To own a Penguin 1960 copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover is to own a piece of history – a copy of the book which aimed to end dirty books, of which the unbanning led to the publication of a slew of dirty books. (I’m not convinced that, given the consequences of Penguin’s victory, Lawrence wouldn’t rather have had his novel remain as it was, circulated in private and foreign parts).

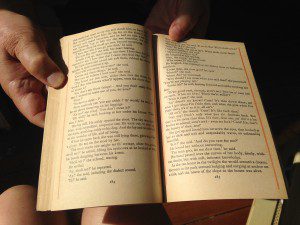

But to own a prosecutor’s copy of the Penguin 16th August (pre-trial) 1960 edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover is to own a particularly eloquent piece of history. I don’t. A friend, who used to know someone who worked in for the Crown Prosecution Office, does. He was kind enough to let me handle it. Here are a few pages:

I photographed these at random from among those marked by the Prosecution in coloured pencil as grounds for their case. There are many such.

In the first double-page (56-57 in the Penguin August 1960 edition; 53-55 in the Cambridge University Press edition edited by Michael Squires, 1993), Michaelis and Connie have sex. He comes first, and then – eventually – she. He complains about this, at which their relationship ends.

In the second double-page (130-31 in Penguin; 125-27 in CUP) Mellors rubs his face over Connie’s thighs and belly. They have sex, from which she feels disconnected: ‘surely that thrusting of the man’s buttocks was supremely ridiculous. Surely the man was intensely ridiculous in this posture and this act!’ (126 CUP). Afterwards he helps her up and out of his hut.

In the third double-page (184-5 in Penguin; 176-78 in CUP) Connie and Mellors, having had sex, talk about having children, about when and where they will next meet, and about the meaning of the word ‘cunt’, with which Connie is unfamiliar. Mellors tells her: ‘It’s thee down theer; an’ what I get when I’m i’side thee – an’ what tha gets when I’m i’side thee – it’s a’ as it is – all on’t!’ The chapter ends: ‘As she ran home in the twilight, the world seemed a dream; the trees in the park seemed bulging and surging at anchor on a tide, and the heave of the slope to the house was alive’ (178 CUP).

A few observations occur.

The passages highlighted are not in their entirety ‘obscene’, as the prosecution was interpreting the Obscene Publications Act 1959. They contain, as described above, considerable stretches of conversation, including on non-sexual topics. The prosecution is, therefore, considering descriptions, and the bluntest descriptors, of sexual acts, in their context. Whole scenes are highlighted, perhaps in the spirit of the censor (or Secker and Frieda, who made the first authorised expurgated edition after Lawrence’s death), who wishes to render the novel not-obscene, but still functional as a novel.

But herein lies the rub. Context was all. The Obscene Publications Act 1959 required that the most sexual scenes and words in the novel be read not just in local context, but in the context of the whole novel. This was how US Federal Judge Frederick Bryan read them, when making his judgment that the novel was not-obscene in the preceding year: ‘These passages and this language understandably will shock the sensitive-minded. Be that as it may, these passages are relevant to the plot and to the development of the characters and their lives as Lawrence unfolds them. The language which shocks, except in a rare instance or two, is not inconsistent with character, situation and theme.’

On the first day of the London trial Gerald Gardiner pointed out the difficulty of removing sections without altering the whole: ‘You see, members of the jury, my learned friend or anybody else can take a blue pencil. There are, of course, passages in Hamlet to which the Cromwellian Puritans strongly objected. You could cut them out, but ten you would not only have to cut out those bits, but you would have to cut out subsequent bits which, though not objectionable themselves, relate back to the first bits; probably you would find it necessary to write in a certain amount and at the end of the day the play would not be the Hamlet which Shakespeare wrote.’

On the fifth day he told the jury: ‘You must take the book as a whole. Another thing you must do is this: you must not regard yourselves as a board of censors with bue pencil in hand, saying to yourselves, “Well, I don’t think it is very desirable that that piece should be put in and I think we will cut out that piece.” You are not acting as a board of censors. You are deciding whether it has been proved that the offence of publishing an obscene publication has been committed.’

When the literary critic Richard Hoggart was called as a Defence witness he wrote of the four-letter words that: ‘the first effect, when I first read it was some shock, because they don’t go into polite literature normally. Then as one read further on one found the words lost that shock. They were being progressively purified as they were used. We have no word in English for this act which is not either a long abstraction or an evasive euphemism, and we are constantly running away from it, or dissolving into dots, at a passage like that.’

Lawrence himself certainly felt the book to be an organic whole. When it was suggested to him that he expurgate the novel himself, he wrote: ‘I might as well try to clip my own nose into shape with scissors. The book bleeds.’

And yet, the ‘broken spine’ with which copies of the novel are associated indicates that, with a certain kind of supporter, the book too gets mutilated, as its sex scenes are highlit in a spirit of approval rather than the reverse.

Secondly, Hoggart’s claim that the novel’s taboo words are ‘progressively purifed’ does not apply to most of the novel’s readers. This progression was not, apparently, felt by the red-and-blue-pencilled prosecutors, nor by those spine-breaking fans whom these words thrilled to the end. Where the novel has failed with its readers it has failed with society – to clean these words, and sex itself, of their association with dirt. For which reasons screen adaptations of Lady Chatterley’s Lover (such as that forthcoming from BBC1 in autumn 2015) cannot use those words which Lawrence and Mellors saught to clean. As for the BBC restrictions on sex and nudity: of these I am confident that Lawrence himself would have approved. He would have the paying of actors paid to be naked as a form of prostitution, and a degradation of sex by voyeurism.

Thirdly, I cannot, in the sections photographed above, or elsewhere in the book, work out any method in the use of blue as opposed to red pencil (the only two colours used). Further study might reveal one, but as I only had access to the book for a few minutes, I have instead glanced at how these colours operate in the novel itself.

Blue – the traditional colour of the censor’s pencil – is also the colour of the novel’s eyes: Clifford’s (‘pale blue’), Connie’s (‘dark blue’), Mellors’s (‘wicked blue’), Connie’s father’s (‘big blue’), and even those of Daniele the Venetian boatman (‘long-distance blue’). I think that our prosecutor’s pencil is none of these; nor is it that of the ‘bright blue’ of the bluebells in which Clifford’s motor-chair gets stuck. Rather, it is the ‘dark blue, with crystalline, turquoise rim’ of the sky above Connie and Mellors after one of their unions in the hut.

The red of the red pencil, on the other hand, is not the red of Clifford’s angry face, nor that which Mellors sees when he is with ‘a Lesbian woman’, nor of the Bolshevists whom, in the final draft of the novel, Mellors does not quite join, nor of the ‘bright scarlet’ trousers which Mellors desiderates that men would start wearing, nor the ‘hard and dark red’ of Mellors’s moustache – but the ‘bright red-gold’ of his pubic hair, which Connie finds ‘the loveliest of all!’.

My final thought is that, especially in the third photo above, you can see some context. My friend – a retired English schoolteacher who now teaches at City Lit – came round on a warm summer’s day. His hands hold the book open to me. I, sunny-legged, read from it. The book looms out of the darkness as a bright book of life.