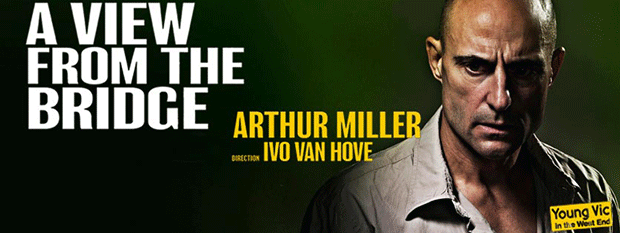

Wyndham’s Theatre, West End, transferred from the Young Vic where it played in 2014; running until 11th April 2015.

Director – Ivo Van Hove

Eddie – Mark Strong

Catherine – Phoebe Fox

Beatrice – Nicola Walker

A view from the bridge indeed. My seat was part way up an on-stage rake. Like the wealthy New Yorkers who would look down from Brooklyn Bridge at the eponymous view of the working-class district in which the play is set – of the same city, but not of the same world – I looked down on the tragedy – of the same stage, but not of its action.

This was palpable despite the fact that the set shunned the naturalism so carefully stage-directed by Miller. There was no attempt to recreate any of the physical sensations of life among semi-legal Sicilian port workers in 1950s Brooklyn (gratifying if occasional moments of male toplessness aside). Instead, the set was a perspex-rimmed box placed stage-centre, recalling the boxing-ring set of the Young Vic’s recent play about office bullying, Bull. Its modernism belonged to the intelligentsia of the play’s time and of our own, but its minimalism provided also a stage for universality.

Yet the play’s numerous, vigorously co-existent themes are of varying levels of universality. The English play which premiered in the same year, and was a still greater hit than it in London – John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger – was recognised as articulating a resentment which typified the country’s recently-state-educated, working-class, angry young manhood. A View from the Bridge was also of its time and place – the same New York as A West Side Story, which came out in the following year. Here, a more traditional Sicilian, and a more modern American, culture meet and clash.

But A View from the Bridge is also more broadly about honour, heterosexual lust (it was written in the year in which Miller married Monroe), homosexuality, incest, girls becoming women, or failing to, or not being allowed to – and the law’s impotence to protect people from some of the greatest harms they can experience (limits recently loosened in the UK by the criminalisation of emotional domestic violence). Eddie Carbone’s incredulity when the play’s narrator-lawyer explains to him that the law offers him no way to stop his seventeen-year-old ward and niece marrying the man she wants, is both touching in its naivety and moving in its emotional sense. Catherine means far more to him than his property, which he has in any case invested largely in her. Yet the law which would protect the slightest part of that property can do nothing to stop someone from taking the person who means more than anything else to him.

The acting was excellent, as attested at a distance of five metres. The soundtrack, pulsing louder and quieter throughout, was Fauré’s 1888 Requiem. This worked – because it is moving, beautiful, and presages death. But its loving, optimistic Catholicism finds no echo in the play’s Catholic Sicilians, nor in their Grecian tragedy (Sicily remembers Ancient Athens as well as Christian Rome). The play’s climax, reached after two hours without an interval in what was one of the best pieces of staging I have ever seen – the cast gridlocked in love and hate under a rainstorm of blood – is no Dies Irae (Fauré’s Requiem contains none), but a massacre caused entirely by men. The narrator-lawyer Alfieri’s final ruminations on the destroyed protagonist do not imagine him in eternal rest (or torment), but rather reflect, with Grecian philosophy, on what had been his great qualities, and his hamartia.

Throughout the play I was reminded of the half-year which I spent in New York. I was hanging out with a Sicilian waiter who worked in the Lower East Side, but lived in Brooklyn, in an estate of wooden houses many of which had Madonna statues outside. He told me not just of his aspirations to climb within the New York Sicilian restaurant trade (aka the mafia), but about the small town in Northern Sicily which he had left behind. At his Aunt’s house in Queens I saw photos of this town. Its hundreds of New York immigrants had set up a Castellammare del Golfo Society, where they could meet to feel Sicilian, as well as American. Soon thereafter, 9th September 2001 hit New York’s restaurant trade hard, and destroyed his hopes of staying in America. He returned – as the play’s Marco had intended to – to Sicily, where I could not imagine myself into the role of his wife. I could not, I felt sure, survive in an honour culture.