The following is the pre-edited version of my chapter in The Edinburgh Companion to D. H. Lawrence and the Arts (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020) which I co-edited with Susan Reid. It is reproduced here by kind permission of Edinburgh University Press. Please find elsewhere on this site the editors’ Introduction to this volume.

Introduction: Deification

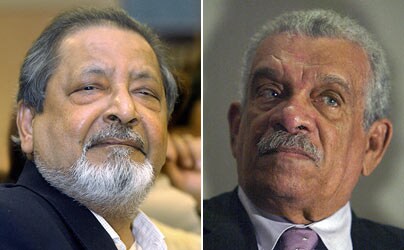

In or around January 1926 Dorothy Brett painted a double portrait of Lawrence as Pan and Christ.

Dorothy Brett, D.H. Lawrence as Christ and Pan, 1926/1963

‘The picture is of a crucifixion. The pale yellow Christ hangs on the Cross, against an orange sunset. With that final spurt of strength before death, he is staring at the vision of the figure in front of him. His eyes are visionary, his figure tense and aware. Before him, straddled across a rock, half-curious, half-smiling, is the figure of Pan, holding up a bunch of grapes to the dying Christ: a dark, reddish-gold figure with horns and hoofs. The heads of Pan and of Christ are both your head. Behind lies the sea.’ (Brett 1933: 275)

The painting reproduced above, however, is not the one.

‘Alas, that the laughter and criticism of others made me cut the picture up in a rage! (Brett 1933: 275). Lawrence had condoled with her when the Brewsters ‘snubbed your Jesus’ (5L 390). But when Brett showed him the painting in her hotel room on Capri in March 1926 (Ellis 1998: 291):

‘You look at it in astonishment; then you laugh and say quickly:

“It’s a good idea, but it’s much too like me—much too like.”

“I know,” I reply, “but I took the heads half from you and half from John the Baptist.”

“It’s too like me,” you repeat abruptly. “You will have to change it.” …

“It is you,” I say.

“Perhaps,” you answer grimly. (Brett 1933: 275)

Brett adds “some day I will paint it again”. This day came thirty years later in 1963, when she named it after Lawrence’s 1927-8 novella ‘The Man Who Died’ (Hignett 1984: 208-9). In this the resurrected Christ forms a sexual relationship whilst ‘the all-tolerant Pan watched’ (VG 151); by the time the painting was resurrected, apparently in near-identical form,[1] Lawrence was also a man who had died, yet was in more ethereal ways living on.

He had remained an important part of Brett’s life over the intervening decades, not least because she continued to live on his former ranch, where she came to be visited by ‘A constant stream of scholars, writers and Ph.D. students’ with a ‘belief that the glory that had been reflected on Dorothy Brett would be transferred to them’ (Hignett 1984: 264; 9). Three years before she revived her painting, the British unbanning of Lady Chatterley’s Lover had stoked still more of the facile Lawrentian idolatry she professed to deplore (214). She clearly considered her own work of iconisation of 1926/63 to stand distinct.

Yet her choices of icons were obvious ones. Numerous features of Lawrence suggested contemporary understandings of each or both gods, to her as to many, in Lawrence’s lifetime, the 1960s and since. Christ-like he preached an idiosyncratic vision of salvation both parabolically and explicitly, denounced hypocrisy and materialism, prioritised content over form and soul over intellect, liked children and communal living, prophesied destruction, was poor and physically weak, died in pain and believed in a kind of resurrection. Yet he was not humble, non-resistant, humourless or asexual. Pan-like he could also be a satiric outsider, was deeply connected to nature, and believed in the importance of sex and in man as an animal. His physical and behavioural resemblances to Christ were remarked by numerous contemporaries: several accounts of Lawrence’s December 1923 dinner at the Café Royal liken it to a Last Supper, with Lawrence as Christ and John Middleton Murry as Judas (Nehls 1958: 295-304; Ellis 1998: 148). But he could also suggest Pan; Brett recalls watching him sleeping on Capri: ‘As I watch you … A leopard skin, a mass of flowers and leaves wrap themselves round you. Out of your thick hair, two small horns poke their sharp points; the slender cloven hoofs lie entangled in weeds’ (1933: 286).

The two gods are mutually antagonistic according to the ancient story that at ‘At the beginning of the Christian era, voices were heard off the coasts of Greece, out to sea, on the Mediterranean, wailing: “Pan is dead! Great Pan is dead!”’ (MM 155). Pan was therefore often identified with Satan, with whose conventional representation his own shares horns and hooves. Their opposition is rendered the more striking, however, by their similarities: bearded (‘the beard’ is a strong Lawrentian indicator in biofiction, as Lee M. Jenkins relates in her Chapter in this volume), slender, déclassé outsiders who live close to nature and die young. Consequently, not only could Lawrence be represented as either Pan or Christ, but many of his aspects – for example as a preacher of sexual honesty or a bohemian rebel – could be aligned with either, or both.

Brett’s Christ resembles none of those described in ‘Christs in the Tyrol’ (1913); he does not stare ‘stubbornly’ like a ‘Bavarian peasant’ (TI 43), nor is he in ‘bitter despair’ (44). He more resembles one of the ‘others’ which Lawrence speculated might also have existed on the cross: ‘one who looked at them and thought: “I might be among you … But I am not, I am here. And so——”’. Lawrence closed his essay: ‘And I suppose we [presumably the English] have carved no Christs, afraid lest they should be too like men, too like ourselves’ (47). In Brett’s case, in painting Lawrence, she found herself painting gods. Her Pan distorts the Biblical narrative just as much as her own, and Lawrence’s, depictions of Christ. His gesture is ambiguously one of teasing and goodwill in offering physical joy (represented by the grape, in contrast to Mark’s myrrh [15.23], Matthew’s gall [27.34] and John’s vinegar [19.29]). In ‘The Man Who Died’ Christ as it were accepts Pan’s proffered grapes and so becomes him – a Roman overseer calls him ‘the goat’ (VG 162) – but in the painting each god has his own, separate validity: each has his own flowers.[2] Although Christ is bound, and Pan is almost centred, Christ’s height is greater, the sun amplifies his halo, and his flowers give their whiteness to Pan’s horns, and cover his quiescent phallus.

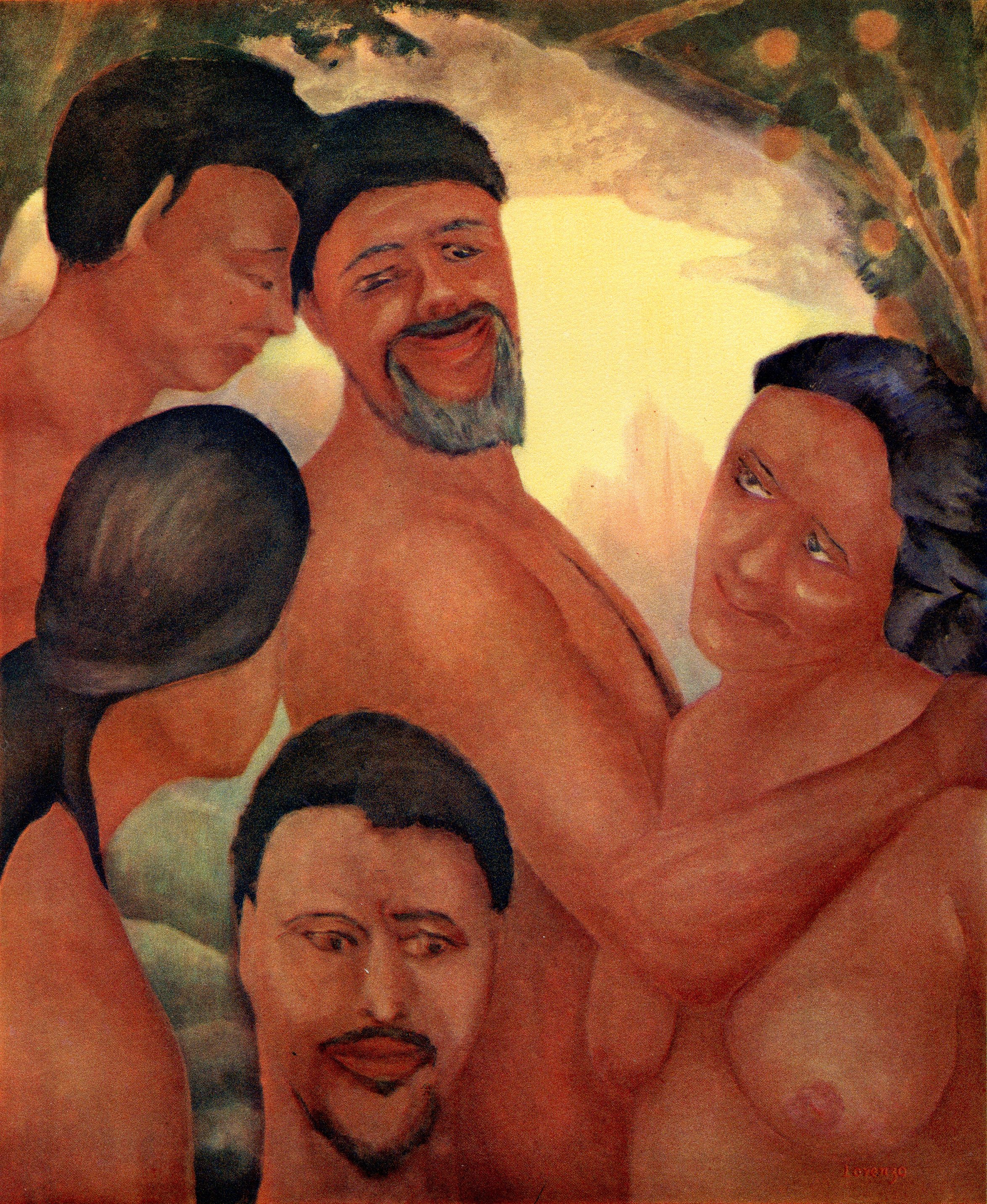

Certainly the relationship is more balanced than in the painting which Lawrence started the year after seeing Brett’s. He described ‘Fauns and Nymphs’ as ‘a nice canvas of sun-nymphs laughing at the Crucifixion – but I had to paint out the Crucifixion’ (Sagar 2003: 47). Here the triumph of the Pan-like is so total as to obliterate the crucifixion even beyond the reach of its mockery.

D. H. Lawrence, ‘Fauns and Nymphs’, 1927

Like Nietzsche’s, Lawrence’s obsession with Christ was one as rival and corrector, and by Pan Lawrence understood what Christ had failed to value or understand. Nonetheless, if one considers Lawrence’s writings more broadly, a range of relationships between the Pan-like and Christ-like emerge. Some are uncomfortable, and resemble the combination which Lawrence attributes to the Murry avatar in his 1924 story ‘The Last Laugh’: ‘he seemed like a satanic young priest … A sort of faun on the Cross, with all the malice of the complication’ (WWRA 123). Others, however, evoke the separateness-with-connection, and difference-without-agonism, which Brett’s painting depicted – notably ‘The Overtone’, in which the young woman Elsa desires both Christ and Pan, because ‘I am a nymph and a woman, and Pan is for me, and Christ is for me … To Pan I am nymph, to Christ I am woman. And Pan is in the darkness, and Christ in the pale light’ (SM 16).

This Chapter will use these relations in Lawrence’s writing as a context in which to understand why and how he has so often not only been treated as an icon but a deity – especially Christ or Pan. This is not to deny a Lawrentian quiddity irreducible to either god or to any relationship between them; a concentration on the Christ/Pan axis tends to obscure Lawrence’s political interests, for example. Nonetheless, it has often been remarked that Lawrence is contradictory, and has been deified; I suggest that Brett’s double portrait suggests a way of linking the two.

It is first worth mentioning, however, the relationship between iconisation and deification. An ‘icon’ expanded its meaning from a visual depiction (especially of divinity) to ‘A person or thing regarded as a representative symbol’ or one ‘considered worthy of admiration or respect’ in the early 1950s (OED draft addition 2001), just in time for the take-off in Lawrence’s standing as an icon metonymic of successful working-class men (Baldick 2001: 263), and as a thinker ‘considered worthy of admiration or respect’ (as he was represented by F. R. Leavis [1955]). It is with the latter sense of ‘icon’, which refers to the signified rather than the signifier (‘icon’ tout court, rather than ‘icon of’) that this Chapter is principally concerned. Even within his lifetime Lawrence became sufficiently famous as to be visually recognisable (generating, and thanks to, ‘icons’ in the pictorial sense). He himself strongly satirised the appetite for such stardom, notably in Clifford Chatterley’s worship of ‘success: the bitch-goddess!’ (LCL 50). He also criticised the deification of others, including Christ (‘I cannot believe in a church of Christ’) and authors (notably Dostoevsky; RDP 385). As we shall see, however, he himself did much to invite such a response. As early as 1932, his German advocate Wilhelm Emanuel Süskind ‘wrote that in Lawrence we have the unique case of a modern writer who, even outside his own language community and solely as a writer, had formed groups of devoted disciples’ (quoted in Jansohn and Mehl 2007: 2). The Chapter will focus on the first four decades of his reception history, until the ‘groups of devoted disciples’ began to significantly dwindle. More recent developments, however, will be considered in the final section.

Lawrence as Christ

Brett’s own memoir of Lawrence is, in Keith Cushman’s words, ‘the most adoring’ of those produced in the 1930s (2010: 125). Its present tense second-person address recalls a Protestant’s personal, conversational relationship with the risen Christ, whilst the memories recounted frequently present Lawrence in a Christ-like aspect. He enters the Café Royal ‘like a God, the Lord of us all, the light streaming down on your dark, gold hair’ (Brett 1933: 20). If her painted and pen portraits of Lawrence figure him as ‘D. H. Lawrence Superstar’, then her love for him, with its uncertain sexual element, anticipates the song of Mary Magdalene in the 1972 musical Jesus Christ Superstar: ‘I don’t know how to love him’.

In Son of Woman, of two years before, Murry’s presentation of Lawrence as ‘the anti-type of the man who is from the beginning, and will be to the end, his veritable hero – Jesus Christ’ (1931: 14) relied on their similarities as much as their differences: ‘only can Jesus can judge Lawrence, because he loved as Lawrence did’; ‘if he was crucified, as he surely was, it was for us that he was crucified’ (55). Indeed, his understanding of Christ seems to have been as much influenced by his knowledge of Lawrence as the reverse; according to his 1926 biography of Jesus: Man of Genius, ‘Jesus taught Life itself – not how to live – but Life’ (xiii); he valorised ‘something infinitely precious’, which ‘sometimes’ he called ‘Life itself’ (7). Catherine Carswell, in her prompt defence of Lawrence from this attack, cast Murry as Judas (and therefore, implicitly, Lawrence as Christ) (1981: 48). Aldous Huxley called Son of Woman a ‘curious essay in destructive hagiography’, yet the noun as well as the adjective is apt (1937: 332). Murry presents Lawrence too as a ‘thing of wonder’ who gives ‘birth’ to ‘spirit and love’ ‘in men’ (1931: 389). He not only presents Lawrence, like Christ, as a man without humour, but treats him in an entirely serious spirit, and never mocks.

In his 1937 essay on Lawrence, Huxley spliced Matthew Arnold’s 1873 definition of God (as ‘the enduring power, not ourselves, which makes for righteousness’ [1893: 43]) with Lawrence’s own vocabulary to say that, for Lawrence, ‘sex is something not ourselves that makes for – not righteousness … for life, for divineness, for union with the mystery’ (1937: 334). Leavis then recapitulated the phrase ‘that makes for’ in asserting that Lawrence ‘has an unfailingly sure sense of the difference between that which makes for life and that which makes against it’ (1955: 311). He also recycled the terms with which Murry had described both Christ and Lawrence: ‘a man with the clairvoyance and honesty of genius’ (1955: 110); a centre ‘of radiant potency – of life that irradiates people in whom the creativity is less powerful’ (1976: 152). With reason, Chris Baldick asserted that by the 1950s Leavis had ‘assumed the role of St Paul’ to Lawrence’s Christ (2001: 259).

On the cusp of the next decade, during the British Lady Chatterley trial, several defence witnesses argued for the novel’s compatibility with Christian morality, of which some attributed this to Lawrence’s nonconformist background. Defence QC Gerald Gardiner said that ‘this book was a passionately sincere book of a moralist in the Puritan tradition’, and implied that, like Christ, Lawrence had suffered injustice at his death from which a subsequent religion (which a proper study of ‘what it [LCL] really is’ would permit) would rescue him (quoted in Hyde 1990: 279). The Bishop of Woolwich Dr John Robinson, one of four Anglican clergymen who appeared for the defence, averred that it was a book which ‘Christians ought to read’ since it depicted sex as ‘something sacred, in a real sense as an act of Holy Communion’ (128: 127). The soubriquet for Lawrence as an icon of the sexual revolution, ‘Priest of Love’, drew on Lawrence’s own Christian vocabulary in a self-description of Christmas Day 1912, even whilst the term ‘Love’ turned euphemistically in the direction of Pan (1L 493).

The contrast of Lawrence’s posthumous deification with his previous vilification drew some satiric notice, as Jenkins notes in the context of her Chapter on biofiction: ‘in England the murder of genius was only a precautionary measure taken to ensure a posthumous canonization’ (Winter 1936: 14). Yet Leavis drew an important line: ‘I view with the gravest distrust the prospect of Lawrence’s being adopted for expository appreciation as almost a Christian by writers whose religious complexion is congenial to Mr Eliot’ (1955: 311), recognising that ‘the insight, the wisdom … that Lawrence brings’ (15) diverged importantly from Christ’s own. The distance may be measured particularly clearly in those of Lawrence’s writings that treat the pagan god, Pan, which for Lawrence represented the necessary corrective to Christ – writings which in turn inspired alternative responses to Lawrence.

Lawrence as Pan

‘The Last Laugh’ (1924) gives its eponymous laugh to what is strongly implied to be Pan; this being kills the story’s Murry character but vivifies the story’s Brett avatar (well might she paint Pan positively two years later). The being’s conflict with Christianity is direct; his wind wrecks a Hampstead church, plays its organ like ‘Pan-pipes’ and sends its altar cloth flying into the trees with which Pan is so strongly associated (WWRA? 131). This is Pan as an Antichrist – a satiric, laughing, revitalising and potentially-dangerous outsider. Several such aspects of Lawrence were valorised by critics whose thought had some overlap with fascism (Booth in his Chapter on Lawrence’s politics refutes the idea that Lawrence can himself be described as fascist). In 1941 the German Karl Arns praised him as ‘a rebel against English prudishness, intellectualism, bourgeoisie, the machine, democracy and Christianity’ (quoted in Jansohn and Mehl: 51).

Some of the same qualities were also valued by the working-class men, entering universities for the first time in large numbers in the 1950s, who took Lawrence as an icon of proletarian masculinity. As Raymond Williams observed, ‘If there was one person everybody wanted to be after the war, to the point of caricature, it was Lawrence’ (1977: 126); the Lawrence beards which they affected were arguably closer in spirit to Pan’s than Christ’s (the former more pointed, and therefore both more goat-like and more Satanic). The latter had been a provincial carpenter’s son who had conquered the world, but the former had a capacity for mockery, and for violating goddesses, which suited the Angry Young Men’s particular form of anger. Colin Clarke’s 1969 River of Dissolution explored Lawrence’s inward understanding of degeneration as an explicit counter to Leavis’s interpretation: ‘The Satanic Lawrence, or the Lawrence who finds beauty in the phosphorescence of decay, will be sought in vain in the pages of D. H. Lawrence: Novelist’ (xiv).

Lawrence’s embodiment of the Hampstead Pan’s laughing, puckish aspect in his brilliant acts of mimicry (described by John Worthen in his Chapter on ‘Performance’) was acknowledged by several works of biofiction (see also Jenkins’s Chapter), but recognition of the laughter in Lawrence’s works was slower to develop. In 1955 Leavis complained about the ‘absurd’ ‘view that he lacks a sense of humour’ (13). This view declined particularly after the publication of the complete text of Mr Noon in 1984, and the exploration of Lawrence and Comedy in a 2010 collection of essays (Eggert and Worthen). As recognition of Lawrence’s senses of humour has risen, so too has an apprehension of his resemblance to certain of his own conceptions of Pan, as explored by John Turner in the 2010 collection (70-88).

Two different conceptions of Pan are expounded in Lawrence’s ‘Pan in America’ (1924), of which the thesis is that Pan did not actually die ‘At the beginning of the Christian era’, but became ‘old and grey-bearded and goat-legged, and his passion was degraded with the lust of senility’ until he became ‘Old Nick … who is responsible for all our wickednesses, but especially our sensual excesses’ (MM 156). The original ‘great god Pan’ is a greater being, however, and Lawrence found him to be most honoured and alive amongst ‘the Indians’ who are most in contact with the universe (164). St. Mawr draws out this distinction when Lou tells Dean Vyner that he looks like Pan: ‘But I’m afraid it’s not the face of the Great God Pan. Isn’t it rather the Great Goat Pan!’ (SM 64). ‘Pan’ comes from ‘pasturer’ but Lawrence, like many, associated it with ‘all’ (VG 279). Several early critics of Lawrence praised Lawrence’s sense of connection to the living universe, and of these a few named Pan. J. C. Squire, in his 1928 review of the Collected Poems, said that ‘Mr. Lawrence might almost have been possessed by Pan’ (301).

Yet the ‘goat-legged old father of satyrs’ has been the form of Pan most invoked, implicitly or explicitly, by those who made the author of Lady Chatterley’s Lover an icon of the sexual revolution (SM 64). Not only is Lady Chatterley’s Lover in many countries the one work by Lawrence which most people can name, in France ‘as elsewhere in the world, the general public is certainly more familiar with the name of Lady Chatterley than with its creator’s’ (Katz-Roy 2007: 107). After the publicity caused by the Italian (1947), American (1959) and UK (1960) Lady Chatterley trials there was a flurry of translations of the novel into European languages (Jansohn and Mehl 2007: xxxi-xxxiii). It was widely received as celebrating freedom of love and of pornography, in a manner still further removed from that novel’s desiderata than is the facile, sensationalist ‘jazzing’ which is condemned in its representation of Venice (LCL 259). This response persisted despite the disappointment of some of those who approach the book in such a spirit, as Lawrence saw happening in his own lifetime (310). In 1965 Tom Lehrer asked in a song entitled ‘Smut’: ‘Who needs a hobby like tennis or philately? / I’ve got a hobby: rereading Lady Chatterley’. Two years later Philip Larkin struck a similar note by announcing that ‘Sexual intercourse began’ only after ‘the end of the Chatterley ban’ (2003: 146). In Perestroika and post-Soviet Russia, where new translations appeared in 1989 and 2000, the novel was (mis-)aligned with the strenuously- if inaccurately-Westernising pornification of society that pertained to that period (Jansohn and Mehl 2007: xxxviii, xli). More recently, ‘goat-legged’ humour generated The Mirror headline of 16thDecember 2005 concerning the new Ann Summers ‘Lady Chatterley’ lingerie range: ‘Who nicked Lady Chatterley’s Knickers?’. In more straightforward pornographic mode are the photo-illustrated, heavily abridged versions of the novel, such as that of Roger Baker (1990).

The relationship between the Christ-like and the Pan-like, which often emerges in responses to Lawrence, is that the former relates to form whereas the latter relates to content. Huxley perceived that he ‘could never forget, as most of us almost continuously forget, the dark presence of otherness that lies beyond the boundaries of man’s conscious mind’, but in preaching this, Lawrence inevitably resembled Christ, since Christ but not Pan was a preacher (1937: 333). This is the theological aspect of the crucial Lawrentian paradox of consciously extolling the virtues of unconsciousness. A similar tension exists in the shrine that Frieda and her third husband Antonio Ravagli built in 1935 for Lawrence’s ashes at Taos. Its form was more that of a chapel than a temple; Pan tended to be worshipped outdoors, and this supposedly contained the ‘shrine’ of Lawrence’s ashes; but the extent of the appropriateness of this resemblance, alongside the frisson of heterodoxy created by the substitution of Lawrence’s phoenix for the cross, fits with the tension between two gods that existed in Lawrence’s life, and which the scattering of Lawrence’s ashes on the mountainside (that Brett favoured), would not have acknowledged (Hignett 1984: 225).

Icons

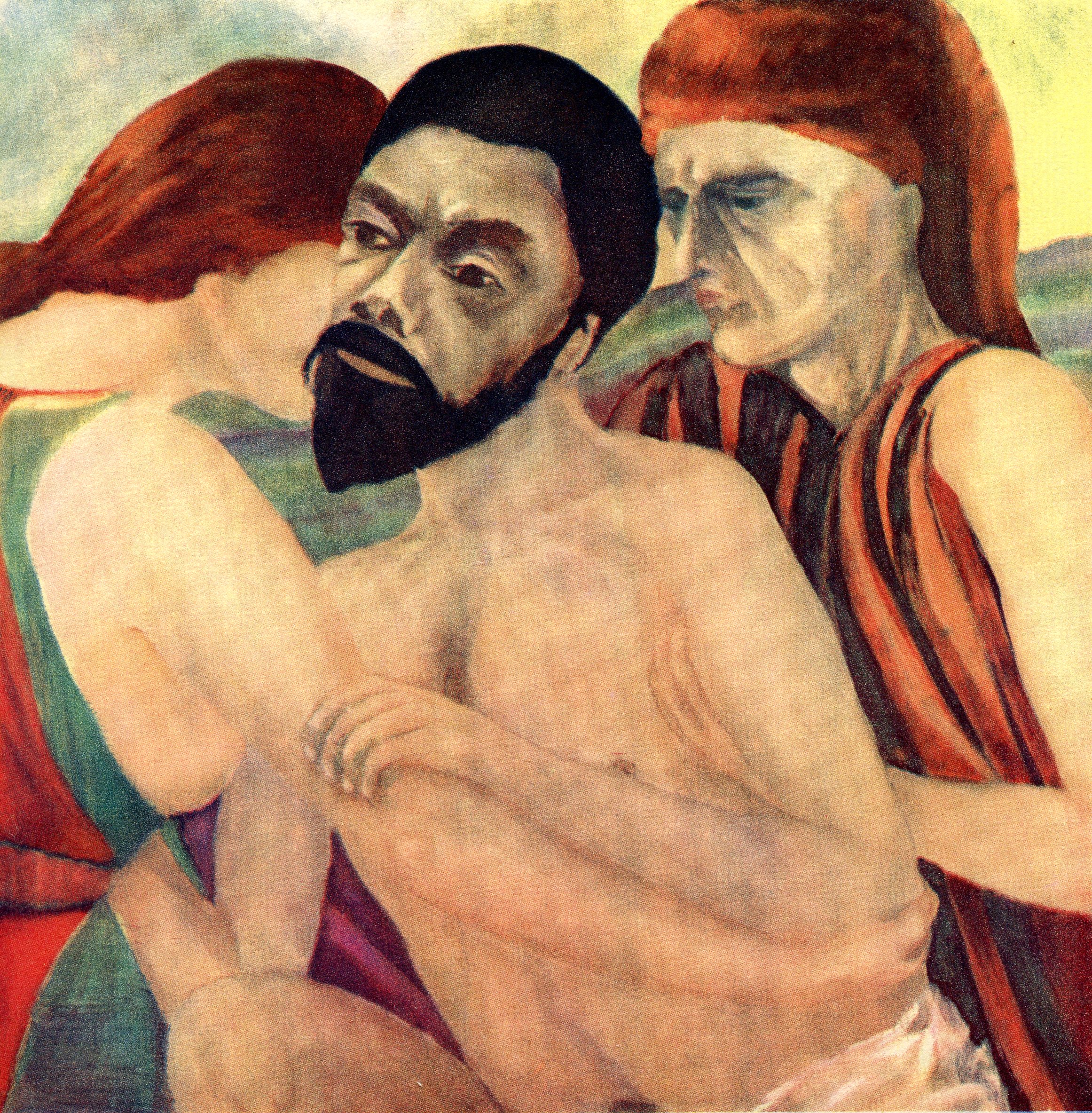

Unlike Brett, Lawrence never clearly represented himself as Pan, but did give his face to Christ, as in his May 1927 painting Resurrection.

D. H. Lawrence, ‘Resurrection’, 1927

Created at the same time as Part 1 of ‘The Man Who Died’, this shows a Christ who, although his eyes are still dim with death, appears physically robust enough to satisfy a Priestess of Isis in due course. Indeed, wherever Lawrence’s face is to be found in his paintings it tops a body more robust than his own. Lawrence’s painting therefore performs a similar critique of Christ as does his story (arguing that Christ over-sacrificed himself at the expense of his body, which is seen increasing in strength and potency over the course of the story).

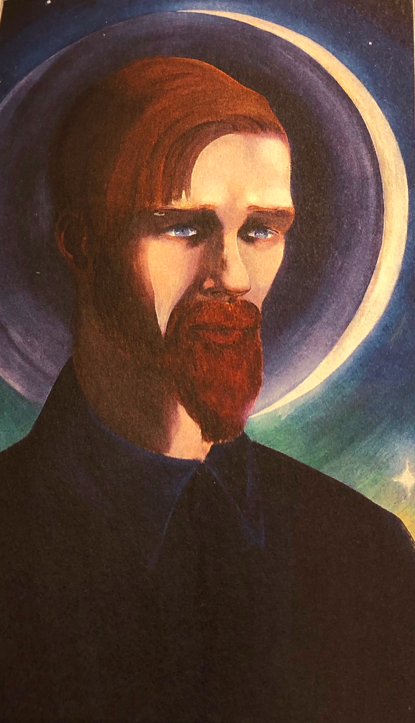

Brett’s 1925 portrait also splices Lawrence with an unorthodox vision of Christ (as her double portrait of the following year, which displaces Lawrence’s critique of Christ onto Pan, does not).

Dorothy Brett, Portrait of D. H. Lawrence with Halo, 1925

More than in Resurrection, the Lawrentian and the Christ-like exist in powerful dialogue with each other. The narrowed, slightly-stylised eyes, as in an Orthodox icon, gaze with pain to the viewer’s right, indeterminately at the state of the world and at his own fate. His halo is formed by a moon in near-total eclipse; soon he will be left in darkness, save for the star that burns prominently over his left shoulder, perhaps suggesting rebirth through its allusion to the Nativity. He is dressed, as Ellis notes that Lawrence rarely was, as ‘the artist’, in a navy shirt and black smoking jacket (1992: 163). Brett is therefore conflating the godlike and the artistic, but conceiving of both in their toughest aspects. The similarity of the three-quarter profile, colour of hair and shape of beard to that of the Christ of the following year’s double-portrait with Pan emphasises the contrasts. Assertively clothed rather than semi-naked, composed rather than startled, potent rather than crucified, and in the present rather than the past, this Lawrence clearly matches Christ’s capacity for grief, but has a different set of solutions for the modern world.

By contrast, several much-reproduced photographs taken near the end of Lawrence’s life evoke more traditional images of Christ. Whenever he was photographed to a standard sufficiently high to invite reproduction, he tended to be alone and serious; in traditional iconography (from ancient Greece, and throughout the history of Christian art), often Pan, but rarely Christ, smiles. Publicity photographs did not demand smiling but did require a few seconds’ pause (in 1928 the society photographer Robert H. Davis demanded of him six), which cannot capture a sincere smile (Ellis 1992: 166). Catherine Carswell, who managed to ‘take a snapshot’ of a laughing Lawrence in Florence in 1921, said that ‘I am very glad to have the picture now. It is, I think, a misfortune that by far the most of the photographs and portraits of Lawrence show him as thoughtful – either fiercely or sufferingly so’ (1932: 167).

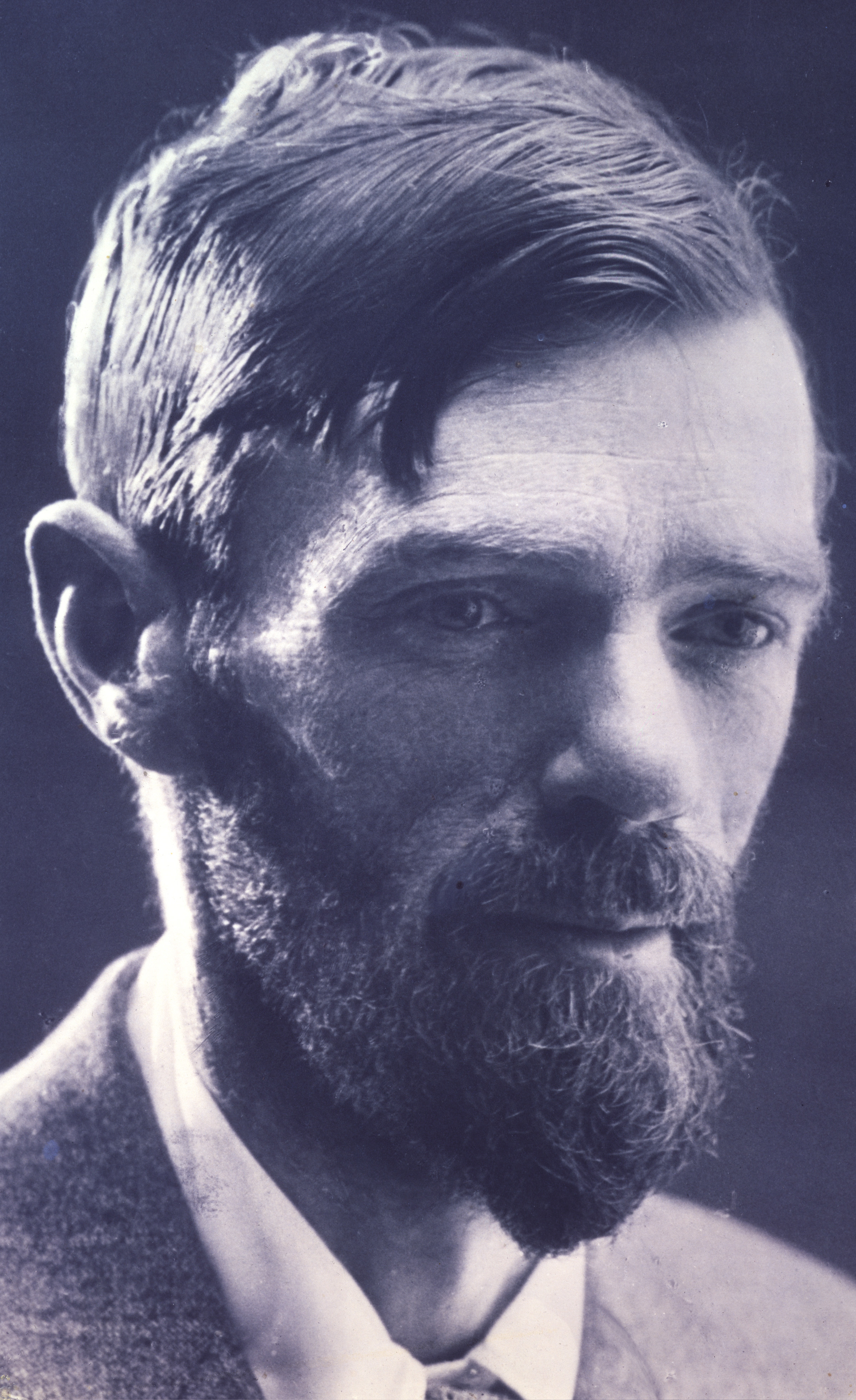

In 1928 Robert H. Davis made a number of such photographic portraits at Pino Orioli’s bookshop in Florence. One was used on the dustjacket of Last Poems (1932) and Volume III of the Nehls biography; it was photographs such as these that Geoff Dyer had in mind when he commented that ‘The closer he came to die’ (when ‘It was possible to discern in him the profile of his approaching death’), ‘the more he looked like D. H. Lawrence’ (1998: 37). But the studio photograph taken in June 1929 by Ernesto Guardia for the frontispiece of Pansies ‒ also chosen by Aldous Huxley for his 1932 selection of Lawrence’s letters, and for the back of many Penguin paperbacks in the 1950s and 60s – contains no hint of the crucifixion.

Ernesto Guardia, Portrait of D. H. Lawrence, 1929

The eyes are mild, loving and understanding, the lips are pressed gently in thought, and the white light which illumines his cheek and forehead is at one with his clerically white collar. An almost equally famous photograph taken at the same sitting shows him gazing, far-seeing and straight before him, with a slight smile of joyful anticipation. He is lit both behind and in front and, for all the obtrusively quotidian nature of his jacket, shirt and tie, he could be gazing at heaven.

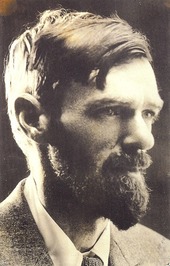

Ernesto Guardia, Portrait of D. H. Lawrence, 1929

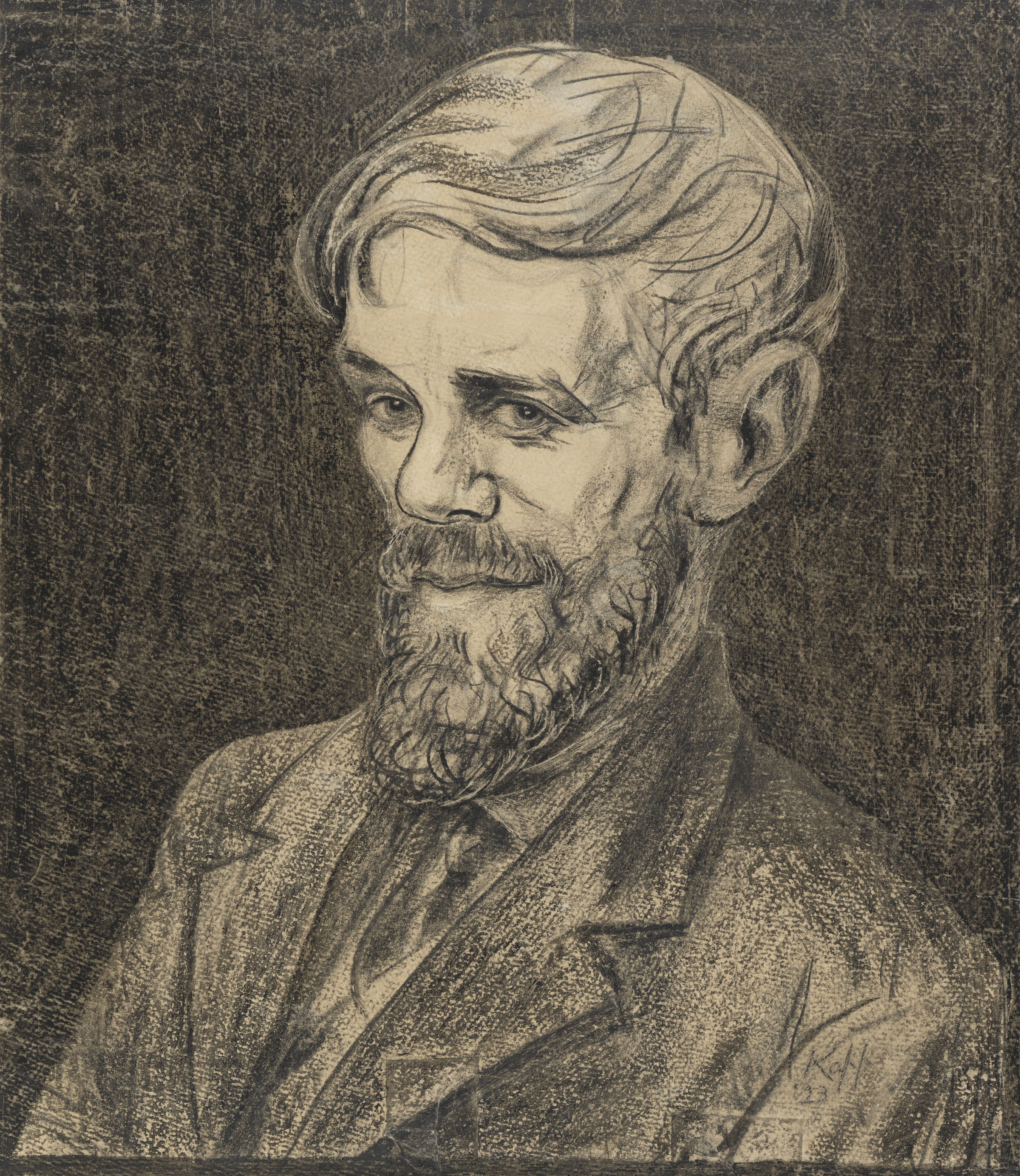

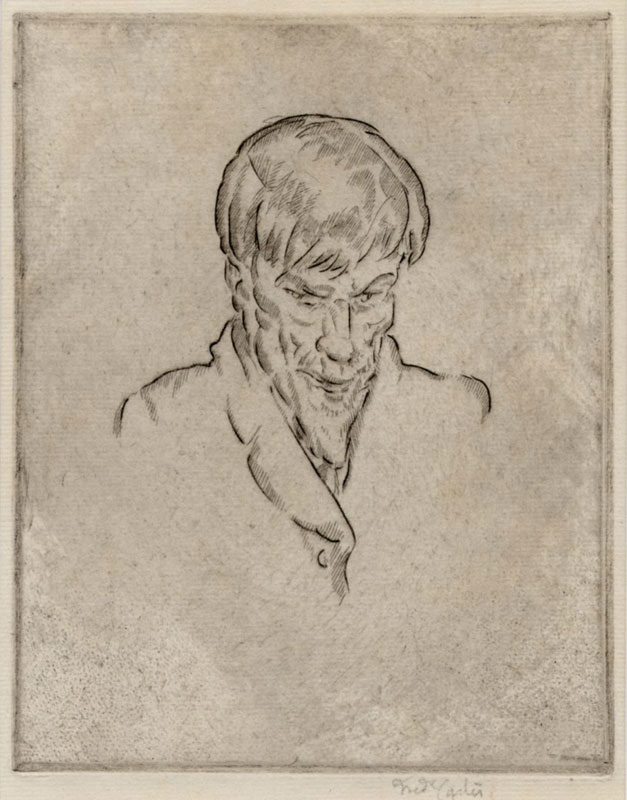

As far as I am aware, only Brett’s double portrait represents Lawrence as literally goat-legged, and no portrait from his lifetime represents him as metaphorically so, ‘the Great Goat Pan!’ (SM 64). Perhaps the closest is a 1923 three-quarter profile in chalk by Edmond Xavier Kapp in which he looks indeterminately at and through the viewer; his mouth is curved in a bow, he keeps his own counsel, but has the appearance of having many things up his sleeve.

Edmond Xavier Kapp, Portrait of D. H. Lawrence, 1923

All is raffish curves: the curly fringe, archly raised brows, proletarian nose, bowed mouth, and beard which in its curliness and length is pointedly that of Pan and not Christ. Here were have the strongest smile in a contemporary – perhaps any – non-photographic picture of Lawrence, underlining both the satiric and satyric sense which placed him on the side of Pan.

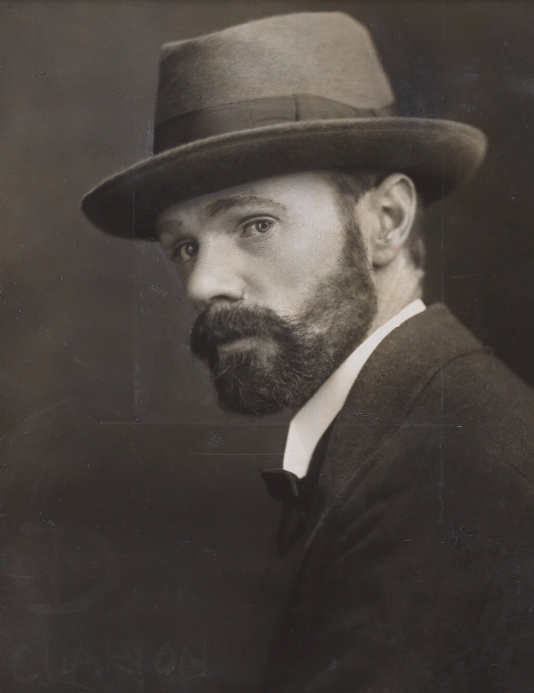

A few photographs, however, more strongly conjure the ‘power to blast’ of Pan the revolutionary outsider (MM 156). One is the much-reproduced 1915 studio portrait of Lawrence in a hat looking over his left shoulder.

Elliott and Fry, Portrait of D. H. Lawrence, 1915

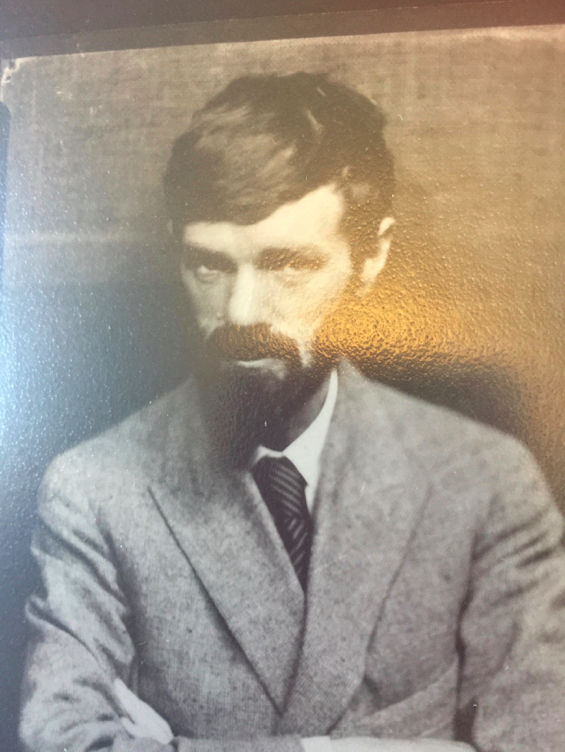

The stance is that of a sceptical, slightly hostile assessor of what is going on, confident in his immaculate suit, faintly gangsterish trilby and strongly-bearded chin. Half of his face is in shadow; he is not entirely knowable. He is reckoning up a fight that he has on his hands – but fight he will. This was selected by me for the 2017 International D. H. Lawrence conference poster in order to invite consideration of Lawrence as a somewhat dangerous denizen of London (as is the Pan of ‘The Last Laugh’), rather than a Christ-like provincial shepherd. Similar considerations may have influenced the choice of same image for the cover of Tom Paulin’s 2017 Faber selection of Lawrence’s poems. Still more threatening are the studio photographs requested by Lawrence’s American publisher Thomas Seltzer in August 1923, in which Lawrence has crossed arms, sunken cheeks, lowered brows, and eyes flinging challenge at the camera.

Studio portrait of D. H. Lawrence, 1923

His conventional dress seems to be worn as though in defiance and, as Brett imagined when they were on Capri, one can almost imagine horns emerging through his hair.

There exists one portrait which presents him as Pan-like in the most sinister sense, an etching (of which there are several versions) by Frederick Carter made around 1930.

Frederick Carter, Portrait of D. H. Lawrence, 1930s

His beard is pressed on his chest, his eyes look malevolently and panoptically in two different directions, and his lips are compressed into a frown-cum-grin. This Lawrence is plotting serious mischief with great concentration. But the majority of unflattering portraits of Lawrence suggest no deity whatsoever. When these are used to illustrate unflattering commentaries on Lawrence, the fact that they are not the ‘iconic’ images gives the very choice an iconoclastic frisson. For example, Mabel Dodge Luhan chose a 1924 Mexico City studio portrait for the frontispiece of her relatively unadoring 1932 memoirs. His back is to the wall, he looks down and to the side apparently in fear, and he has nothing to offer. Murry reiterated his purported taking of Lawrence at his own word in Son of Woman by using Lawrence’s 1929 self-portrait as his frontispiece (which had also been used in the first edition of Pansies). Well might Lawrence have said of this picture: ‘Alas, drawing my own face is unpleasant to me’ (Sagar 2003: 83). The face is concave with worry, there is a slight but crazed squint, and the mouth is part open in consternation. The tie ridiculously suggests an extension of the beard, but also, with its heavy knot, suggests a noose worn around the neck prior to an execution.

Several informal photographs, however, simply present Lawrence at peace with his circumambient universe, and therefore in touch with what Lawrence understands by ‘the Pan-mystery’ (MM 162). Brett’s memoir is illustrated by eight photographs taken in New Mexico, of which all show him outdoors, and three feature animals: a horse on whom he sits (96), a cat whom he holds (256) and a cow whom he milks (225). In the last of these his head is buried in the curve of Susan the cow’s right flank; his stance is of utter concentration as he doubtless feels ‘the pulse of the blood of the teats of the cow[s] beat into the pulse of [his] hands’ (R 10), and he seems as if he could be ‘still within the allness of Pan’ (MM 158). These images, however, are not those by which he is known.

Iconoclasm

One consequence of Lawrence’s deification has been that many of the attacks on him have addressed the deified versions of him. This is what I shall here call iconoclasm, since the denigration is not so much of the signified author as of the signifying icon (though in the denigrators’ minds the two may be confused). Such attacks tend to fall into two categories, those which accuse Lawrence of resembling Christ or Pan, and those which attack him for failing to resemble them – thus respectively condemning him by negative association with, and critiquing his alleged pretensions in relation to, these gods.

Lawrence was aware that he was ridiculed for his Christ-like aspects. In the year after he was painted as Christ in Brett’s double portrait, a photograph was taken of him wearing what appears to be a paper bishop’s mitre; his face expresses uncertain enjoyment at the joke.

D. H. Lawrence in 1927

In Women in Love he converted a real incident of an acquaintance’s parodic recitation of his poems in the Café Royal into a recitation of (Lawrence avatar) Birkin’s letters. The parodist’s friends respond: ‘It almost supersedes the Bible –’; ‘He thinks he is the Saviour of man’ (WL 383-4). One can hear in the last the tone of the high priest: ‘he made himself the Son of God’ (John 19: 7). Certainly Lawrence was trying to supersede the Bible; he said that with The Rainbow he wanted to create a ‘kind of Bible for the English people’ (Worthen 1981: 21). But it is not clear that Women in Love’s mockers would mock any the less were his writing tosupersede the Bible, which is presumably to them also an object of ridicule. To resemble Christ in his preaching may be for such critics as much a criticism of Christ for resembling Lawrence as the reverse.

By contrast, when Prosecutor Mervyn Griffith-Jones ridiculed the Bishop of Woolwich’s defence of Lady Chatterley’s Lover’s Puritanism by quoting the passage in which Connie thinks ‘“Beauty! What beauty! … the strange weight of the balls between his legs!” … That again, I assume, you say is puritanical? … Answer: Indeed, yes’ (Hyde 1990: 324-5), he was ridiculing the idea of Lawrence’s compatibility with Christianity, with no prejudice to the latter. (Murry, as we have noted, also found Lawrence wanting in comparison with Christ, but unlike Griffith-Jones took the comparison entirely seriously[1931: 54, 351, 372]).

Some people have been put off Lawrence by the religiosity of his followers, considering him to have been inappropriately deified. The novelist and editor Sigurd Hoel explained in 1930 why he would not publish Lawrence in the prestigious Yellow Series for Norwegian publisher Gyldendal as follows:

‘it is difficult to evaluate his contribution without taking into account the congregation with which he surrounded himself … vying with each other to praise, celebrate, embrace and adorn the master, the Messiah of the new dispensation. If the mixed fragrance of erotic perfume and the sweat of angst which is exuded from this circle is meant to be the scent of a new spring, then anybody would hastily pray for other seasons.’ (Fjågesund 2007: 247)

Wayne C. Booth, in his archly-titled ‘Confessions of a Lukewarm Lawrentian’, raises an eyebrow at Lawrentian idolatry even whilst he describes his rediscovery of its causes: ‘I find myself now returned from my un-Lawrentian prodigalities to confess my sins and to ask forgiveness’ (1990: 9). One also imagines that the laughter with which Brett acknowledges that her double portrait was received was similarly directed at its idolatry (1933: 275).

Just as some have condemned misguided worship of Lawrence as Christ-like, others have done the same for his worship as a lustful Pan. In 1957 Günter Blöcker wrote that ‘No author of the last fifty years has … found more false disciples than he’, but added in 1960 that ‘it is the logic of fame that ties the poet’s name to his most questionable product’ (quoted in Jansohn and Mehl 57-8). According to Alfred Andersch in 1968,

‘for many German intellectuals Lawrence is no more than the author of a kitschy novel [Lady Chatterley’s Lover]… owing to that trivial judgment, Lawrence’s masterworks are at present not obtainable in German bookshops, and people laugh at you when you maintain that the author of Sons and Lovers is an author of absolute greatness.’ (59-60)

Contrariwise, others have attacked Lawrence for failing to live up to Pan. Some have found in him under-acknowledged homosexual instincts, either because these entail a divergence from the full-blooded heterosexuality which they present him as valorising, or because he puritanically and conventionally denies the full range of his sexual experience, and therefore the amplitude of Pan in himself. Hugh Steven’s Chapter on ‘Politics and Art’ in the current volume contains elements of both analyses.

Such attacks contrast with those which condemn him for resembling Pan, as, I have argued above, Frederick Carter’s 1930 sketch does. The John Bull reviewer of Lady Chatterley’s Lover did not intend the soubriquet ‘this bearded satyr’ as a compliment (1928: 279). Such reactions pertained more in England than other European countries, however. In inter-War Germany it was understood that Lawrence was ‘opposed in conventional England more than in Germany for his alleged obsession with sex’ (Jansohn and Mehl 2007: 40). Further East, the Pan-like Lawrence was criticised from a Stalinist rather than a Christian viewpoint. Dmitry Svyatopolk Mirsky, who slightly knew Lawrence from his time in London in the 1920s, criticised him in his 1934 Intelligentsia of Great Britain for seeing himself as ‘more primitive and so more healthy than the bourgeoisie’; ‘It is no better than the reverse of the medal, a decadent bourgeois attraction to animal coarseness’:

It is one of the ‘heights’ of a very wide front of the literature of the upper intelligentsia produced by writers who have rejected society, lost faith in capitalist progress, and turned to the worship of what they consider to be the sempiternal phallic deity. (1935: 121-2)

Back in capitalist England a quarter-century later, Griffith-Jones, in his opening speech at the Chatterley trial, told the jury that

‘the prosecution will invite you to say that [the novel] does tend, certainly that it may tend, to induce lustful thoughts in the minds of those who read it … It commends, and indeed it sets out to commend, sensuality almost as a virtue.’ (Hyde 1990: 17)

Mirsky’s and Griffith-Jones’s critiques were reframed in feminist terms by Kate Millett in her 1970 Sexual Politics: ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover is a quasi-religious tract recounting the salvation of one modern woman … through the offices of the author’s personal cult, ‘the mystery of the phallus’ (1971: 238). Like Huxley, but from a critical standpoint, she identifies in Lady Chatterley’s Lover Christ-like form but Pan-like content: a description of Mellors’s penis is ‘the novel’s very holy of holies – a transfiguration scene with atmospheric clouds and lighting, and a Pentecostal sunbeam’. She names ‘the god Pan, incarnated in Mellors’ (242), and like Murry criticises Lawrence for failing to resemble Christ; in Aaron’s Rod’s she identifies the ‘attack on Christianity’ with ‘a need to debunk any system with egalitarian potentialities, sexual or social’ (277).

Conclusion: Resurrection

Yet Lawrence-as-deity has been more damaged by marginalisation than by explicit attack. The plunge in Lawrence’s stature and fame from the 1970s brings to mind the broken crucifix in the Alps which he saw in 1912, rhetorical arms swinging aimlessly in the wind, unheeded (TI 46-7). In part it has been the case that, as Margaret Drabble noted, ‘the mood of the 80s and 90s has been so hard-edged, so determinist-defeatist in some ways, so merciless in others and above all cynical – a world in which D. H. Lawrence does not fit’ (quoted Preston 2003: 30). That is, just as belief in the divinity of Christ has waned since Lawrence’s time (and interest in Pan has fallen from its Edwardian neo-pagan peak [3]), belief in Lawrence’s quasi-divine aspect – and even interest in attacking it – has diminished in what in the West has been a less religious age. In parallel, and paradoxically, his divinity has been obscured by such acceptance as his ideas have achieved; several of the desiderata of Lady Chatterley’s Lover have been achieved, not least through the fact of its unbanning.

During the 1985 centenary celebrations, Emile Delevanay said that ‘Even though the prophet, the guru, is already dated, the poet, the novelist, the short story writer, transcends the boundaries of his period’ (Katz-Roy 2007: 128). In doing so he was sending people back to the complexity of texts which disrupt any deification of Lawrence as Christ or Pan. In the same year the journal Études Lawrenciennes, and in the following year the annual Lawrence conference at the University of Nanterre, were established in order to foster precisely such study. Michael Bell exemplifies a contemporary reverent but non-deifying approach in suggesting that Lawrence should be taken as an index in the American philosopher C. S. Peirce’s sense of the word. Peirce (1839-1914) made a distinction between an index, which points to a referent elsewhere (as signposts and plaques beneath paintings do), and icons (which share features with the represented other, as portraits and maps do) (Savan 1993: 442). In my Introduction I stated that this Chapter was concerned mainly with Lawrence as a self-referential ‘icon’ tout court, rather than an icon of anything. An alternative approach is to take him as an index, which encourages us to look elsewhere:

‘Many are now educated confidently to look down on Lawrence as a thinker, and in a sense that is right. For no more than with Nietzsche would it be appropriate to look up to him in a spirit of discipleship. But any looking down should be a matter of questioning the ground on which one stands and the wholeness with which one thinks.’ (2007: 168).

In his 1924 essay ‘On Being Religious’ Lawrence figured the ‘Holy Ghost’ as a barking hound on the track of the now-elusive God, and encouraged his readers to accept ‘God’s own good fun’ in following the hound on the scent (RDP 192-3). Lawrence in his writings pursues this chase. His readers can either take him as their own Holy Ghost, or alternatively – as many now find easier – follow his example rather than his trajectory, and listen out for their own.

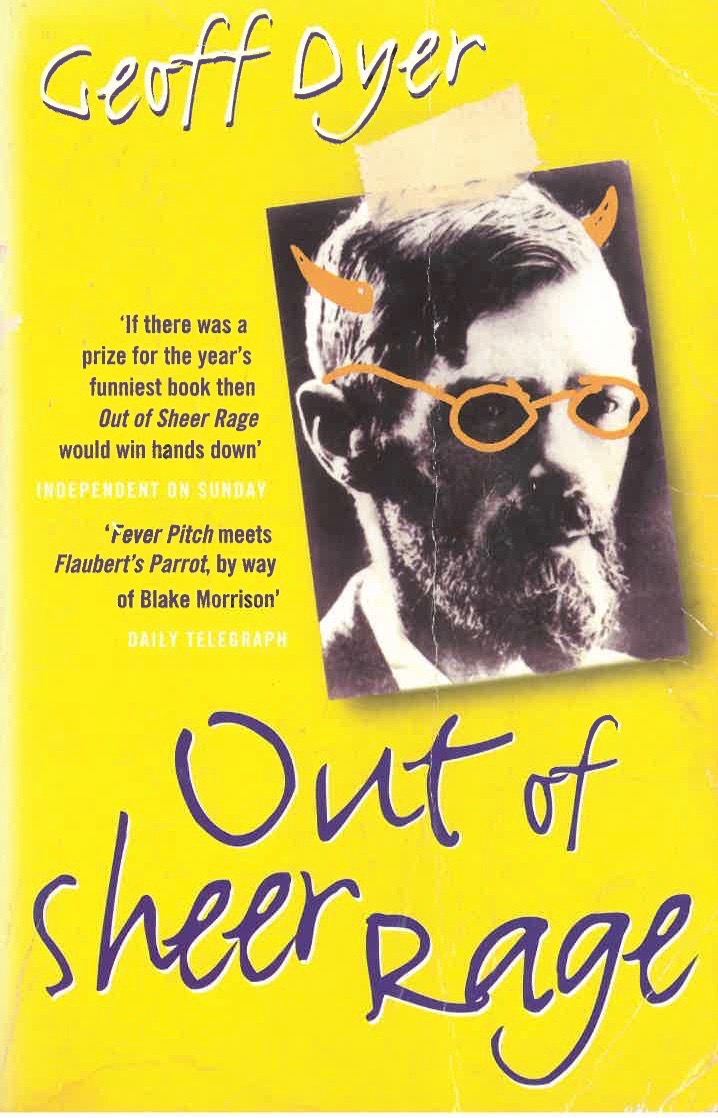

Yet although explicit, unembarrassed deification has now largely been abandoned, passionate appreciation and awe persist, sometimes under the guard of ostensible iconoclasm. Geoff Dyer is famed as an iconoclast of the deified Lawrence and of Leavis’s Lawrentian canon: ‘As for Women in Love, I read it in my teens and, as far as I am concerned, it can stay read … If we’re being utterly frank, I don’t want to re-read any novels by Lawrence’ (1997: 104-5). The 1998 front cover of Out of Sheer Rage, like Brett in 1963, represents Lawrence as Pan (by adding cartoonic Pan-horns to the 1929 Guardia photo portrait) – but in a spirit of iconoclasm rather than reverence ostensibly performs its failure to be the intended ‘homage to the writer who had made me want to become a writer’ (2), collapsing instead into the witty autobiography of that failure.

Cover of ‘Out of Sheer Rage’, Geoff Dyer, 1998

Yet the book’s original subtitle ‘In the Shadow of D. H. Lawrence’ not only acknowledges the depression into which that failure apparently threw the author, but the greater stature of his subject, about whom striking aperçus erupt without warning throughout the narrative. Dyer does not go so far in his explicit defence of Lawrence as Tony Hoagland, who in his poem of the same year confesses that:

‘On two occasions in the past twelve months

I have failed, when someone at a party

Spoke of him with a dismissive scorn,

To stand up for D. H. Lawrence.’ (1998: 31)

Rather, his admiration emerges as though backwards, in response and resistance to decades of less complicated admiration. Yet the book’s ultimate centre is Lawrence’s ‘Bejahung’ (Dyer 1997: 112): ‘saying yes’, or, as Aldous Huxley put it ‘For Lawrence … it was as though he were newly re-born from a mortal illness every day of his life. What these convalescent eyes saw [a world unfathomably beautiful and mysterious] his most casual speech would reveal’ (1937: 350). Dyer ends his book: ‘The world over, from Taos to Taormina … the best we can do is to try to make some progress with our studies of D. H. Lawrence’ (1997: 232).

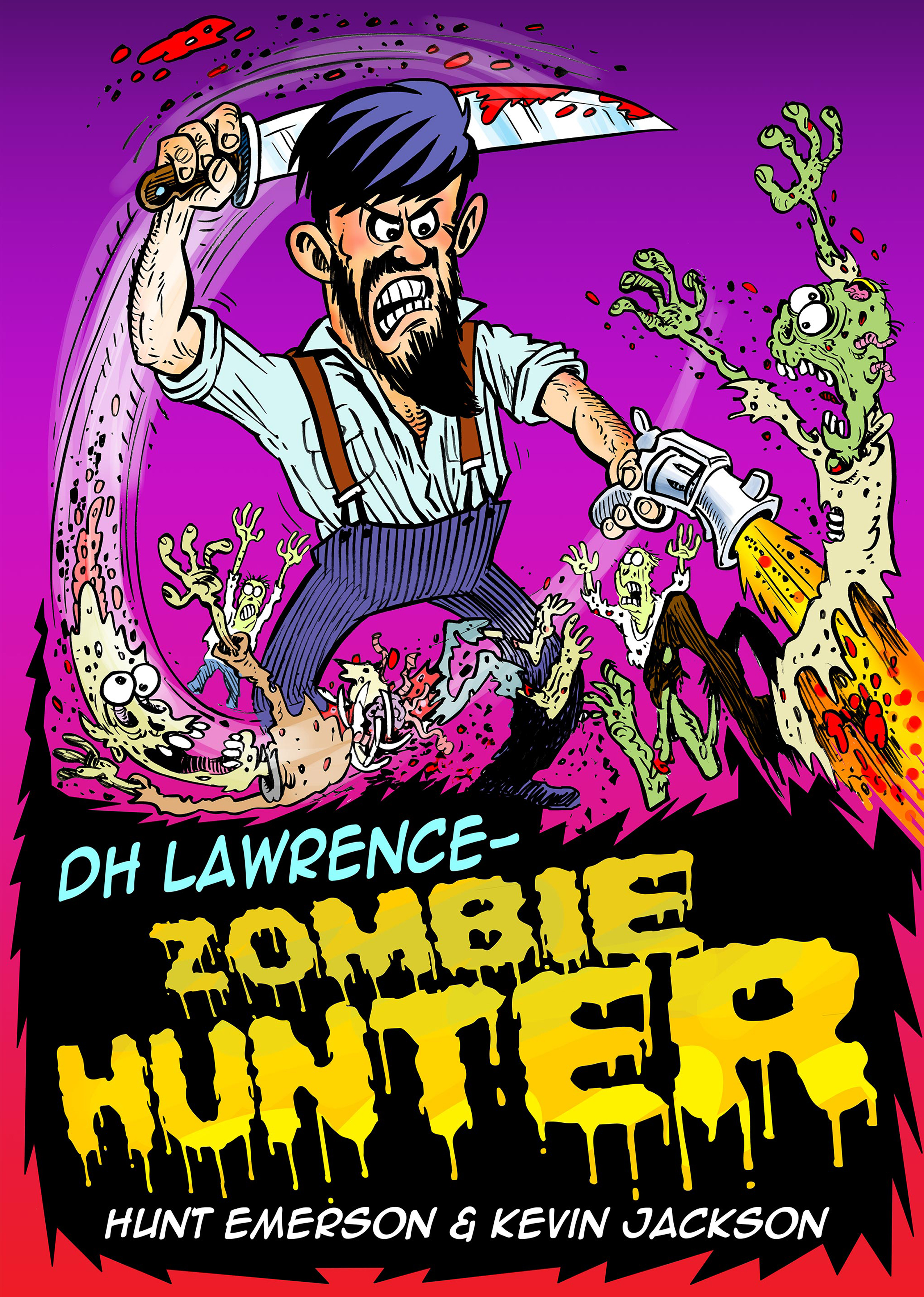

Out of Sheer Rage has a visual counterpart in Hunt Emerson (cartoonist) and Kevin Jackson’s (script) 2016 ‘D. H. Lawrence Zombie Hunter’. Here Lawrence is stylised with a black, cutlass-sharp beard, eyes crazed with anger, protruding ears and a brawny, sabre-wielding arm. As the prefatory note puts it:

‘Lawrence was the original Mr Angry – the Basil Fawlty of literary modernism. You name it, he was probably driven nuts by it … In this comic Lawrence’s ‘savage pilgrimage’ from nation to nation becomes a one-man war against the zombification of the human race.’ (n.p.)

Hunt Emerson, ‘D. H. Lawrence – Zombie Hunter’, 2016

The shrewd caricature undermines deification of Lawrence even whilst endowing Lawrence with (cartoonic) superhuman powers. Like Dyers’s book, this story manages to convey much perception and admiration, and concludes by asking, in relation to his proto-environmentalism, ‘Perhaps it’s time to take him seriously again?’ (n.p.). Certainly, ecocriticism has of late begun to recognise in Lawrence a major figure, as was evident at the 2018 Paris Nanterre conference entitled ‘Lawrence and the Anticipation of the Ecocritical Turn’. In stressing Lawrence’s intimate connectedness with the living universe, his participation in what he would call the Pan mystery is implicitly, if not always explicitly, acknowledged.

Dorothy Brett’s much-ridiculed painting of 1926, therefore, depicted an important dynamic not only of Lawrence’s thought but of his reception, as by 1963 she may have able to perceive. As recently as 2009-13 Glyn Bailey’s Broadway-style Lawrence: The Musical in part rehearsed a banalised Pan in its comic concentration on ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover / I’ve read it from cover to cover’, and a Christ-like Lawrence in a closing song that affirms its claim by the very fact of its performance: ‘I will rise like the Phoenix … I’ll never die again’. As this Chapter has hoped to show, understanding Lawrence as either Christ-like or Pan-like has involved denying parts of him. His story ‘The Overtone’, more than any of his other works, indicates the necessity of acknowledging both:

‘“Pan is in the darkness, and Christ in the pale light. “And night shall never be day, and day shall never be night. “But side by side they shall go, day and night, night and day, for ever apart, for ever together. “Pan and Christ, Christ and Pan.’ (SM 16)

Denying either in Lawrence as a whole can lead to misdirected deification, or irrelevant iconoclasm, of him. This was particularly apparent at the Lady Chatterley trial, which consisted of a battle between the defence’s and prosecution’s respective presentations of him as overwhelmingly Christ-like, and reprehensively Pan-like.

Although deification is now relatively out of cultural and critical vogue, so too is the aggressively deconstructive high theory which Dyer’s book deplores (1997: 100), and passionate and joyful admiration – if only of Lawrence as index rather than icon – persist. ‘A Lawrentian’ is not the equivalent term to ‘a Joycean’ in that the former is far more likely than the latter to attribute to their author inspiration for living. The name of the international online Lawrentian discussion group ‘Rananim’ balances modest irony (it is far from what Lawrence had hoped for under the name) with the good faith that helping each other with our ‘studies of D. H. Lawrence’ is the closest that we can come to his hopes. Many of his readers, who would resist any idea of deification, continue to feel, as Catherine Carswell did in 1932, that ‘His emblem, the phoenix, has not played him false. If it be true of any man it is true of him, what he said himself – “the dead don’t die. They look on and help”’ (292).

Works Cited

Arnold, Matthew (1893, orig. 1873), Literature and Dogma, London: Smith, Elder, & Co.

Baker, Roger, ed. (1990), D. H. Lawrence ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’, n. p.: Loveline Publishing Limited.

Baldick, Chris (2001), ‘Post-mortem: Lawrence’s Critical and Cultural legacy’, in

The Cambridge Companion to D. H. Lawrence, ed Anne Fernihough, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 253-70.

Bell, Michael (2007), Open Secrets: Literature, Education and Authority from J-J. Rousseau to J. M. Coetzee, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Booth, Wayne C. (1990), ‘Confessions of a Lukewarm Lawrentian’, in The Challenge of D. H. Lawrence, eds Michael Squires and Keith Cushman, Madison and London: The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 3-8.

Brett, Dorothy (1933), Lawrence and Brett: A Friendship, London: Martin Secker.

Carswell, Catherine (1981 [orig. 1932]), The Savage Pilgrimage: A Narrative of D. H.

Lawrence, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clarke, Colin (1969), River of Dissolution: D. H. Lawrence & English Romanticism,

London: Routledge.

Cushman, Keith (2010), ‘Indians, an Englishman, and an Englishwoman: Lawrence’s and

Dorothy Brett’s Representations of Indian Ceremonial Dancing’, in ‘Terra Incognita’: D. H. Lawrence at the Frontiers, eds Virginia Crosswhite Hyde and Earl G. Ingersoll, Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, pp. 112-30.

Dyer, Geoff (1998), Out of Sheer Rage: In the Shadow of D. H. Lawrence, London: Abacus.

Edwards, Sarah (2017), ‘Chapter 1: Dawn of the New Age: Edwardian and Neo-Edwardian Summer’, in Edwardian Culture: Beyond the Garden Party, eds Samuel Shaw, Sarah Shaw, Naomi Carle, London: Routledge. Ebook.

Eggert, Paul and John Worthen, eds (2010), Lawrence and Comedy, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Ellis, David (1998), D. H. Lawrence: Dying Game 1922-1930, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Ellis, David (1992), ‘Images of D. H. Lawrence: On the Use of Photographs in Biography’,

in The Portrait in Photography, ed. Graham Clarke, London: Reaktion Books, pp. 155-72.

Emerson, Hunt and Kevin Jackson (2016), ‘D. H. Lawrence: Zombie Hunter’, in Dawn

of the Unread, Nottingham: UNESCO City of Literature and Spokesman.

Fjågesund, Peter (2007), ‘In Hamsun’s Shadow: The Reception of D. H. Lawrence in

Norway’ in The Reception of D. H. Lawrence in Europe, eds Christa Janssohn and Dieter Mehl, London: Continuum, pp. 244-54.

Hoagland, Tony (1998), ‘Lawrence’ in Donkey Gospel, Minneapolis: Graywolf, p. 31.

Huxley, Aldous (1937), ‘D. H. Lawrence’, in Stories, Essays & Poems by Aldous Huxley,

London: J. M. Dent & Sons, pp. 331-52.

Hyde, H. Montgomery, ed. (1990), The Lady Chatterley’s Lover Trial, London: The Bodley

Head.

Janssohn, Christa and Dieter Mehl, eds (2007), The Reception of D. H. Lawrence in Europe,

London: Continuum.

John Bull (1928), review of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, in D. H. Lawrence: The Critical

Heritage, ed. R. P. Draper, London: Routledge, 1970, pp. 278-80.

Katz-Roy, Ginette (2007), ‘D. H. Lawrence in France: A Literary Giant with Feet of Clay’,

in The Reception of D. H. Lawrence in Europe, eds Christa Janssohn and Dieter Mehl, London: Continuum, pp. 107-37.

Lane-Fox, Robin (2019), email correspondence with the author.

Larkin, Philip (2003), Collected Poems, London, Faber & Faber.

Leavis, F. R. (1985, orig. 1955), D. H. Lawrence: Novelist, London: Peregrine.

Leavis, F. R. (1976), Thought, Words and Creativity: Art and Thought in Lawrence,

London: Chatto & Windus.

Luhan, Mabel Dodge (1932), Lorenzo in Taos, London: Martin Secker, 1933.

Millett, Kate (1971), Sexual Politics, London: Virago.

Mirsky, D. S. (1935), The Intelligentsia of Great Britain, trans. Alec Brown, London: Victor

Gollancz.

Murry, John Middleton (1926), Jesus: Man of Genius, New York and London: Harper.

Murry, John Middleton (1931), Son of Woman, London: Jonathan Cape.

Nehls, Edward (1958), D. H. Lawrence: a Composite Biography, vol. II 1919-1925,

Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Preston, Peter (2003), ‘“I am in a Novel”: Lawrence in Recent British Fiction’, in D. H.

Lawrence: New Worlds, eds Keith Cushman and Earl G. Ingersoll, London:

Associated University Press, pp. 25-49.

Sagar, Keith (2003), D. H. Lawrence’s Paintings, London: Chaucer Press.

Savan, David (1883), ‘Peirce, C(harles) S(anders)’, in Encyclopedia of Contemporary Literary Theory: Approaches, Scholars, Terms, ed. Irena R. Makaryk, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993, pp. 441-2.

Squire, J. C. (1928), Review of D. H. Lawrence Collected Poems in D. H.

Lawrence: The Critical Heritage, ed. R. P. Draper, London: Routledge, 1970, pp.

299-302.

Williams, Raymond (1979), ‘The English Novel from Dickens to Lawrence’, in Politics and

Letters: Interviews with New Left Review, London: NLB, pp. 243-70.

Winter, Keith (1936), Impassioned Pygmies, New York: Doubleday, Doran and Company.

Worthen, John, ed (1981), The Rainbow, D. H. Lawrence, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Notes

[1] Brett had saved the original faces, and the only discrepancy between the description of her 1926 version and its successor is that in the latter’s background there is nothing resembling ‘the tower of Quattro Venti’ (1933: 275).

[2] Christ’s have yucca filamentosa leaves and giant lily-of-the-valley heads; Pan’s resemble chrysanthemums; none of these would be flowering when the mountains are snowcapped on the Amalfi coast, reinforcing the scene’s splicing together of different historical times (Lane-Fox 2019).

[3] Consider, for example, ‘the Neo-Pagans’, the group surrounding Rupert Brooke in Cambridge before the First World War, or the fact that Kenneth Grahame’s 1908 The Wind in the Willows includes an encounter of the animals with Pan (Edwards 2017: subsection ‘The Golden Age in Edwardian Literature’).

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Sue Reid for her wise and generous guidance on this Chapter, as on the whole process of editing this volume.

Abbreviations

Letters of D. H. Lawrence

1L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume I: September 1901–May 1913, ed. James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979).

2L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume II: June 1913–October 1916, eds. George J. Zytaruk and James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

3L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume III: October 1916–June 1921, eds. James T. Boulton and Andrew Robertson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984).

4L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume IV: June 1921–March 1924, eds. Warren Roberts, James T. Boulton and Elizabeth Mansfield (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

5L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume V: March 1924–March 1927, eds. James T. Boulton and Lindeth Vasey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

6L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume VI: March 1927–November 1928, eds. James T. Boulton and Margaret H. Boulton with Gerald M. Lacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

7L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume VII: November 1928–February 1930, eds. Keith Sagar and James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

8L The Letters of D. H. Lawrence Volume VIII: Previously Uncollected Letters and General Index, ed. James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Works of D. H. Lawrence

A Apocalypse and the Writings on Revelation, ed. Mara Kalnins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980).

AR Aaron’s Rod, ed. Mara Kalnins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

BB The Boy in the Bush, with M. L. Skinner, ed. Paul Eggert (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

EmyE England, My England and Other Stories, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

FLC The First and Second Lady Chatterley Novels, eds. Dieter Mehl and Christa Jansohn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Fox The Fox, The Captain’s Doll, The Ladybird, ed. Dieter Mehl (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

FWL The First ‘Women in Love’, eds. John Worthen and Lindeth Vasey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

IR Introductions and Reviews, eds. N. H. Reeve and John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

K Kangaroo, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

LAH Love Among the Haystacks and Other Stories, ed. John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

LCL Lady Chatterley’s Lover and A Propos of ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’, ed. Michael Squires (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

LEA Late Essays and Articles, ed. James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

LG The Lost Girl, ed. John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

MEH Movements in European History, ed. Philip Crumpton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

MM Mornings in Mexico and Other Essays, ed. Virginia Crosswhite Hyde (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

MN Mr Noon, ed. Lindeth Vasey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984).

PFU Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Plays The Plays, eds. Hans-Wilhelm Schwarze and John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

PM Paul Morel, ed. Helen Baron (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

PO The Prussian Officer and Other Stories, ed. John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

1Poems, 2 Poems D. H. Lawrence: The Poems, Volumes I and II. Ed. Christopher Pollnitz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

3Poems D. H. Lawrence: The Poems, Volume III Uncollected Poems and Early Versions. Ed. Christopher Pollnitz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

PS The Plumed Serpent, ed. L. D. Clark (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

Q Quetzalcoatl, ed. N. H. Reeve (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Paintings The Paintings of D. H. Lawrence (London: Mandrake Press, 1929).

R The Rainbow, ed. Mark Kinkead-Weekes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

RDP Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays, ed. Michael Herbert (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

SCAL Studies in Classic American Literature, eds. Ezra Greenspan, Lindeth Vasey and John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

SEP Sketches of Etruscan Places and Other Italian Essays, ed. Simonetta de Filippis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

SL Sons and Lovers, eds. Helen Baron and Carl Baron (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

SM St. Mawr and Other Stories, ed. Brian Finney (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

SS Sea and Sardinia, ed. Mara Kalnins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

STH Study of Thomas Hardy and Other Essays, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

T The Trespasser, ed. Elizabeth Mansfield (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

TI Twilight in Italy and Other Essays, ed. Paul Eggert (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

VicG The Vicar’s Garden and Other Stories, ed. N. H. Reeve (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

VG The Virgin and the Gipsy and Other Stories, eds. Michael Herbert, Bethan Jones and Lindeth Vasey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

WL Women in Love, eds. David Farmer, Lindeth Vasey and John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987).

WP The White Peacock, ed. Andrew Robertson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

WWRA The Woman Who Rode Away and Other Stories, eds. Dieter Mehl and Christa Jansohn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).