The following article was commissioned by IAI (Institute of Arts and Ideas), and published March 15th 2019; the following is a pre-edited version. This may be considered a companion piece to my blog post ‘What is Good Sex Writing?’.

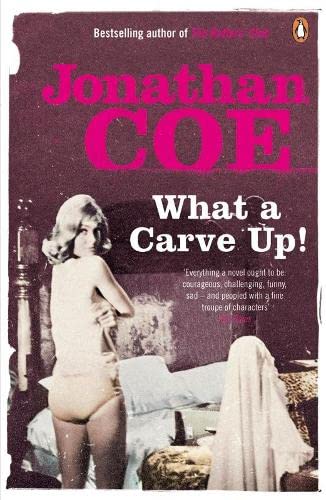

In Jonathan Coe’s 1992 anti-Thatcherite satire, What a Carve Up!, the Tory tabloid journalist Hilary Winshaw publishes a novel that boasts ‘Sex every forty pages’. By the standards set by EL James twenty years later, that is paltry. Ever since the 1960s, British publishers have been pressurising their authors to write sex in order to boost sales, presumably following the success of the novel that inaugurated that decade, the unexpurgated Lady Chatterley’s Lover. By 1993,the British literary magazine Literary Review felt the need to create the ‘Bad Sex Awards’ in order ‘to draw attention to the crude, tasteless, often perfunctory use of redundant passages of sexual description in the modern novel, and to discourage it.’ Winners have included Melvyn Bragg 1993, Sebastian Faulks, 1998, Tom Wolfe 2004, Norman Mailer 2007, Ben Okri 2014, and, most recently, James Frey in 2018.

At the risk of taking too-seriously an award of which the keynote is not seriousness, there are several problems involved in this that are worth considering. One is the implicit hypocrisy that the award has brought great publicity to its parent magazine because of the very fact – which the award ostensibly disparages – that sex sells. Indeed especially badly-written sex sells, hence the success of the Fifty Shades trilogy (‘I detonate around him, again and again, round and round, screaming loudly as my orgasm rips me apart, scorching through me like a wildfire, consuming everything.’ [Fifty Shades Freed]).

Then there is the fact that – since individuals’ sexual experiences are nothing if not mutually varied – one person’s literary bad sex may be another’s actually-quite-moving sex. The format of the awards ceremony itself – in which actors read out the short-listed passages, to reliable laughter from their audience – militates against any other reaction than ridicule. Yet I have on several occasions at these ceremonies found myself laughing with my face only.

Then there is the ambiguity of the adjective. What is meant by ‘bad’, we infer, is ‘aesthetically poor’. But it is striking that ‘bad sex’ – in the sense of the spectrum that covers disengaged sex, through unenjoyable sex, to coercive sex and rape – is relatively little featured in the shortlists. A scene containing rape is, by a common delicacy in the use of language, less likely to be described as a ‘sex scene’ than as a ‘rape scene’; therefore ‘bad sex’, as far as the awards are concerned, often means ‘rather good sex’. Pornography – in the sense of literature in which sex predominates – is formally excluded from the awards, but it is also marginalised from them in the sense in which DH Lawrence redefined the term in his 1926 essay ‘Pornography and Obscenity’:‘even I would censor genuine pornography, rigorously […] you can recognize it by the insult it offers, invariably, to sex, and to the human spirit. Pornography is the attempt to insult sex, to do dirt on it. This is unpardonable.’

Lawrence’s own sex scenes have been the more ridiculed the ‘better’ they have been, which is why Lady Chatterley’s Lover– of which an early draft title was Tenderness– has been so widely parodied. Mervyn Griffith-Jones, Chief Prosecutor at the novel’s trial, held this passage up to ridicule: “‘Beauty! What beauty! A sudden little flame of new awareness went through her. […] The unspeakable beauty to the touch of the warm, living buttocks! The life within life, the sheer warm, potent loveliness. And the strange weight of the balls between his legs!’ Griffith-Jones is held up to history’s perpetual mockery as the man who asked his jury: ‘Is it a book you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?’ But in other parts of his prosecution, the world has laughed with rather than at him, and parodies of the novel (such as the 1960 Lady Loverley’s Chatter) have been numerous. The world does not similarly laugh at ‘bad’ sex in Lawrence, such as Gerald’s consummation of his relationship with Gudrun in Women in Love: ‘He found in her an infinite relief. Into her he poured all his pent-up darkness and corrosive death, and he was whole again. […] And she, subject, received him as a vessel filled with his bitter potion of death. She had no power at this crisis to resist. The terrible frictional violence of death filled her […] But Gudrun lay wide awake, destroyed into perfect consciousness.’

Alienation – which is not sex itself – rescues such passages from ridicule. This points to the fact that the Bad Sex Awards have what is intrinsically an easy target. Looked at from the outside, the physical actions of sex, and mental concentration involved in them, often seem absurd – as any pre-pubescent finds when ‘the facts of life’ are explained to them (why would Mummy and Daddy want to do that?), and as Lady Chatterley finds during her one instance of alienated sex with Mellors, when ‘her spirit seemed to look onfrom the top of her head, and the butting of his haunches seemedridiculous to her, and the sort of anxiety of his penis to come to itslittle evacuating crisis seemed farcical.’

This is the more acutely the case when one comes to sex cold, as at an awards ceremony, when graphic descriptions of sex blast out of nowhere into polite conversation, excised from the novels to which they belong. Yet to some extent this effect pertains even within the novels themselves. Thus literature mimics life – at least, life as understood as not being all about sex. As DH Lawrence wrote contra Freud in 1922: ‘All is not sex. And a sexual motive is notto be attributed to all human activities.’ And so one moves through one’s day, relatively unaroused. Then, suddenly, there it is. Its dominance can throw one off one’s professionalism, one’s dignity, one’s time-keeping, one’s ethics, and one’s readerly or narrative stride. Sex scenes can interrupt rudely, and can lower the dignity of a novel.

Unless the novel is comic, in which case it will embrace the ridiculousness of sex as viewed externally. Howard Jacobson’s 1983 debut novel Coming From Behind opens with Professor Sefton Goldberg having sex with a mature student on the floor of his office, thinking of nothing but the fact that he cannot remember whether or not he locked the door, and wishing that he might develop the faculty of sight out of his anus, which is currently facing that door. It is not sex, but anxiety, that is being described, and the reader’s laughter is safely channelled against the character and with the author rather than against them both. If a character is fully involved in sex, and if the narrative is not distanced from them, then it is safer to fade to black, as James Joyce does at the famous ending of Ulysses: ‘I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.’

When one tries to infer from the Bad Sex Awards shortlists what makes sex writing particularly bad, one finds oneself listing a series of mutually-contradictory qualities.

Characters’ concentration on sex risks bathos, yet their distraction from it risks the same: ‘She became aware of places in her that could only have been concealed there by a god with a sense of humour’ (Ben Okri). Metaphors are dangerous because they obtrude the extraneous into the intrinsically unmediated. They are either the objective correlative of highly-subjective emotion recollected by the author in tranquillity, or are shots in the dark in an attempt to move or arouse others. For a majority of actual readers, they will fail: ‘Her vaginal ratchet moved in concertina-like waves, slowly chugging my organ as a boa constrictor swallows its prey. Soon I was locked in, balls deep, ready to be ground down by the enamelled pepper mill within her’ (Major Victor Cornwall and Major Arthur St John Trevelyan).

Yet if inventive descriptions are bathetic, so are clichés: ‘Somewhere in the night a stray rocket went off’ (Okri). So too is straightforward description: ‘Moves up to kiss her strong nose, on one side, then the other […] He moves back down, till he is level with her breasts’ (Julian Gough). There is nothing ridiculous about either kissing a woman’s strong nose, or moving level with her breasts, but factual sex writing, as much as the imaginative, tends to produce in the reader that state of alienation to which all intimacy is ridiculous.

Attempts to overcome this by describing the subjectivity of someone who is involved in sexual experience tend not to work either – Joyce’s Molly Bloom being an honourable exception. Last year’s winner, Katerinaby James Frey, is no such exception:

‘I’m hard and deep inside her fucking her on the bathroom sink her tight little black dress still on her thong on the floor my pants at my knees our eyes locked, our hearts and souls and bodies locked.

Cum inside me.

Cum inside me.

Cum inside me.’

In Connect (Julian Gough) we read:

‘He kisses them. Teases a nipple with his lips. It’s so soft; and then, suddenly, hard.

Wow’

The final exclamation recalls the ejaculations of Anastasia’s consciousness that punctuate the Fifty Shades trilogy (‘Holy crap!’, ‘Holy shit!’, ‘Holy Moses!’) Yet in such situations, one does not think words – and that is where literature, intrinsically, has a problem.

Evasive language, such as ‘her pleasure cave’ (Major Victor Cornwall and Major Arthur St John Trevelyan), and taboo language, such as ‘Cum’ (James Frey passim), fare as badly as each other with Bad Sex Awards audiences. DH Lawrence deliberately made his gamekeeper use four-letter words, in order to purge them – like sex itself – of their association with dirt. But in this he failed utterly. It was pointed out by Griffith-Jonesthat: ‘the word “fuck” or “fucking” occurs [in Lady Chatterley’s Lover] no less than thirty times. I have added them up, but I do not guarantee to have added them all up. “Cunt” fourteen times; “balls” thirteen times; “shit” and “arse” six times apiece; “cock” four times; “piss: three times, and so on.’ More than half a century later, Jed Mercurio, the writer-director with whom I worked on the latest, 2016 BBC1 adaptation of the novel, told me that at the BBC ‘Currently fuck is strongly discouraged and cunt is unacceptable. They count number of uses and proximity to programme start. Every use of fuck would have to be approved at Controller level’. Because these words remain as dirty as ever, their use in literature still feels contrived, aggressive, or naïve.

Michael Owen – novelist-protagonist of What a Carve Up! – discovers just how difficult it is to write sex when, on his editor’s advice, he sits down and tries to do so. He starts by writing a long list of words connected to sex, and then, when this fails, cracks open a bottle of wine and tries to go for spontaneity. He desperately rotates alternative settings, clothes and adverbs. Finally he thinks:

‘Oh, to hell with it.

she was panting with desire

he was bursting from his pants

she was wet between the thighs

he was wet between the ears

she was just about to come

he didn’t know whether he was coming or going’

Coe knows what the problems are – but he also finds a solution. What a Carve Up! contains the single most beautiful literary description of sex I have read. Michael Owen does not write it in his capacity as a novelist; rather, he transcribes his dream of being in bed with the girl he loved as a child, Susan Clement:

‘the first thing I knew – almost fainting with the joy of it, the mazing, palpable reality – was that she was touching me, that I was touching her, that we were dovetailed, entangled, coiled like dreamy snakes. It seems that every part of my body was being touched by every part of her body, that from now on the entire world was to be apprehended only through touch, so that in the musty warmth of my bed, the curtained darkness of my bedroom, we could not but find ourselves starting to writhe gently, every movement, every tiny adjustment creating new waves of pleasure, until finally we were rocking back and forth, cradle-like, and then I couldn’t stand it any longer and had to stop.’

What this passage manages to do is to tread a number of very fine lines. It is both literal and metaphoric, physical and imaginative, as sex itself is; it is a ‘dream’ of ‘mazing, palpable reality’. It animates dead metaphors such as ‘dovetailed’ alongside cooperative live metaphors such as ‘snakes’. It connects physical delimitation (the ‘curtained darkness of my bedroom’) with the ‘entire world’. It allows the separateness of ‘I’ and ‘she’ whilst also uniting them as ‘we’. It points to sex’s possible outcome (the ‘cradle’). And it is reverent towards an experience that cannot be long supported, and is humble in its acknowledgment of the need for it to come to a stop. Sex cannot take up a whole life, nor a whole novel. But passages such as this demonstrate that it is possible for language to render the joy of sex, even if it so much more easily conveys its failures and its ugliness. The Good Sex Awards – showcasing examples such as this, however controversial they might prove – could provide a better service to writers, readers, and sexual beings than the existing Bad Sex Awards.

I hereby propose as the first Chair of the Judges, Jonathan Coe; and let the prize itself be named for D.H. Lawrence.