Yesterday evening a rally in Guildhall Square, Derry, marked the end of a three-day march by more than 160 walkers over the 70 miles from Belfast. The marchers’ slogan was ‘Failure is not an option’, presumably with regard to the Good Friday Accords, and the precious, fragile peace which has held in Northern Ireland since they were signed in 1998. The proximate cause of the march was the accidental murder of twenty-nine year old journalist Lyra McKee in Derry on 18thApril 2019 – five weeks ago – apparently by a member of the New IRA. McKee had been observing the violence that had broken out between that group and the police in the Creggan estate, in the wake of police raids to confiscate munitions.

Less than a month before this event, I had visited Derry, and Northern Ireland, for the first time. This visit revolutionised my attitude towards, and knowledge of, Ireland. I had previously viewed its nationalism with much sympathy, considering it to have historical right on its side – but also with some of the distance that one imbibes from James Joyce. My inner compass points Eastwards, to the giant landmass of Europe and Asia with their millions of people and myriad peoples; I have never been drawn Westwards, to the Celtic fringe, where I rather feared that I might drop off into the Atlantic. About loyalism I understood very little. I knew that there was something in the English metropolitan barely-veiled contempt for the Ulster Unionism that it was happy to exploit, that troubled me. It seemed to border on an ‘acceptable’ form of anti-Irish racism, with many of the same elements as old anti-Catholic prejudice, but the fear replaced by condescension. Yet I knew little about it, or about its part of the UK. I did not know, for example, that you do not go through passport control when flying from London to Belfast, and how connected this makes an English visitor feel. Or, conversely, that the money is privately printed by the region’s various banks, and how foreign this makes an English visitor feel.

I did not know whether Belfast airport gift shops would market Ireland, or Northern Ireland. It turned out that it was both, sometimes side-by-side.

Nor had I – distrusting as I did the condescending metropolitan rhetoric about Northern Ireland – anticipated the extent to which visiting it would feel like travel back in time, but in wholly positive ways. Everyone whom my husband and I met was not just polite, but friendly; not just friendly, but polite. Prices were about half those in London. Our Derry hotel served nostalgically-familiar brands, such as Corn Flakes, but not new-fangled entities, such as croissants. I wasn’t initially entirely clear about where Northern Ireland stood, latitudinally, in relation to Britain. I had subconsciously considered all of Ireland roughly on a level with Wales, for all the thousands of times I had looked at – but not seen – maps of the British Isles. An excursion to Fort Grianan made apparent how much like Northern England the country looks and feels; Derry being on a latitude with Newcastle makes sense of this. Grianan (pronounced ‘Greenan’) is an Iron Age fort just across the invisible border to Donegal and the Republic of Ireland, a short taxi ride from the city which, geographically, should have become part of the Republic, but which the British for symbolic reasons were particularly eager to keep. The sheep safely grazing on each side of this eccentrically-drawn border very clearly had nothing to do with international politics; they graze the grass on the one side; they graze the grass on the other. Both Republicans and Unionists in Northern Ireland are majority Remainers; Derry, which is c. 75% Republican and 25% Unionist, voted 76% Remain in the 2016 – the highest of anywhere in the UK. The reactivation of the old customs house as part of a hard border is unthinkable. I was told that people would rebel against any attempt to impose it.

The Good Friday Accords were signed over two decades ago, but the peace which they brought still felt valued and slightly conditional. On both sides wounds remained painful. In two days I didn’t see a single policeman, but there were many signs that the city had comparatively recently been a warzone.

I was shown round Bogside (the Catholic estate where the Bloody Sunday massacre was perpetrated in 1972) by a formerly-imprisoned member of Sinn Fein. I learned that the city walls, built early in the seventeenth century by James I, were used by British Army to fire on the march in the extramural Catholic settlement below, in a continuance of their original purpose. In fact the Bloody Sunday march was not narrowly a Republican, but a civil rights, march, and included some Protestants. Until 1973, property-ownership and rate-paying were requirements for suffrage in local elections. Protestants were favoured in getting jobs; relatively few Catholics owned property, and so the latter were relatively disenfranchised – but the poorer in both groups were affected. After the massacre, recruitment to the IRA rose sharply, and the civil rights marches became still more inflamed. The city-side (the side nearest to the Walls) border of Bogside has now been transformed into a memorial site.

Here are the names of those killed on Bloody Sunday:

And these – on an H-shaped monument in memory of H-block at the Maze Prison (until 1976 Long Kesh) – are the names of the hunger strikers who died 1981-2, and the number of days for which they survived without food. Many were young. Their actions cost the British government much sympathy, including in England itself – and, in the long run, were not in vain.

And this is a surviving gable of a building near which several people were shot in 1972. ‘Free Derry’ (Londonderry remains its official name, as is apparent on municipal signs, such as at the station) has been designated as the sole slogan to appear on this wall; other messages, however sympathetic, are regularly whited out.

In general, however, I was impressed by the intersectionality (to use a concept du jour) of Republicanism. The ‘Free Derry’ mural was inspired by a protest at Berkeley University. Palestinian prisoners made statements of sympathy with the IRA hunger strikers, and vice versa. The Palestinian flag covers the gable of the free Derry Museum. Derry is – remarkably for someone living in London – a place where you can openly express sympathy for Palestine, and nobody would call you anti-Semitic.

Conversely, Unionists sometimes express common cause with Israel (as violently besieged by a surrounding ethnic majority). The Free Derry Museum, which commemorates the Troubles, and Bloody Sunday in particular, was established two years ago. A museum, I realised, places that which it represents firmly – safely – in the past. Or it does it best to do so.

In Derry cemetery – beautifully situated above the river Doyle – graves of killed IRA members are marked by flagpoles which fly Irish flags on the anniversary of the Easter Rising of 1916. I asked where Protestants are buried, and was told that this was not formally a sectarian cemetery; but my informant could not tell me whether unionist fallen are similarly marked by flagpoles.

Epitomising Derry’s radical-progressive edge is Sandino’s bar, covered in liberation movement memorabilia – up to and including this table of photographs of the other RAF, the Rote Armee Faktion.

For 105 days in 1689, the Williamite forces within the Derry walls were besieged by Jacobite forces. Visible from those walls today is this mural, which refers to that siege, and belongs to one of the remaining Unionist housing estates.

The exhibition on the history of the Ulster Plantation, from the sixteenth century to the present, in Derry Town Hall, was admirably informative, open, and non-sectarian – a difficult line to tread.

I attended a reception with Derry’s Deputy Mayor, who, according to the current power-sharing agreement, is Ulster Unionist. He movingly shared the grounds for his strong unionism (the friends and former pupils murdered during the Troubles), the fact that poor Protestants such as his own family were also disenfranchised prior to 1973 – and he heard contrasting views with consideration and respect. It helped that both he and the man who had organized this reception (and the event for which I had travelled to Derry) turned out to be Brexiteers. An amused sense of common feeling made itself felt over the polished table and the tea. This, I thought, is what peace looks, feels and smells like.

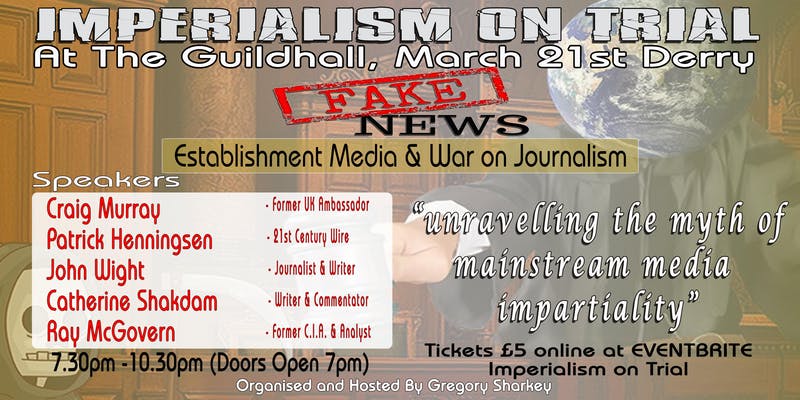

The event, which was held in Derry Town Hall, was entitled ‘Imperialism on Trial’, and was addressed, amongst other speakers, by the former UK Ambassador to Uzbekistan Craig Murray, and the former senior CIA analyst (and deliverer of daily CIA briefings to Presidents Kennedy, Nixon, and Bush Sr) – now chairman of Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity – Ray McGovern.

Patrick Henningsen made the point that war (aka ‘intervention’) does not command majority support in many Western countries, and that Bush Jr., Obama and Trump all ran on anti-intervention platforms and won the US Presidency.

Craig Murray talked about how the Overton Window (of acceptable discourse) has narrowed, and moved to the right, over his lifetime. He asked: ‘when did the BBC last interview someone who is against the UK possessing nuclear weapons?’ And he made the point that, though his political views have scarcely changed over his lifetime, as a young man he identified as centre-right; now he finds himself classified as hard left. He also quoted William Gladstone’s speech against the fourth Afghan war: ‘if they resist would you not do the same’, and made the point that no politician today would dare to make such a point as he made.

Ray McGovern shared this defence of Julian Assange, since when he has not been invited back onto CNN.

I have since asked the organizer of this event, Greg Sharkey, what he thought of the recent resurgence of his native city’s ‘Troubles’. He said that the big difference was that this time, he and others felt free to rebuke the perpetrators on social media. Before that, he said, they would have felt too intimidated to do so. The recent peace march is indicative of the same confidence, as is the fact that the sister of the murdered journalist has reached out to the killer, offering to help him/her deal with his/her sense of guilt.

I am profoundly glad that I went to Northern Ireland. Partly for the excellent event, which stepped beyond the Irish anti-imperialist cause to a critique of modern American foreign policy internationally. But also because, in all of two days, my attitudes towards both sides in Northern Irish politics were transformed. I came back with greater sympathy for all who live there, and a much greater sense of the responsibility that the UK government bears to do all it can to support – and all it can to avoid hurting (through a hard border or otherwise) – the peace for which last weekend’s marchers marched.