attempt to pin them to a stable ideology. The result of his fluctuating engagements with the moments of life as they pass is what Laird calls a ‘dialectical or conflictual relationalism’: ‘As a person, a poet and a critic, he was inclined to shift perspectives, sometimes abruptly’. Sherry notes that he was ‘protean’: ‘No sooner does he master a literary style than he leaves it behind’. Bell observes that he was aware of this:

‘in the flaming intensity of his life, which he always expected to be short, his intensities would just as quickly be burned out, which he also knew. Accordingly, his most subjective moods and dogmatisms were accompanied by self-deprecating humour; an irony … directed towards himself rather than the object.’

He knows that later ‘other moods’ would ‘supervene to relativise their emotional state which is retrospectively critiqued without losing its subjective authenticity’. Bell’s reading stresses the extent to which ‘Lawrence’s art arises from an exploratory struggle which is an integral part of its meaning’, in contrast to understandings of art works as ‘gem-like’ (1Poems 645). Accordingly, for his readers, ‘fetishising the “work” as noun may frustrate its possibilities as verb’, since his works do ‘not just seek to contain, or record, but to be this process’ of exploration – hence the frequency of open endings to his narratives, and ‘his practice of writing successive versions of the same narrative’.

This last phenomenon is described in detail by Paul Eggert, who enjoins us to understand Lawrence’s works not as finished, but cut off in their development by the necessity to make money from publication:

‘The surprisingly provisional nature of his usually forcefully-expressed ideas comes into focus when we do this; and accepted practices of interpretation, based on the published forms of his writings taken as individual objects, as separate works, become problematic. An unfamiliar Lawrence emerges.’

Eggert argues that this pertains to Lawrence more than most writers, precisely for the reason that Bell describes: his works are exploratory. It follows, Eggert points out, that we should guard against thinking about Lawrence’s revisionary process as ‘benignly evolutionary, in a state of gradual perfecting whose endpoint was always in view from the start’. To complicate the matter further, at any given moment he typically had multiple works in progress, which influenced each other: ‘Taking a break from one to write the other became habitual – and understandable given the extended period that, say, a novel might take to bring to completion. Each work became an element in the fertile soil from which the others sprang’.

It is in these contexts that Reid’s observation that Lawrence resisted the potentially-totalising implications of the Gesamtkunstwerk should be understood. He resisted the integration of individual art forms, or people, into stable wholes, wishing to retain instead ‘the trembling instability of the balance’ between autonomous entities (STH 172). Characters such as Birkin and Ursula in Women in Love and Kate in The Plumed Serpent resist totalising ideologies, whilst Harrison comments that in his ‘Memoir of Maurice Magnus’, ‘Lawrence balances sympathy with critical awareness in a manner which … stresses the strangeness of experience and the provisional nature of our attempts to comprehend it’. In this light many commonplaces about Lawrence’s thought are revealed to be inadequate. Trotter’s Chapter argues that in ‘his writing “life” can on occasion be seen to “flow” more freely under technology’s spell than it would otherwise have done’, and that critics have therefore been wrong to have ‘on the whole take[n] Lawrence at his word’ ‘where technology is concerned’. One formal outcome of Lawrence’s embrace of provisionality has been, as Reid argues, a progressive loosening of form from Women in Love to the ‘fragments’ of Pansies.

Paradoxically, Lawrence’s provisionality is reflected in the one reasonably stable dogma in his writings – the denunciation of the absolute. Cushman identifies as a common theme in all five of his 1925 essays on the novel ‘the rejection of all absolutes’. For example in ‘Morality and the Novel’ Lawrence describes the novel as ‘the highest complex of subtle interrelatedness that man has discovered. Everything is true in its own time, place, circumstance, and untrue outside its own place, time, circumstance’ (STH 172); ‘If you try to nail anything down, in the novel, either it kills the novel, or the novel gets up and walks away with the nail. Morality in the novel is the trembling instability of the balance’. The intrinsic ‘instability of the balance’ in Lawrence’s writings may be seen in the divergent interpretations that his individual works have produced, including in new art works inspired by them. Greiff notes the multiple, strongly-differing films versions that exist of ‘The Rocking Horse Winner’, whilst Bethan Jones describes various approaches to song settings of his overtly-musical poem ‘Piano’. It is true to Lawrence’s protean nature that very various representations of him are found in the biofictions described by Jenkins.

The provisionality of his positions and perceptions correlated with a striking openness to what was culturally foreign to him. Stefania Michelucci distinguishes his texts’ inclusions of foreign languages from the self-conscious, ‘elitist’ ‘intertextuality’ of his fellow modernists, reflecting ‘his need for a closer contact with and a deeper understanding of the peoples and cultures he encountered during his wanderings’. Several of the contributors describe Lawrence’s ‘Primitivism’ in terms not of the unthinking projection of imagined solutions to industrialised countries’ problems onto other countries’ peoples – but of a genuine desire to learn from those who (in Peter Childs’s words) he ‘perceived not to be caught in the civilisational snares with which he was familiar’. Julianne Newmark argues that Lawrence was ‘actively transformed by the aesthetic experience’ of ‘traditional’ aesthetic activities such as the Italian woman’s spinning (described in ‘The Spinner and the Monks’) and Native American dancing (described in ‘The Hopi Snake Dance’). In the same spirit Susan Jones perceives that in Quetzalcoatl and The Plumed Serpent ‘dance played a fundamental role in conveying how the West might need to surrender to a “new way” of life to survive’. Harrison finds that in Lawrence’s text-book Movements in European History his ‘most engaging imaginative passages … concern peoples who had typically been traduced or marginalised in earlier historical accounts – notably the ‘“Germanic races”’ (44); ‘The same desire is felt in the posthumously published Sketches of Etruscan Places, which Lawrence wrote in a spirit of opposition to the scholarly accounts of Etruscan civilisation provided by historians such as Theodor Mommsen’. Even in his reading of the Book of Revelation, Bricout notes, he excavates what he perceives as the suppressed voice of pagan inspiration buried under a strident Christianity.

This openness of sympathy to marginalised groups is just one of several respects in which this Companion presents Lawrence as progressive. As noted above, Sherry stresses the revolutionary potential implied in The Rainbow; Howard J. Booth concurs in noting that Lawrence’s stress on ‘how change can begin at the level of the individual or with close relationships … is the major reason why the final version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover remains a political novel’. In his revisionary Chapter on Lawrence’s ‘Politics and Art’, he argues that this subject ‘can be worked anew if we move away from discussions that redeploy conventional political labels, Rananim and leadership, and pursue instead his exploration of utopian longing’. Indeed, he identifies in Lawrence a strongly ‘utopian trajectory’, particularly in his writings of the 1920s, which owes much to the ‘late Victorian radicalism’ to which he was exposed by the Eastwood radical Willie Hopkin. Booth stresses that the so-called ‘leadership novels’, being exploratory, do not actually support strong leadership, and that Lawrence consistently opposed bullying, whether of the left or the right. He had an accurate sense of foreboding about sinister developments in Germany as early as 1924, as his ‘Letter from Germany’ demonstrates (MM 149-52).

Booth further observes that, though many left-wing critics have accused Lawrence of class treachery, he reengaged sympathetically with his native working class ‘immediately after the First World War and again during the 1926 miners’ strike’. If he critiqued many of the solutions proposed by the left, he also ‘shared much of their critique’; in a similar spirit, Wallace stresses the deliberate claim that Lawrence laid, as a working-class boy, to sight and criticism of the world’s great art. Both Booth and Gemma Moss trace how Lawrence anticipated the thought of the Frankfurt School theorists. Like Adorno, according to Booth, he bemoaned people’s loss of ‘the capability to imagine the totality as something that could be completely different’. Like both Adorno and Benjamin, he critiqued ‘notions of progress and machine-like human activity that have become second nature’, and like Adorno he saw ‘popular culture’ as ‘forming and damaging mind, body and sexual life’. Moss explores further Lawrence’s ‘longstanding opposition to a broad, unspecified notion of popular culture’ – particularly in ‘Pornography and Obscenity’ – whilst arguing that ‘Lawrence moves closer to Frankfurt School theories about how to resist ideology in St. Mawr’. Similarly, Reid identifies an overlap between the different kinds of music auditors described in Aaron’s Rod and Adorno’s sociological typology of listeners in his essay ‘Types of Musical Conduct’.

Lawrence also, however, anticipated more recent movements than the Frankfurt School. What Stevens terms Lawrence’s ‘queer aesthetics’ are sharply relevant at a time when binary concepts of gender and sexuality are being questioned as never before. Stevens argues not only that Lawrence had a ‘persistent fascination with same-sex desire’, but that ‘Rather than dividing human beings into two discrete populations of “homosexuals” and “heterosexuals”, he “queers” the binary between homosexuality and heterosexuality by suggesting that individuals feel desire and love for both sexes’. Even though Lawrence ‘The metaphysician believes that men should not have sex with men’, ‘the aesthetician and the artist celebrates the spectacle of naked men touching … Lawrence’s queer aesthetics have their own truth, and express the beauty of what is prohibited’. His representations of gender fluidity are also touched on by Ruderman, who argues that Lawrence’s interest in clothing and jewellery made him a ‘rare bird’ among ‘male modernist authors’, and men in general.

Lawrence speaks still more loudly to modern ecological concerns. Booth rightly observes that Lawrence’s critique of industrialism made him ‘forward looking’, and not right wing, as Eagleton thought of ‘those who do not accept a modernising industrial world’ (an idea ‘that feels badly dated in our time of environmental crisis’). Bricout writes of ‘his belief in an aesthetic epiphany that enables man to re-establish harmonious relations with the cosmos’. Lawrence’s sense of life on earth as inter-connected, and his holistic concern with ‘all’ that exists in the universe (sometimes punningly personified by him in the god ‘Pan’, Catherine Brown notes) not only fit with, but may guide, modern thought. Brown concludes by arguing that Lawrence’s iconisation as a life-guide, which has pertained to much of his reception history, persists in new forms still – and with good reason.